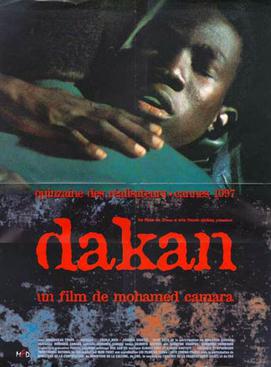

DAKAN

DAKAN

Directed by Mohamed Camara

Released July 7, 1997

While Dakan made waves as the first openly West African queer love story, its significance extends far beyond its historic debut. Released in 1997 and directed by Guinea-born filmmaker Mohamed Camara, Dakan is widely recognized as a trailblazer for African queer cinema. The film not only depicts the romantic relationship between two men, Sory and Manga, but also challenges the societal norms of Guinea and defies conventional expectations of African storytelling in film. In many ways, Dakan presents a unique narrative that continues to resonate with audiences over two decades later.

However, the true power of Dakan lies not just in its groundbreaking subject matter, but in the fact that it was told by someone who shares a deep understanding of the cultural context it portrays. The story serves as a compelling reminder of why it is crucial for queer African filmmakers, and African filmmakers in general, to tell their own stories. Authentic representation is vital, as only those who have lived the experiences portrayed on screen can truly capture their depth and nuance. When queer African stories are told by outsiders, there is a huge risk of misrepresentation, and as a result, the richness of the experience can be lost. This is why directors like Mohamed Camara, who approach the story from a place of empathy, awareness, and love, are essential in creating films that are not only authentic but also deeply impactful.

Dakan—meaning “destiny” in Mandingo—premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1997. Unapologetic in its exploration of queer love, Dakan defied not only the societal norms of Guinea at the time, but also the expectations placed upon African storytelling in film. Set against the vibrant backdrop of Guinea, Dakan tells the coming-of-age tale of Sory and Manga, two high school boys navigating their love amidst societal opposition. From the opening scene—a high-angle shot capturing the two sharing an intimate kiss in a red convertible at night—the film signals a break from traditional narratives. The scene is accompanied by Sory Kandia Kouyaté’s “Toutou Diarra,” a classic Mande song that evokes the spirit of precolonial West Africa. This pairing of homoerotic imagery with an anthem of cultural pride boldly carves out a space for queer love in Africa, a groundbreaking move that shocked and captivated audiences.

For Camara, Dakan was an intensely personal project, despite the challenges he faced in bringing it to life. As the film’s ‘subversive’ theme led the Guinean government to withdraw financial support, Camara continued to face many difficulties. Casting actors became nearly impossible, with Camara’s own brother stepping in to play Manga, and Camara himself taking on the role of Sory’s father. Yet, Camara’s resilience and persistence were unwavering. In his words, “I made this film to pay tribute to those who express their love in whatever way they feel it, despite society’s efforts to repress it.” Through Dakan, on screen and off, he honored the courage of those who defy societal constraints to stay true to their hearts.

Djibril Diop Mambéty, a revered figure in African cinema, famously walked out of the Cannes press conference for Dakan, declaring to Camara, “You can be sure that your career is over, but in a hundred years, people will still talk about you.” This statement, both a warning and an acknowledgment of the film’s daring nature, highlights Dakan’s polarizing impact. In many Western countries, narratives involving queer Black and African characters often reinforce stereotypes, framing queer lives solely around homophobia or sexual encounters. Dakan, however, avoids these tropes by offering a nuanced, empathetic portrayal of two young men simply in love. There’s no sensationalism; instead, Sory and Manga wear their love openly, unapologetically, without seeking acceptance or validation.

Camara’s choice to focus on the universal theme of love over conflict allows Dakan to transcend boundaries. The protagonists aren’t tragic figures wrestling with internalized homophobia, nor are they depicted solely through the lens of societal disapproval. Instead, Sory and Manga are complex individuals who find joy and solace in each other, even as the world around them fails to understand their connection. This approach renders the film timeless, a reminder that queer lives encompass far more than suffering and oppression.

In the film’s most striking moments, the cinematography—a tapestry of raw, saturated hues—feels ahead of its time, almost reminiscent of Moonlight’s visual language. The blue and yellow tones cast across the night scenes create an aesthetic that speaks to the beauty of queer existence. Through this intentional lighting, Camara captures the vulnerability and intensity of young love, framing it within a landscape that feels simultaneously dreamlike and realistic.

As a trailblazer in African cinema, Dakan serves as a reminder that stories of queer resilience and identity remain essential, especially in societies where expressing one’s true self is still met with hostility. Despite its initial reception, Dakan carved out a space for African queer narratives, laying the groundwork for a new generation of filmmakers to tell their own stories. In an Africa where many countries continue to criminalize homosexuality, Dakan stands as a testament to love’s defiance against repression. Until the day arrives when queer individuals can live freely and safely across all regions, films like Dakan will continue to hold immense significance, inspiring conversations about acceptance, love, and the right to exist authentically.

Francis Buseko is a creative director, photographer, designer and writer with a passion for uncovering untold stories. Their work spans both visual and written storytelling, exploring queer narratives, Black experiences, and unearthing cultural gems. Francis’ work has been published in The Quietus, Afropunk, Office Magazine, Voyagers Journal, HUF Magazine, and PAP Magazine. They excel at connecting the past to the future through a multidisciplinary approach to storytelling. You can follow them on Twitter and read more of their work on Tumblr.

Francis Buseko is a creative director, photographer, designer and writer with a passion for uncovering untold stories. Their work spans both visual and written storytelling, exploring queer narratives, Black experiences, and unearthing cultural gems. Francis’ work has been published in The Quietus, Afropunk, Office Magazine, Voyagers Journal, HUF Magazine, and PAP Magazine. They excel at connecting the past to the future through a multidisciplinary approach to storytelling. You can follow them on Twitter and read more of their work on Tumblr.