Queer Beats: How the Beats Turned America On to Sex

Queer Beats: How the Beats Turned America On to Sex

Edited by Regina Marler

Cleis Press

209 pages, $16.95 (paper)

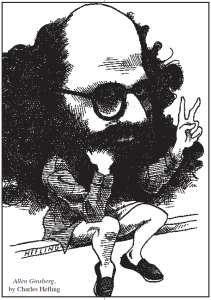

THE GROUP of postwar American writers known as the Beat Generation, of whom the best known are Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs, produced a body of work that continues to attract new generations of readers. Nearly all of the principal Beat writings remain in print, and biographies and studies of Beat writers and their work have become something of a cottage industry. Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs are now cult heroes. This has come about as a result of their writings, but also—and perhaps even more so—because of the image they projected and the carefree, iconoclastic lifestyle they exemplified.

From the accounts of Kerouac’s speed-fueled writing marathons to the descriptions of Burroughs and Ginsberg’s quest for the legendary hallucinogen yage, much has been written about the muse-like role that drugs played in the lives and writings of the Beats. In contrast, though it is well known that Ginsberg and Burroughs were homosexual and that Kerouac was bisexual, not much has been written about their sexuality, at least until recently, and few attempts have been made to explore the complicated, sometimes conflicted, sex lives of these writers. But in the last few years, scholars and biographers have started to open up this territory. Ellis Amburn’s 1998 book Subterranean Kerouac, for example, delved deeply into the writer’s ambiguous sexuality. Regina Marler’s new anthology, Queer Beats, breaks new ground in chronicling Beat sexuality.

In postwar, pre-Stonewall America, few people were eager to proclaim their homosexuality, and even the rebellious Beats were initially timid about the subject. Ginsberg, who later celebrated the homoerotic in his poetry and became a kind of latter-day Whitman, was initially conflicted about his sexual identity. Kerouac, who slept with men many times, nonetheless made sure to project a decidedly macho image. And Burroughs never quite embraced his homosexuality. But all three writers dealt with gay themes in their writings, albeit to varying degrees. Nakedness was their muse, and they used it to challenge the conventions of “civilized” America. Marler’s book assembles writings by and about Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Kerouac, as well as several others, to present a uniquely effective portrait of how the Beats lived, and how they portrayed their sexuality.

Marler draws upon the Beats’ fiction, poetry and autobiography, and also delves into their correspondence and journals, plus some unpublished works. She finds a place for lesser-known Beats, such as Herbert  Huncke, perhaps the most openly gay writer of the entire group, and Alan Ansen, “the best ‘undiscovered’ Beat poet.” She includes the work of non-Beat writers such as Gore Vidal and straight writers like Norman Mailer, writers who admired the Beats and intersected with their circle at a number of points in their lives. After a lengthy introduction in which she places in context their “revolution of the flesh as well as the word,” Marler presents selections from their works, organized into three groups according to subject matter, each with a separate introduction. And it’s all there before us: the Beats’ lifestyle of excess; their relationships with the men who inspired their writing; their emergence and growing influence on American culture.

Huncke, perhaps the most openly gay writer of the entire group, and Alan Ansen, “the best ‘undiscovered’ Beat poet.” She includes the work of non-Beat writers such as Gore Vidal and straight writers like Norman Mailer, writers who admired the Beats and intersected with their circle at a number of points in their lives. After a lengthy introduction in which she places in context their “revolution of the flesh as well as the word,” Marler presents selections from their works, organized into three groups according to subject matter, each with a separate introduction. And it’s all there before us: the Beats’ lifestyle of excess; their relationships with the men who inspired their writing; their emergence and growing influence on American culture.

The major Beat documents are well represented: Ginberg’s Howl, Kerouac’s On the Road, and Burroughs’ Queer. Also included are many letters and excerpts from journals and memoirs, which give the anthology an almost conversational quality and help carry the narrative of the Beats’ collective drama. For example, in chronicling the famous dalliance between Kerouac and Vidal, Marler offers up Vidal’s engaging description of the affair from his memoir Palimpsest (and presents it as a kind of antidote to Kerouac’s fictional portrayal of it in his novel The Subterraneans). A brief excerpt from Harold Norse’s Memoirs of a Bastard Angel provides a glimpse into a somewhat wild Beat party.

There are some delightful curiosities in Queer Beats. One is Huncke’s essay, “On Meeting Kinsey,” in which he describes his impressions on meeting and becoming a subject for the famous sex researcher. Another is Norman Mailer’s defense of Burroughs’s masculinity. Marler also includes a woman’s perspective on the Beats with Diane Di Prima’s Memoirs of a Beatnik. A short story by Jane Bowles, the wife of Beat-by-association writer Paul Bowles, is also included. An engaging mix of fiction, poetry, and memoir, Marler’s collection is well-rounded and fascinating. Though it focuses on the Beats’ sexuality, it also provides a broader introduction to the work of this seminal group of writers.