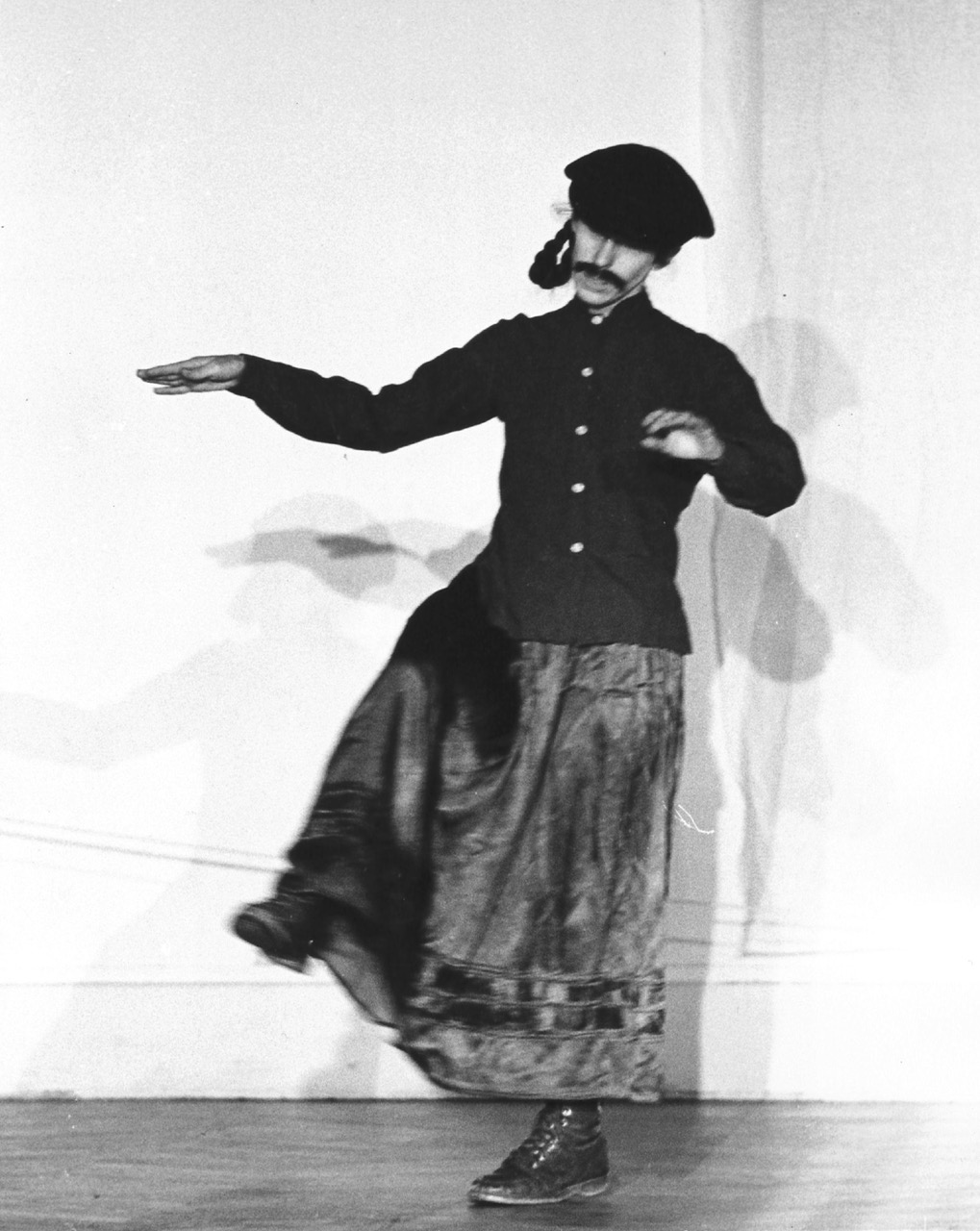

FOR OVER FIFTY YEARS, Meredith Monk has created critically acclaimed musical, operatic, theatrical, cinematic, and visual installation works. Her performance work incorporates three-octave vocalizing, idiosyncratic gestural movement, film, and luminous stage design, inviting audiences to experience archetypal, dreamlike spectacles. The New Yorker called her “as close to a complete performing artist as American culture offers.”

Monk came of age artistically in 1960s New York. Audiences were ushered in and out of her live-work loft as part of multi-venue epics that included site-specific components in the Guggenheim Museum and a parking lot in lower Manhattan. Largescale events with 150-member casts alternated with intimate pieces for solo voice and wine glass. These days, her work continues to be performed in a variety of settings—in concert halls, galleries, and site-specific venues around the world.

