Within a period of a week, two seemingly unrelated articles were published that speak directly to the ideas I’m about to present. The first, in HIV-Plus magazine, was a dialogue between me, a 56-year-old-cisgender gay white man, and Cole Hayes, a 26-year-old trans man, discussing the challenges associated with the uptake of PrEP. The second was an exposé by Jesse Green in The New York Times Style Magazine examining the evolution of gay plays, many of them centering on AIDS, in light of the 2018 rebooting of Mart Crowley’s Boys in the Band. Both of these entries into the gay annals speak to the ideas that became so abundantly clear in my musings about the development of gay identity over the fifty years since the Stonewall Riots—namely that, while much has changed, much of what it means to be a gay man and the struggle to be a gay man continues to the present time.

These stories specifically speak to one unconditional, unwavering, and unrelenting reality that has cut across the decades. Since the momentous events that took place at a small bar in Greenwich Village from June 28th to July 1st, 1969, three generations have emerged into adulthood—cohorts of gay men that I have come to know as: 1) the Stonewall Generation that came of age in the 1960 and ’70s, prior to and around the time of the Riots; 2) the AIDS Generation that emerged into adulthood in the 1980’s-90’s at the height of the AIDS crisis; and 3) the Queer Generation that navigated adolescence and young adulthood in the post-9/11 years and following the economic crash of 2008-’09. While each of these generations came of age in different eras and in different social, political, and economic contexts in the U.S., each has come to terms with the reality AIDS.

It has been said by some of my own generation—those in the middle cohort—that AIDS is a disease that has defined our lives. And while the epidemiological data certainly suggest that the disease is most prevalent among those who were born between 1960 and 1964 (IAS 2015: 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and PreventionVancouver, Canada18-22 July 2015), no gay man born a decade or two earlier or any time since has been untouched. I take umbrage with those gay men of my generation—of whom there are many—who point their fingers in disbelief and disgust at younger gay men who continue to become infected.

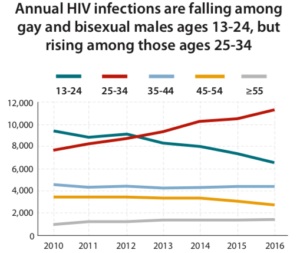

The statistics for HIV reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are sobering. More  than half (57%) of people with diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV in the U.S. are gay and bisexual men, and at least two-thirds of all new HIV infections each year are gay. While estimates put the population of gay men at about four percent of men in the U.S., the rate of new HIV diagnoses is more than 44 times greater. Since the beginning of the epidemic, more than 325,000 gay and bisexual men with AIDS have died.

than half (57%) of people with diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV in the U.S. are gay and bisexual men, and at least two-thirds of all new HIV infections each year are gay. While estimates put the population of gay men at about four percent of men in the U.S., the rate of new HIV diagnoses is more than 44 times greater. Since the beginning of the epidemic, more than 325,000 gay and bisexual men with AIDS have died.

My experience and that of my generation is not unique. While biomedical advances in the form of PrEP and PEP (post exposure prophylaxis) offer a glimmer of hope in containing the disease, the bottom line is that AIDS continues to bombard gay men because of the marginalization and stigma that’s perpetrated by the larger society. These are the social conditions that have made us especially vulnerable to AIDS and numerous other health burdens, such as drug addiction, depression, and violence, as well as the ignorance of the medical profession regarding our unique health needs.

While the police may not be arresting us as they did in the 1960s, and while evangelical Christians may not be celebrating AIDS as the wrath of God as they were in the ’80s, we are still subjected to the vitriol of haters, many in positions of authority. Consider how the Trump administration weaponizes religious freedom to permit healthcare providers not to treat us (see Sean Cahill’s “Executive branch actions promoting religious refusal threaten LGBT health care access,” Fenway Institute), echoing the early days of AIDS when gay men were abandoned by many in the medical profession, despite the oath they took. Yet Trump also heralds the end of AIDS by 2030 through the widespread use of these pharmaceutical advances, failing to understand that HIV is as much a social as it is a viral phenomenon. The actions of his Administration to undermine the rights of the LGBTQ population could overwhelm progress in medications designed to end the epidemic.

There is no doubt that social and political conditions are much improved since the historic events of 1969. But if the deteriorating social conditions for LGBTQ people created by the current Administration persist in the U.S. and around the world, the AIDS epidemic, which has transcended time and space, will continue to impact generations of gay men around the world for decades to come.

Perry N. Halkitis is Dean, Professor, and the Director of the Center for Health, Identity Behavior & Prevention Studies (CHIBPS), School of Public Health, Rutgers University. His book Out in Time: From Stonewall to Queer, How Gay Men Came of Age Across the Generations was published by Oxford University Press in June 2019. For more info about him, visit his website.

Perry N. Halkitis is Dean, Professor, and the Director of the Center for Health, Identity Behavior & Prevention Studies (CHIBPS), School of Public Health, Rutgers University. His book Out in Time: From Stonewall to Queer, How Gay Men Came of Age Across the Generations was published by Oxford University Press in June 2019. For more info about him, visit his website.