The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore

Directed by Augustin Correro

Tennessee Williams Theatre

Company of New Orleans

Sweet Bird of Youth

Directed by Mel Cook

Southern Rep Theatre

“At Liberty”

A performed reading

Directed by Paul J. Willis

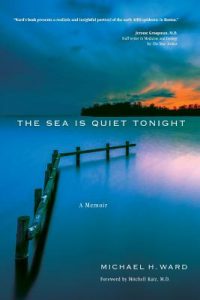

The Sea Is Quiet Tonight

The Sea Is Quiet Tonight

by Michael Ward

Querelle Press. 190 pages, $19.99

OUR FIRST NIGHT in New Orleans at Saints & Sinners—the gay literature festival that will celebrate its fifteenth anniversary next year—my friends and I drive out to Loyola University to see a production of Sweet Bird of Youth by the Southern Rep Theatre. (Because Saints & Sinners now runs concurrently with the Tennessee Williams Festival, not only are there productions of his work at various venues around town which do not cost an arm and a leg, but your Saints & Sinners badge gets you into some of the Tennessee Williams panels as well.) The next morning we gather at the Beauregard-Keyes House to see a one-act by Williams that I’ve never even heard of. “At Liberty” is about a showgirl who comes back to a miserable small town in Mississippi to live with her mother. She’s being suffocated by having to return home less than a star, plus whatever it is that’s causing a cough that periodically interrupts her monologues.

The cough reminds me immediately of The Ridiculous Theater Company’s Charles Ludlam in his parody Camille. But then, there’s a fine line between camp and tragedy in much of Williams’ work. (One story has him sitting in the back of the theater at a performance of A Streetcar Named Desire helplessly laughing as Blanche is dragged off to the asylum.) The dying heroine, the lady who coughs, is part of a romantic tradition that goes back to Alexandre Dumas’ The Lady of the Camellias. So, after the performance, when the festival’s artistic director Augustin Correro gives us a lecture on Tennessee Williams’ career and life, it makes sense to be reminded that his first published short story, “The Vengeance of Nitocris,” was about a pharaoh’s sister who drowns her brother’s enemies en masse in a banquet hall and then commits suicide. In other words, the attraction to the gothic, the doomed, the death theme, was there from the very beginning.

What strikes one about Sweet Bird of Youth, however, is how sexual it is. The first scene is really about locking oneself up in a hotel room with a hustler to take drugs and screw. The actress Alexandra del Lago, aka the Princess Kosmonopolis, is on the run from what she fears is another flop, but there’s still plenty of fight and sexual desire left in her. Indeed, when she famously says, “When monster meets monster, one has to give way,” you know who it’s going to be. It’s the women in Tennessee Williams who embody the life force—from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to Sweet Bird of Youth to even a one-act like “At Liberty”—though in a play that I see two nights later, The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, produced by The Tennessee Williams Theatre Company of New Orleans, that life force is nearly spent. Flora Goforth is dying; indeed, it’s announced at the beginning of the play by the kabuki-like attendants that these will be the last two days of her life. In Sweet Bird the heroine merely needs a portable supply of oxygen to still her panic attacks; in Milk Train she needs a lot more—and she doesn’t get it. When she has fits of coughing and removes the handkerchief from her mouth, it’s stained with blood.

Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore

The death of Flora Goforth is so bleak, so comfortless and solitary, that it’s a shock when Thomas Keith, a panelist at both festivals who knows more about Williams than anyone I know, tells me that Williams worked on Milk Train more or less concurrently with Sweet Bird, between 1959 and 1961. And since Williams did not die until 1983, at the age of 72, that means he lived for more than twenty years with this vision of what he must have suspected would be his own fate, to wit, the embattled panic of Alexandra del Lago and the loneliness and sexual deprivation of Mrs. Goforth.

That Williams could create two such different heroines, at different stages of life—one still full of fire, the other doomed—is remarkable. In Sweet Bird, he lets the Princess have sex with the handsome hustler; in Milk Train the beautiful young man who has climbed the hill on which Mrs. Goforth’s villa sits won’t even give her a kiss. Nor is the latter woman easy to admire. She’s paranoid, greedy, vain about her body, and trying to hold on to everything Death is about to take away. She’s a hag (which is why Elizabeth Taylor, never more beautiful, was so miscast in Boom!, the infamous film version of the play, as was Richard Burton, too middle-aged to be the sex object that a young man named Levi Hood played to perfection in New Orleans). If Flora is a projection of Williams himself, the fact that he lived for so many years after depicting her extinction gives new weight to the psychodrama portrayed by John Lahr in his 2014 biography, whose subtitle was “Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh.”