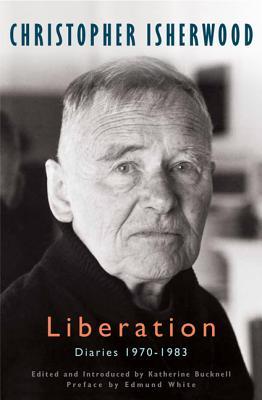

Liberation: Diaries, 1970-1983

Liberation: Diaries, 1970-1983

by Christopher Isherwood

Edited by Katherine Bucknell

HarperCollins. 875 pages, $39.99

TWO YEARS AGO [March-April 2011], I reviewed Christopher Isherwood’s Diaries: The Sixties in this publication, in an essay called “Too Much Information!” The title was mine; the exclamation point was not. While I found much of value in the book, as I had in the previous volume, which covers 1939 to 1960, I registered an objection to the decision by Isherwood’s partner, Don Bachardy, and editor Katherine Bucknell to publish the diaries in full. I wrote, “some editing would have been a kindness to Isherwood, who is spared nothing in these pages.” Now that we have the rest of the diaries, I find myself compelled to reevaluate that criticism.

There is plenty more of the same here: more health and money worries; more self-flagellation for drunkenness and laziness; and more of life with Don, though much of that has improved from the previous decade. In the 70s, at last, the two men found an equilibrium that seemed to be lacking in their earlier years. Liberation provides a narrative of love and contentment that is rather heart-warming: it feels well earned. The final entry for 1971 nicely captures their relationship: “No words can describe how happy I am with Don, just now. But oh how difficult it is to enjoy happiness in and for itself!”

What are readers to expect from a writer’s diary? The entry on the tenuousness of happiness strikes me as a fine example of the kind of “thinking out loud” which makes diaries interesting. That Isherwood acknowledges his love for Don and his life with him, while simultaneously lamenting our tendency to undermine ourselves, is somehow reassuring. We, as readers, recognize something common, something human here, something we all share. But in the million words that constitute Isherwood’s diary, one can find whatever one is looking for. Many critics, including Edmund White in his preface to this volume, have found an off-putting anti-Semitism; some have found a certain kind of older gay male misogyny. Some have found his life-long spiritual journey inspiring, while others have found it laughable or pathetic. Even Isherwood found reading his diaries challenging, as he notes in the summer of 1972: “Have been dipping into my old journals of the early sixties; a mistake. Now I feel sad as shit, but must admit things are much better nowadays. … Is it really good to keep a journal? I loathe doing it at the time and I get depressed when I read it. But it’s such a marvelous treasure trove.”

So, I predict that Isherwood’s diaries will provide you with essentially the Isherwood you knew going in. I do think that the sheer bulk of the diaries may end up, fifty years hence, making them the most significant part of Isherwood’s œuvre. Almost all his work is present here, as is so much of his life. The everyday-ness of it all provides insight into—or at least a vision of—a particular, unique 20th-century life. The diaries elucidate the Isherwood who is best known for his documentary fiction, whether he’s writing about Berlin in the 1930s or Los Angeles in the 1960s. His documentary style evolved into memoir in the 1970s, when he rewrote Berlin from “real life,” peeling away the fictional obfuscations of the earlier versions of the story. This is where Bucknell’s notion of “Liberation” comes in: gay liberation, personal liberation, and spiritual liberation converge in these years of the man’s life and work. Watching an elusive peace become more pervasive in Isherwood’s consciousness, as well as in his personal and public life, is the best reward of this volume, to be sure.

One of the attributes—charms?—of the diary form is the aside, the succinct moment of insight that often reads as a “note to self.” For example, on a visit to London in January of 1973, Isherwood and Bachardy attended a performance of John Osborne’s play A Sense of Detachment, which they did not especially like. After a long paragraph criticizing the play, Isherwood notes parenthetically, “(I don’t mean what I have written to be against John personally. I’m actually trying to describe his failure as a warning to myself. Because all of us writers (nearly) are capable of lapsing into this tone of oracular complacency and making silly pricks out of ourselves.)” For someone who constantly reread his life in his diaries, these notes must have been helpful and reassuring.

often reads as a “note to self.” For example, on a visit to London in January of 1973, Isherwood and Bachardy attended a performance of John Osborne’s play A Sense of Detachment, which they did not especially like. After a long paragraph criticizing the play, Isherwood notes parenthetically, “(I don’t mean what I have written to be against John personally. I’m actually trying to describe his failure as a warning to myself. Because all of us writers (nearly) are capable of lapsing into this tone of oracular complacency and making silly pricks out of ourselves.)” For someone who constantly reread his life in his diaries, these notes must have been helpful and reassuring.

