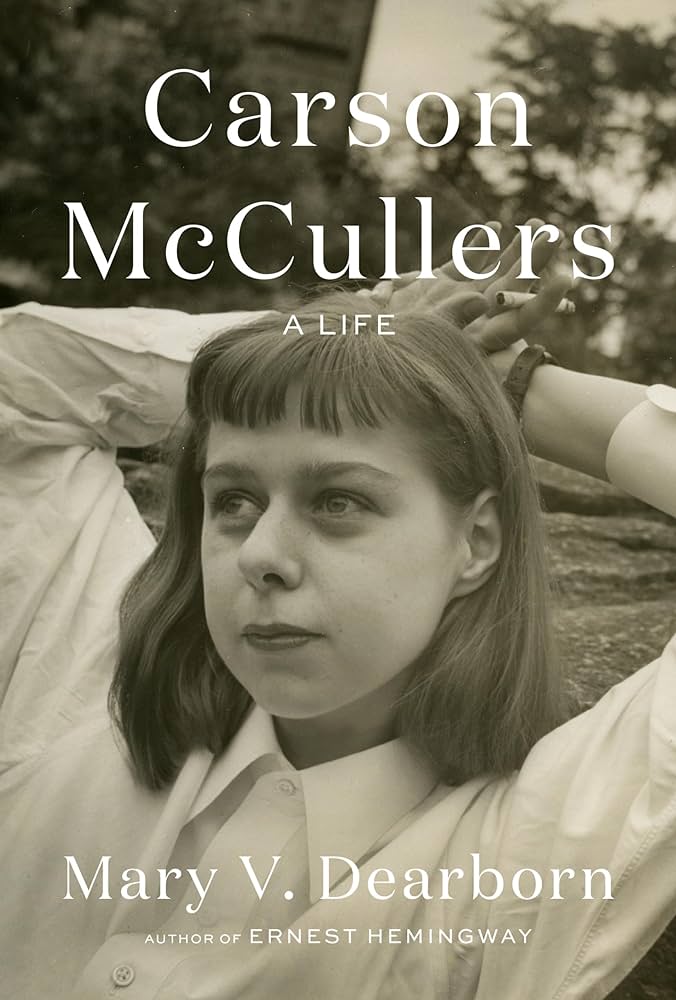

CARSON McCULLERS: A Life

CARSON McCULLERS: A Life

by Mary V. Dearborn

Knopf. 496 pages, $40.

THE MEMORABLE TITLES were not hers: The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter was suggested by an editor at Houghton Mifflin. (Her working title was “The Mute.”) And Reflections in a Golden Eye was a phrase taken from a T. S. Eliot poem (her title was “Army Post”). But the haunting quality of the prose was pure Carson McCullers.