Photo by Beatrice Heyligers

Monk has received fellowships from major foundations and was the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. She was composer in residence at Carnegie Hall in the 2014-15 season, and received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama in 2015.

Monk’s polyphonic music has been recorded by her own ensemble in eighteen recordings. Jean-Luc Goddard, the Coen brothers, Terrence Malick, and David Byrne have featured her music in films. The Kronos Quartet, St. Louis Symphony, and San Francisco Symphony have commissioned new scores. In April, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas included her work in a Pride concert with the San Francisco Symphony.

I spoke with Meredith Monk in March while she was in Minneapolis visiting the Walker Art Center, which acquired material from one of her first iconic performances, 16 Millimeter Earrings (1966/98).

John Killacky: When you graduated from Sarah Lawrence College and moved to New York in the mid-1960s, did you ever dream that you would have the extraordinary career you’ve had?

Meredith Monk: I wasn’t even thinking in those terms. When I first came to New York, I did a piece called “Break” that was included in “New Voices in the Arts” on WNET, Channel 13, in New York. The announcer asked, “What do you really want to have happen in your life?” I said, “I just want to do good work.” That was my goal.

JK: In talking about your film Book of Days (1988), you said: “In all my work, I attempt to create a world in which the audience has a chance to see things that they take for granted, or never think about, in a new way.” Talk more about your creative process.

MM: Each piece is a world unto itself, having its own laws and principles. Part of the process is trying to honor and figure out what those principles are. It’s listening for what the piece wants. When I am making a piece, even after all these years, fear comes up each time. Hanging out in the unknown is not comfortable, but by working and trying to be playful about it, and coming in with a beginner’s mind and no expectations, then just taking it little by little, step by step, I might get a moment or a clue or something that I’ve never heard or done or seen before. When that happens, the fear goes away and curiosity starts taking over, and I know I am on the right path.

JK: For over five decades, your work has been deemed avant-garde. What does this mean to you?

MM: I’ve always had a hard time with that term. It has a certain historical taint to me. In my work, I try to find fresh solutions or perceptions. At the same time, I feel my work circles back to something very ancient. Because of people’s associations with the word avant-garde, they think it is going to be crazy or inaccessible—off-putting rather than inclusive. That makes me sad because in some ways my work is very accessible.

JK: When you were fifty you wrote, “I think the hardest aspect of having done something for a long time is the sense of carrying around a lot of baggage that has to be discarded to be able to begin again.” Now that you are approaching 75, is that burden even heavier?

MM: In some ways, no. I keep on shedding [baggage]to get to something more essential, and that opens up a lot of space to find something new. I’m working on a new piece called Cellular Songs. It’s going to be for five women in my ensemble. We’ve been working on trio a cappella pieces. They’re very intricate harmonically and rhythmically—very new for me. I feel fortunate that new things are coming up for me.

JK: You recently revived your Holocaust-inspired masterpiece Quarry from 1976. What was it like to revisit this work?

MM: We did the darkest section of the piece at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. The “March” section has to do with dictatorship and fascism. There’s a rally inspired by Hitler youth rallies: very athletic movement and guttural rhythmic sounds—shockingly powerful. At the very end of that rally, people melt into tableaus—sitting, waiting to be taken away. Because of what is going on in the world, I think it’s so important that this historical context be taught to young people.

JK: Oftentimes, even in the arts, women are the innovators, but men get more recognition. Has this been your experience?

MM: I would say, yes. I find it hard to talk about, because I could start ranting.

JK: One of your most poignant works, the Grammy-nominated impermanence (2006), was created after the death of Mieke van Hoek, your long-term partner. Have you experienced homophobia?

MM: I am very aware of the pain of it, but I’ve been fortunate that the artistic world that I’ve been a part of all these years has been very accepting. I was 22 years with Mieke. My family and friends were extremely open. They loved and welcomed her. I feel so grateful for that.

JK: Before Mieke, you were with both men and women. Has it been complicated to identify as bisexual?

MM: There was a time when people in the gay community were suspicious of someone identifying as bi, because there seemed to be a repressive or fearful aspect to it. That was very hard for me, because I’ve had meaningful relationships with both men and women. The fluidity of bi identity is important for me. As an artist, I want insight into both sides of life.

John R. Killacky is executive director of the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts in Burlington, VT.