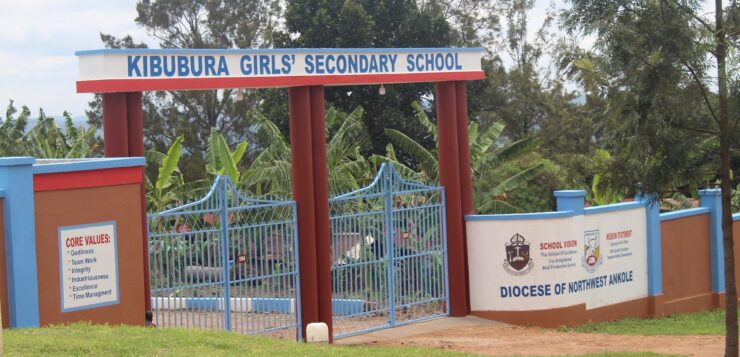

Pregnancy checkups at my boarding school in Western Uganda were often conducted halfway into each three-month semester. As we lined up in front of the sickbay waiting our turn on the nurse’s examination table, it was obvious who was worried (perhaps they’d had a little too much fun with their boyfriends during the school break). Our school, Kibubura Girls, was affiliated with Mbarara High—nicknamed Chapa—the all-boys boarding school on the other side of the district. It was considered cool to date a guy who went to Chapa. The pairing was sanctioned by Kibuchapa, a portmanteau like ‘Brangelina.’

I didn’t have a boyfriend, so pregnancy checks didn’t bother me. Indeed, they were an opportunity to do the lord’s work; I was omulokole, a saved person. I was drawn to the girls on whose faces I read concern, preaching to them about purity.

“Sister,” I often began, “do you know what happened when Eve allowed the serpent to tempt her to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil?”

Many of them were already annoyed with me. “Read the room, Iryn.”

But I was nothing if not persistent. “If all goes well here today,” I’d say, “Let’s have tea. Just to talk.”

In addition to being a hardcore omulokole, I was also the head girl, the highest student leadership position. It meant that I had a residence of my own called State House—with a bedroom and sitting area—tucked at the end of Ibadan, the A’ level dormitory block. Being in a position of authority whilst also a leading member of the school’s largest club, Scripture Union, made me one of the most visible students.

For the most part, the students with whom I had tea in State House sought spiritual guidance. I remember helping a new convert write a long letter to her boyfriend at Chapa. We wanted him to understand that things were going to be different going forward. When they next saw each other, there would be no smooching or anything of the sort. This wasn’t necessarily a breakup, mind you. He was welcome to receive salvation—there was a Scripture Union at Chapa, too— which would allow their relationship to continue, albeit in a platonic way, until they got married.

Occasionally, a student or two was expelled following a pregnancy check-up. More often than not, everyone was safe.

My school was equally vigilant about weeding out lesbian students. Every dormitory had a Dorm Mother, a female teacher who lived in the staff quarters just beyond the fence. Dorm Mothers conducted impromptu middle-of-the-night inspections. If a girl wasn’t in her bed at the time of inspection, they’d have a lot of explaining to do. There were snitches who ratted out fellow students they caught being lovey-dovey with each other.

A few of the saved girls who visited me in State House were struggling with their sexuality. “Coming out” wasn’t in our vocabulary at the time, but I suppose that’s what they did. They came out to me in the hopes that I might offer some guidance on how to deal with this “burdensome” part of themselves which, if discovered, would cause them severe punishment both at school and everywhere in the country.

Uganda’s ban on homosexuality stretches back to the Penal Code Act of 1950, a British colonial penal law which criminalized same sex sexual relations as ‘carnal knowledge against the order of nature.’ At school, we were taught that lesbianism was unnatural and offended God, who created us in his own image.

“God allows the enemy to test us,” I told those girls, repeating verbatim my mum’s response the year before when I had confessed my bisexuality to her. “It’s how he refines us so that we may enter his kingdom.”

I’m not even sure I believed those words myself. My mum had died not long after I came out to her, and my grief was so big it was eroding both my psyche and my faith. I doubted God’s munificence. Did I really want to spend my afterlife with a god I was beginning to perceive as petty and vindictive?