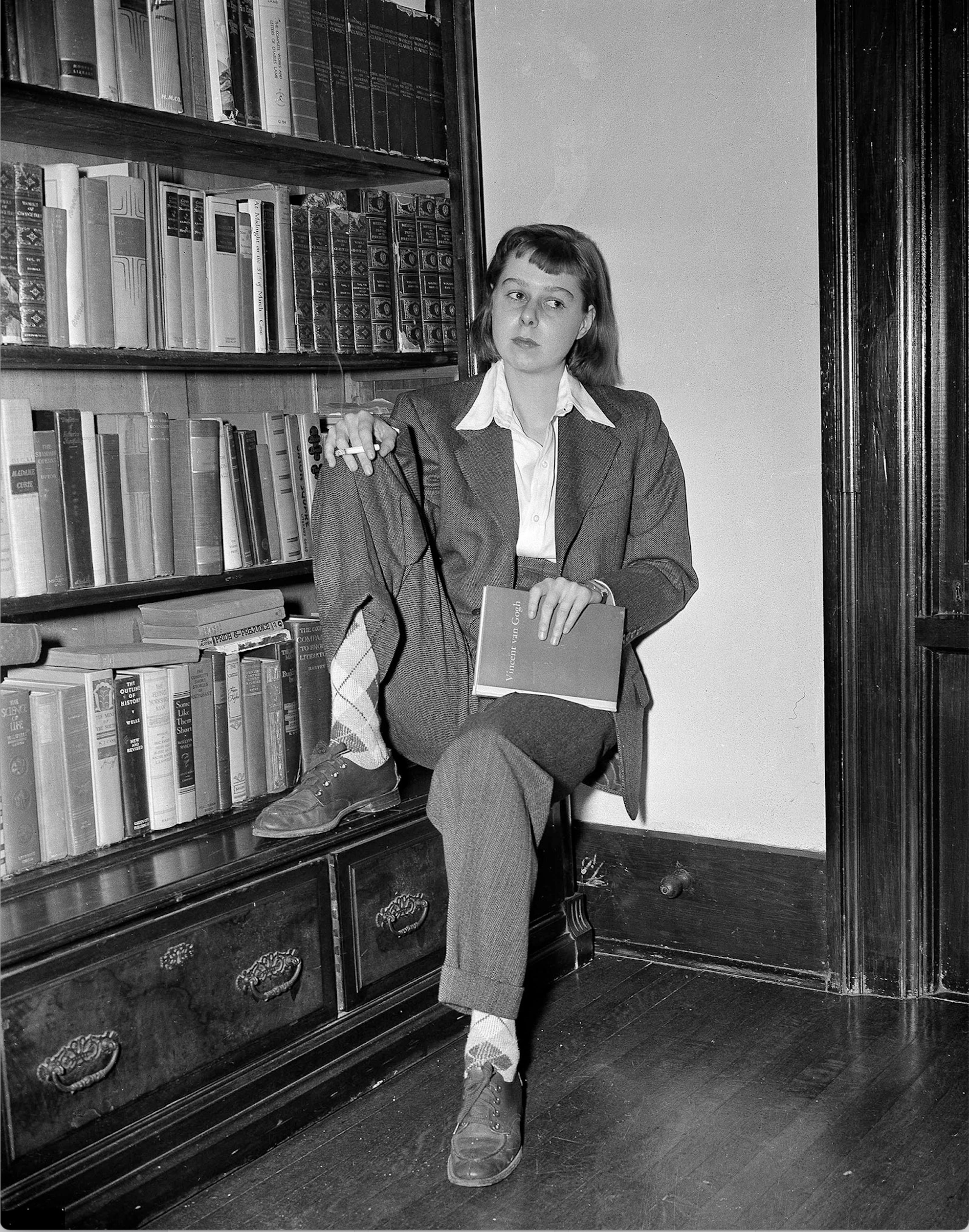

She belonged to that generation of Southern writers whose work dealt with a topic that, as Mary Dearborn points out in the first new biography of McCullers in two decades, had previously been confined to pulp fiction in the U.S. She herself played up her own androgyny. The photograph that Louise Dahl-Wolfe took for Vogue of the young Carson McCullers after the success of The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter was part of her mystique. Dressed in a crisp white man’s shirt and jacket, she was hard to place. Tall, gawky, with shadows under her eyes, her prominent nose and receding chin were not conventionally pretty. The portrait reminds one of the photo on the back of Other Voices, Other Rooms of Truman Capote lounging on a couch while looking at the camera with an expression so disturbing that it could stand for Southern Gothic, which is what both he and McCullers exemplified.

Like her rival Capote and dear friend Tennessee Williams, McCullers wrote about outsiders. The main character in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter is a deaf mute whose beloved friend is also mute. In The Ballad of the Sad Café, a masculine woman falls in love with a dwarf. In Reflections in a Golden Eye, a homosexual Army officer becomes obsessed with a handsome soldier he sees riding naked on a horse on their Army base. Another officer’s wife finds companionship in her effeminate Filipino houseboy and later cuts off her nipples with garden shears. The word “lesbian” was never spoken aloud in the South of McCullers’ day, Dearborn says, but it was the very fact of the subject’s being taboo that enabled McCullers to write about outsiders like these. Homosexuality was the secret, the taboo, that informed much of Southern Gothic.

The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter was a literary sensation. Critics were amazed that a 23-year-old writer could have produced such a deep and mature work. It was followed by Reflections in a Golden Eye, and then a volume of short stories that included her most famous tale, “A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud.” From the start, she was considered a type that she had referred to in the title of another story in that book: a “Wunderkind.”

Georgia, 1941. Courtesy AP Images.

Her family knew she had gifts from the start, especially her arts-loving mother, whose unconditional love gave McCullers a confidence that she wouldn’t lose for the rest of her life, and, paradoxically, a hunger for a love that she did not experience until late in the game. Her mother presided over the sort of home that people visited if they wanted to talk about books, listen to music, and drink—in a town that McCullers wanted to ditch for New York as soon as she could.

The first woman McCullers fell in love with was her piano teacher—the wife of the commanding officer of Fort Benning, an Army base near her hometown. Her musical abilities led the family to assume that McCullers was on her way to a career as a classical pianist, and not the writer that she abandoned her musical training to become. By the time she left Columbus for New York, she had married the other main character in Dearborn’s biography: a charming, handsome, fellow Southerner named Reeves McCullers, who wanted to write, too, though he left no evidence of having done so. Reeves was the “prettiest thing” McCullers had ever laid eyes on, and McCullers was the love of his life.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).