“Mehretu’s art is invested in our lived experiences, and examines how forces such as migration, capitalism, and climate change impact human populations—and possibilities,” The Whitney’s website notes. Loosely chronological, Mehretu, who is a mixed Black queer woman, shares pieces from 1996 of paper drawings, sketches, and small paintings from her days in graduate school at Rhode Island School of Design to her most recent painting, Ghosthymn (after the Raft), a 12-foot by 15-foot canvas overlooking the Hudson.

Her sketches, such as Character Migration Analysis Index and Timeline Analysis of Character Behavior— both ink on mylar from 1997— inform the development of her worldbuilding, particularly when it comes to storytelling through her art. From dots, circles, and arrows, to more intricate taxonomy designs like wings, breasts, and eyeballs, Mehretu established early on in her career the foundation of her style that continues to permeate her future works as they complicate along with the world’s complexities.

In 1970, Julie Mehretu was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Other places of residency throughout her life included East Lansing, MI, as well as Harlem and Berlin. Artistry aside, as a person whose upbringing involved multiple migrations through the world, maps “make sense of who I am in my time and space and political environment,” she regards in the exhibition. At the crux of maps and her personal voyages, Mehretu’s art denotes what happens when the two meet: maps, given context by history and travel, evolve into visual stories. Arrow taxonomies can become families, lines can become directions, colors can become current events. These narrative modules built to be the abstraction she’s known to do.

The first painting of the exhibit looms opposite of the elevators when stepping out. The piece is Transcending: The New International of 2003. Its museum label provides context for the mid-career survey exhibition as a whole, including a quote from French philosopher Édouard Glissant (1928-2011) that reads, in English: “We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone.” In Glissant’s perspective, those who are marginalized have an expectation to be transparent in order to make those with more power understand them clearer. Glissant then argues people should have a right to remain unassimilated, pigmented, and opaque: a double entendre on Mehretu’s political values as well as her artistry.

