Often the word “outlier” is used in cancer treatment to describe a patient who beats the odds and lives longer than expected. Those outliers celebrate their status. But an outlier can also refer to someone whose response to treatment is not consistent with the bell curve of a normal distribution. I was diagnosed in 2020 with cancer of the tongue and lymph nodes. I underwent a brutal surgery, losing more than half of my tongue. This was followed by 33 targeted radiation treatments that left me a shell of my former self.

Oncologists told me that normally someone regains their ability to swallow, taste food, and return to much of their former quality of life. This has not happened to me. I cannot swallow any food that requires chewing. My taste buds have never returned. And I still have sores in my mouth that have never fully healed from the radiation treatments. I am an outlier.

I want to complain about being an outlier, but the minute I begin to form the words, I catch myself. You see, I have been an outlier before. And then, I had no complaints.

In 1985, I tested HIV positive. With no treatments available then, AIDS patients were moving from first symptoms to death in months. I could have been one of them. But in 2024, I am a long-term survivor of AIDS who has been infected for 41 years and counting. All of the statistical modeling would have predicted that by now I would probably have succumbed to this disease. But I am still here, still active, despite what the statistics might have predicted. I know so many gay men who tested positive like me and died a long time ago, some long before they ever could even celebrate a thirtieth birthday. I will turn 69 this year and, have enjoyed many bonus years, and for that, I am truly grateful. I am an outlier.

Gay men are used to being outliers. Many on the political right claim the “gay agenda” dominates and therefore must be pushed back on. Even now, some worry about the threat of a right-dominated Supreme Court, not shy about upending Roe v. Wade, overturning Obergefell v. Hodges.

But given my cancer and my AIDS diagnoses, I must embrace my outlier status.

I don’t think you can logically complain about being an outlier for one illness and yet welcome that status for another. Chronic disease may not predispose us toward consistency in our thinking, but that’s where I find myself. While I hate drinking my nutrition daily (a smoothie mixed with fruit, vegetables, and protein) that I cannot taste, I have to recognize that my being an AIDS outlier means I am still around to walk through my Florida neighborhood, marveling at a family of ducks traversing my street, or parrots squawking above me in the trees. A butterfly floats from bloom to bloom on my patio, and I am here to watch it dance in the sunshine as the wind whistles in the palm trees outside my window.

Imagine no longer being able to eat solid food. It’s hard. Eating is such a big part of every culture. Not being able to swallow food or taste anything is a major drawback. Drinking a daily smoothie is like filling the gas tank, something you have to do. But it’s hard for me to keep drinking for more than five minutes. I try to recite a poem between gulps to make it last a few beats longer. “The Garden of Proserpine” by Charles Swinburne is a favorite:

From too much love of living

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives for ever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.

To keep socially involved, I signed up with a nonprofit agency to teach an English conversation class for refugees over Zoom. Most of my students are women from Syria and Afghanistan. Many are nursing newborns and do not turn on their cameras, which makes understanding their speech a challenge.

For me, coping with my health challenges has meant crafting a narrative about my life where I am not simply a victim of my disease. Illness beats us down. We reach a point where we think we cannot manage another setback. This pummeling may invite a passive stance, that we lack control over what happens to us due to the vagaries of our illness and the specific medical care available to us. But I think that is a mistake. Passivity can be a killer. Taking a more proactive approach to how I recount what has happened to me and my role in making it less of a burden is vital. This has been achieved though meditation, through finding a reason to laugh daily, through continually finding ways to help others, through accepting that we have always known that death is part of our human story.

I still marvel that I was the beneficiary of the surgeon’s skilled work. In a feat of medical engineering, the surgeon took nerves from my left arm and reconstructed a new tongue. How miraculous is that? That we live at a time when such operations are possible. But, of course, there is a downside to all of this. Forming words with the new tongue is a challenge and my speech is slow and slurred. This teaches me a certain humility when people hear my slow words and assume that I am mentally deficient. Quite a come-down for a man who used to give poetry readings in his young adulthood.

Yes, it hurts to be sick. We can adopt a mental framework that puts our situation in a larger context where normal distributions may be routine for statisticians, but being an outlier has its own special quality: nuanced, complicated, but one where there are still joys to savor and pains to transcend.

I am an AIDS outlier. I am a cancer outlier. And therein lies the foundation of adopting an approach built on living in the present moment, on making today count since we have no idea if tomorrow will even be something we get to see. And that’s okay because enjoying the “now” is full of all sorts of beauty in nature and music and colors and laughter. … If we are paying attention.

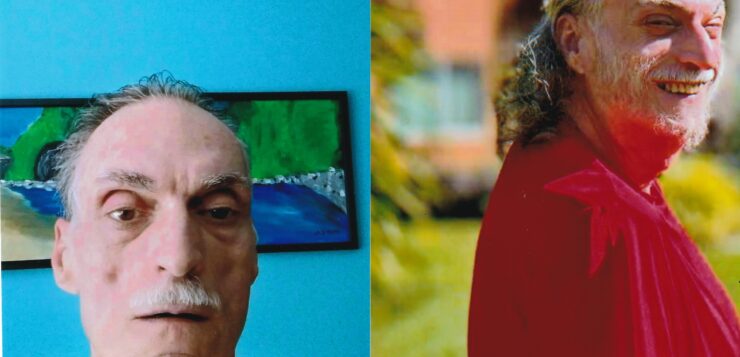

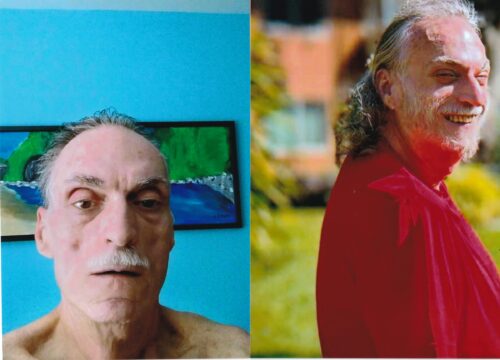

Michael Varga is a retired Foreign Service Officer and author of the novel, Under Chad’s Spell. He was diagnosed with AIDS in the 1980s and with cancer in 2020. Read more of his work at www.michaelvarga.com

Michael Varga is a retired Foreign Service Officer and author of the novel, Under Chad’s Spell. He was diagnosed with AIDS in the 1980s and with cancer in 2020. Read more of his work at www.michaelvarga.com