The highlight of 1973 for Isherwood was Oscar night: “Triumph of Cabaret over The Godfather. They only got three awards, we got eight.” The “we” is noteworthy, given that Isherwood never really appreciated the film that made him as rich and famous as he had ever been. That particular Academy Awards night is remembered for another historic reason, which Isherwood also commented on: “Excitement over Brando’s refusal to accept the award, a silly show-biz stunt which was probably nevertheless of some value because it made people remember the Indians. We minorities are like a lot of tiresome (to the majority) children, jumping about yelling, ‘Look at me!’” These comments recall the classroom scene in Isherwood’s masterpiece A Single Man, in which George sounds off about the relationship between majorities and minorities, while demonstrating the Isherwood we often find in the diaries, criticizing (“silly show-biz stunts”), praising (“probably nevertheless of some value”), and identifying with (“we minorities”) all at once.

In September of that year, Isherwood began work on Christopher and His Kind, which could well be considered the source of his liberation. It was his bestseller and marked his most courageous and, in some ways, outrageous coming out story. It was the “truth” of his Berlin years, which confirmed that “to Christopher, Berlin meant boys.” Though he had come out in print in Kathleen and Frank (1972), a biography of his parents that turned out to be, as he realized, “chiefly about Christopher,” it was the retelling of the 1930s that situated Isherwood as a hero of his tribe in the heyday of gay liberation. As he contemplated how to approach writing the book and revisiting this period of his life, he noted:

I’m basing the opening on my diary, but already I’m expanding the material and, I dare to hope, beginning to see how I can work away from mere narrative. My inspiration is Jung’s resolve to “tell my personal myth.” … I don’t want to gossip and bitch. I don’t want to complain and denounce. … I aim for a tone which is positive, good-humored, tough, appreciative—but not goody-goody or mealymouthed. I want to refrain altogether from blaming myself or indulging in guilt. … I want to write about my sex life very frankly and without the least hint of self-defence.

This kind of entry is where the literary interest of the diaries can be found. We see the writer at work, sorting out how to approach his subject matter, how he might do something new and compelling, for himself and for his readers. Certainly, with Christopher and His Kind, Isherwood did just that. He knew that it was working, even as he was struggling with it: “gradually nearing the end of the Berlin section of my book. God, it is hard to put together and I have all manner of doubts and fears, but at the same time I know it is worth doing—oh, far more than that: this book creates a situation in which I can say things I have never—could never have—said in any of my other books.”

Isherwood’s last book, My Guru and His Disciple (1980), is a spiritual memoir describing his devotion to Vedantic Hinduism; it is also an homage to Swami Prabhavananda, his guru for almost forty years. Now in his late seventies, Isherwood was filled with self-doubt and relied heavily on his diaries for material. Unsure about the content he was working with, he worried: “It is still entirely possible that the question, ‘Why are you telling me all this?’ won’t be adequately answered. But, in all my long experience, I have never been able to find anything better than this fumbling my way of getting down to the nerve. I am making an entry today merely to try to start a sequence of diary keeping. These isolated entries are almost worthless. And, I must say, the more I read the later diaries, the more I see how worthwhile diary keeping is.” Worthwhile and meditative—so much of Isherwood’s devotion to Vedanta was about meditation, the discipline and the frustration of it. Diary keeping was like that for him—a discipline, a rigorous effort, and a way of justifying to himself that he was working, attending to his vocation.

Also in his seventies, as the diaries show, Isherwood finally embraced the role of “great gay uncle.” While he was never an activist, he records his involvement with gay issues and causes—watching a televised debate between the Reverend Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church, and Representative John Briggs about California’s Proposition 6 in 1978; speaking at gay events and bookstores; participating in gay pride parades and marches over the years; appearing in gay magazines and newspapers, such as The Advocate and After Dark. In September of 1977, Isherwood and Bachardy went to the Hollywood Bowl for the “Star-Spangled Night for Human Rights.” While he feared that the event was “a flop,” he relished the “mere getting together of all those thousands of gays … a triumph and a mutual assurance that we all really exist, along with our demands and our wrongs and our hopes. … [It] was extraordinarily moving. You felt the eagerness of all those thousands to be accepted, to belong, to have a place of their very own in this land, which isn’t free enough to accept them.”

Liberation contains something for everyone, the lovers and the haters, the writers and the readers. But what about the question of “too much information”? It is almost as if Isherwood anticipated this objection in his first entry for 1978, when he was feeling ambivalent about keeping the diary and turned to Virginia Woolf for inspiration—her diaries were published in five volumes throughout the 1970s and 80s: “Somehow, the abridged diary that was published in 1953 left me with a quite different and much less stimulating impression [of Woolf]. She seemed to be so preoccupied with people’s opinions of her books. This volume makes her seem much more positive, much less self-preoccupied.” I’m not sure that the unabridged Isherwood gives that same positive spin, but then, if an editor starts cutting, how much and what can be cut before we get someone else’s version of the diaries, one that is reader-friendly and portable but not quite indicative of the man in his daily life? With less anxiety about his weight, less drinking, less annoyance with the weather or various aches and pains, what of the man is lost? And isn’t that, the stuff of life, what we really want and hope to glimpse in his diaries?

Chris Freeman, associate professor of English at the university of southern California’s Dornsife College, is co-editing a collection on Isherwood, with James Berg, to be published in 2014.