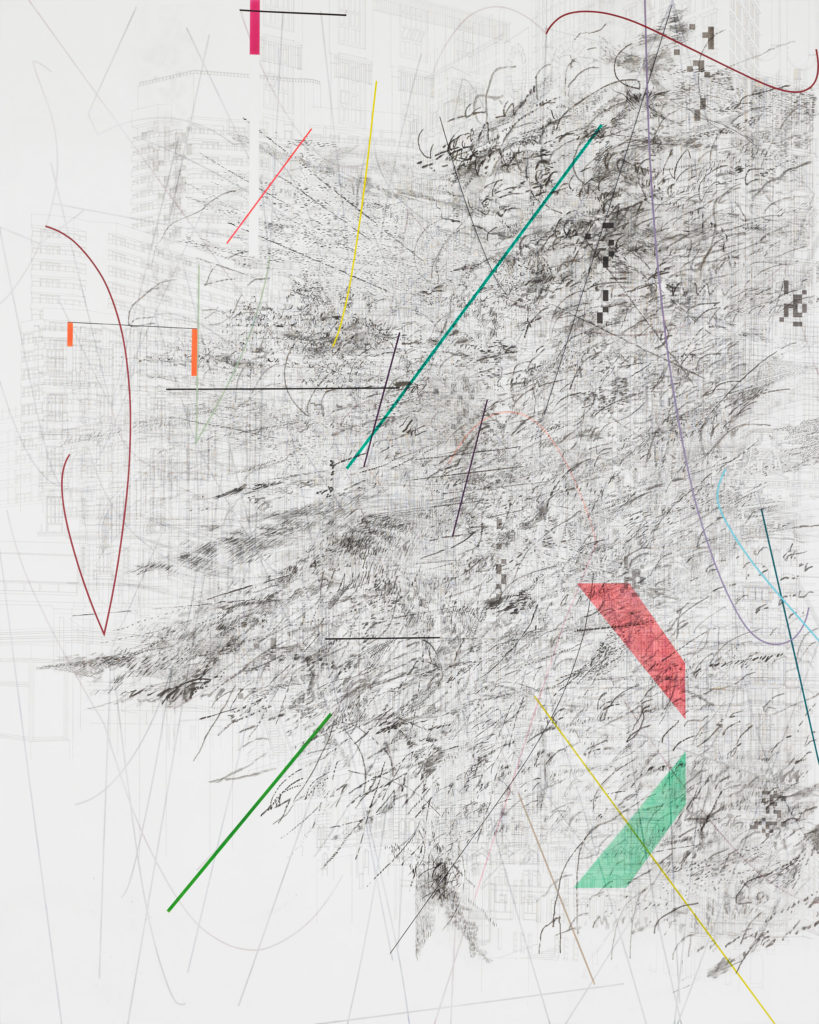

“Layering” would be the simplest way to describe Julie Mehretu’s work. Having established her own style in the 2000s, she starts with line drawings of architecture. She would spray or add a layer of acrylic to create a sheen surface. Then, the next layer could be colors, taped off images, masking. Over and over, the layers get sanded down in between each application so the surface remains flat. Therefore, it builds depth without physically becoming multi-dimensional or thick.

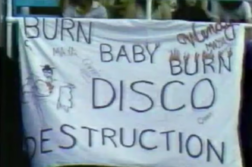

Her design inspirations derive partially from utopianism, clear in the brutalist architectural designs deep within her initial sketch layers. The Whitney’s assistant curator Hockley calls this “the promise of a future” that is double-sided. One hand holds the promise of creation, but the question “for whom?” provides context for collateral damage, especially when it comes to the visions of the world, where simultaneous construction and destruction occur in very real ways. Sometimes in direct link to each other.

In the exhibition, her work shifts in 2009 (while she was a fellow at the Guggenheim), wherein her work remains to be explosive via lines and movement, only with a transition into grayscale. Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts), inspired by the Arab Spring uprising, was done in 2012, and was initially made for an installation in Kassel, Germany. The paintings were also shown at White Cube in London, and finally at The Whitney for this exhibition. Even the paintings themselves move across the world.

Mehretu’s most recent works have evolved; the foundational layers of her paintings come from manipulated real photographed images—adding a new essence to her work. Images include the 2017 Women’s March in D.C. following Drumpf’s election, as well as the Muslim ban protests in airports around the country.

The final gallery displays Ghosthymn (after the Raft), which Mehretu started in 2019 and finished specifically for this exhibition — the only venue to display this painting. The source of the background images includes the anti-immigration demonstrations in Dresden in 2020. Ghosthymn looks over the Hudson river, done intentionally to interact with the view outside of the museum. Southward out the window, the Statue of Liberty is in view, a potent stance on immigration that, with the statue’s symbol in mind, is not new. Contrary to today’s rhetoric around immigration, migration, at the very core, has shaped the world’s history since its inception. For Ghosthymn to face the Hudson river reminds us of the history at the heart of what we know as American civilization: colonialism and immigration.

From the notational systems of her character designs to her printmaking, Mehretu has developed her work as means of conveying moments of implosive and explosive world events. But Mehretu’s shifting developmental style is not periodic; they gradually shift. An entire floor at The Whitney is a major feat, and even then an entire floor cannot be encyclopedic for an artist’s journey—especially for work over the course of 25 years. Curators Kim and Hockley selected pieces they could see as “moments” that were emblematic in Mehretu’s work. Mehretu herself also had a major part in curating her pieces.

Although press and news regarding the exhibition honor Mehretu’s mid-career survey exhibition, online commentators of various articles voice their personal critiques. “I feel like she is the one percent of artists,” a commenter says. “Her fame allows her to have several assistants […] I do not see how artists can say they are for social change and be so invested in inequality in the arts.”

Where, then, does irony lie in Mehretu’s work? Does it lie in between the vast layers of her paintings? Does it hide in the empty wall spaces between each work across the fifth floor of the Whitney?

“Her work is very good and highly processed [with the help of her assistants],” another commenter says. “Nothing wrong [with that—it’s]been happening since the renaissance, but sometimes it just feels too programmed to the moment.”

Acknowledging the audience’s pessimistic comments is not to critique Julie Mehretu’s rigor and work—it is clear she has made and will continue to make her mark in the art world. But how does her resonance to Édouard Glissant’s “right to opacity” uphold when her final piece lies in front of a transparent window? To observe and be observed all at once?

A writer, actor, and musician, Denny (yes, like the breakfast diner!) is a digital kid who made a home on the internet. Creator of Decoding Ellipses on Tumblr, she is a recent graduate of the Master of Arts in Public Media program at Fordham University.