In 2009, two years after I moved to Canada, Ugandan parliamentarian David Bahati introduced the Anti-Homosexuality Bill (AHB). The bill built on sections of that old colonial law to include new offences related to the practice and support of homosexuality. Now, if you knew someone gay and didn’t report them to the authorities, you were, in effect, supporting their criminality. The bill also introduced a new category, ‘aggravated homosexuality,’ aimed at same sex relations where one of the involved parties was HIV-positive, a minor, had a disability, or was in a position of authority relative to ‘the victim.’ In this case the proposed punishment was death, so media called the AHB “Kill the Gays.”

Before crafting his horrendous bill, Bahati—along with several politicians and members of the clergy—had attended a seminar in the capital, Kampala. Titled “Exposing the Truth Behind Homosexuality and the Homosexual Agenda,” the massive multi-day seminar was led by three visiting American evangelical Christian pastors: Holocaust revisionist Scott Lively, the self-described ex-gay man; Caleb Lee Brundidge, a “sexual reorientation coach” for the International Healing Foundation; and Dan Schmierer, a member of the ex-gay group Exodus International. News reports said these men expressed outrage that Ugandan leaders weren’t doing more to stop the spread of the idea that LGBTQ rights were human rights. After the seminar, Lively met privately with a group of lawmakers and government officials, including Bahati who would, a few months later, present a draft of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill to parliament.

For four years the AHB stalled in parliament while it was being discussed in cabinet sub-committees. Local activist groups and human rights organizations challenged the bill in the courts of law. Several donors, including the World Bank, signaled that they’d cut off aid if the bill was passed.

But in 2014, President Yoweri Museveni went ahead and signed the AHB into law: The Anti Homosexuality Act. Fortunately, the AHA was quickly nullified over a technicality: it had been passed by a parliamentary sitting that lacked the requisite quorum. Still, homosexuality had always been criminalized, thanks to colonial-era laws. Yet now the issue was more prominently on the minds of Ugandans and the entire news-reading world. Meanwhile, police ramped up their crackdowns, using familiar jargon to justify new brutalities. If they raided a gay-friendly bar and arrested everyone inside, they charged those patrons with being ‘a public nuisance’ or something with similarly vague phraseology. There was a rise in extortions and catfishing schemes targeting LGBTQ folks, driving many into exile. Some fled across the border to Kenya. But without the necessary papers to legally work in that country, many queer refugees resorted to sex work under unsafe conditions.

Despite the efforts of activists and petitioners, Museveni, in 2024, passed the Anti-homosexuality Act once again (with minor amendments removing sections about reporting homosexual acts, and infecting someone with a ‘terminal illness’ through gay sex). This time the constitutional court upheld the draconian law while also acknowledging it violated key human rights, including the rights to health and privacy.

I feel fortunate to be living in Canada where I get to enjoy the rights and freedoms made possible by the gay liberation movement. It upsets me to think about how Canada and Uganda were both colonized by Britain, and how Uganda which, long after the political colonial project ended, continued and continues to criminalize homosexuality. Even more infuriating is the fact that the regressive anti-gay legislation was influenced, and continues to be fueled, by evangelists and anti-LGBTQ groups from the global West. White saviours are continuing the work started by the early missionaries and colonialists who viewed Africans as savages. Those agents of the Church Missionary Society set fire to our beliefs. They literally built huge bonfires where natives were encouraged to burn the charms and idols that connected them to their traditional religions, which were then replaced with Christianity. And now, ironically, modern day missionaries have convinced Ugandans that homosexuality is imported from the West when, in fact, homophobia is the import.

When I look back to my secondary school days, I regret not coming out to my queer sisters. Certainly, it made me feel less depressed knowing there were others in my school like me. I’m sure it would have helped them in return to know that their proselytizing head girl was queer, too. That they were not alone.

Iryn Tushabe is an Ugandan-Canadian writer and journalist. Most recently her nonfiction has appeared in The Walrus and in the trace press anthology river in an ocean: essays on translation. Her short fiction has twice been included in The Journey Prize Stories: The Best of Canada’s New Writers. She was a finalist for the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2021, and a 2023 winner of the Writers’ Trust McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize. Everything is Fine Here (House of Anansi April 22, 2025) is her debut novel.