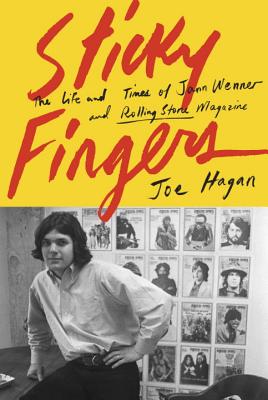

Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine

Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine

by Joe Hagan

Knopf. 547 pages, $29.95

JANN WENNER is one of those people who seems to have emerged from the womb knowing exactly what he wanted to do. He had journalism in his blood early on. He not only created a neighborhood newspaper as a child but also sold subscriptions to it. As the founder, editor, and driving force behind Rolling Stone magazine, Wenner made a unique imprint on American culture and managed—through moxie, good timing, and sheer luck—to create what has become a media legend. He could not have done it without grand ambition, cockiness, and a nearly ruthless drive to succeed. And he could not have done it alone. His ability to court the right people at the right time was a key element in Rolling Stone’s early success. But Wenner also made a lot of enemies along the way. Joe Hagan chronicles nearly every minute of the story in his undeniably fascinating biography.

A brief scan of the dust-jacket blurbs gives a taste of the famous names (and infamous stories) contained within the book’s 500-plus pages. The cast of characters includes Hunter S. Thompson, Bruce Springsteen, Annie Leibovitz, Elton John, Mick Jagger, Truman Capote, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Bette Midler, Bob Dylan, Bono, and David Geffen, among many others. Rolling Stonedidn’t just cover the music scene and youth culture; it helped to shape and define them.

Many of the magazine’s early writers—the roster included Ben Fong-Torres, Joe Eszterhas, P. J. O’Rourke, and Matt Taibbi—became stories in themselves. Hunter Thompson and Tom Wolfe were the standardbearers of the “New Journalism,” a long-form genre that employed novelistic techniques. A significant portion of their work first appeared in the pages of Rolling Stone. In this way, Wenner was instrumental in changing the face of cultural and political reporting.

The book’s title is a reference to the notorious 1971 Rolling Stones album cover by Andy Warhol, which featured a black-and-white crotch shot of a pair of jeans, complete with a working zipper. (The thighs and package filling out those jeans were said to belong to Joe Dallesandro, the sexy actor of Warhol’s films.) Even for the early 1970s, the cover’s blatant reference to male masturbation was audacious. It was also the start of treating male rock stars as sex symbols, a practice that Jann Wenner, a closeted gay man, made sure to capitalize on in his magazine.  In 1972, Rolling Stonefeatured a tantalizingly racy photograph of teen idol David Cassidy on its cover (the Annie Leibovitz photograph made it clear that Cassidy wasn’t just shirtless) and a suggestive centerfold inside. Though Leibovitz soon regretted the photo, the issue sold thousands of copies, setting a record at the time, and Wenner was delighted with it. He correctly intuited that there were many young men who lusted after male rockers as much as the girls did, and he was happy to give them all something to dream on.

In 1972, Rolling Stonefeatured a tantalizingly racy photograph of teen idol David Cassidy on its cover (the Annie Leibovitz photograph made it clear that Cassidy wasn’t just shirtless) and a suggestive centerfold inside. Though Leibovitz soon regretted the photo, the issue sold thousands of copies, setting a record at the time, and Wenner was delighted with it. He correctly intuited that there were many young men who lusted after male rockers as much as the girls did, and he was happy to give them all something to dream on.

Many people at the time assumed (and perhaps many still do) that the magazine was named after Mick Jagger’s band, but Wenner insists that the idea came from an essay on youth culture, “Like a Rolling Stone,” written by his friend and mentor Ralph Gleason, who borrowed the phrase from the Bob Dylan song and suggested it for the magazine. Wenner agreed, but Jagger, a shrewd businessman, wasn’t convinced, and he and Wenner danced back and forth for decades before eventually laying to rest a legal dispute over rights to the name.

Hagan’s biography is a monumental effort. Wenner was nearly obsessive about maintaining his image, and he amassed an archive of journals, press clippings, photographs, and other materials to back it up (at one point, he even built a nuclear-blast-proof vault to house the trove). Hagan had access to all of it. He also conducted interviews with hundreds of celebrities, Rolling Stonestaffers, and others who knew and worked with Wenner.

The picture of the media titan that emerges is not always flattering. Wenner was widely regarded as brash, egomaniacal, and self-serving. He could be downright nasty. In an afterword, Hagan notes that many suggested he steer clear of Wenner and not do the book. It is to his credit that Wenner agreed to be interviewed for this warts-and-all biography.

One of the most fascinating elements of the story is the long, troubled marriage and business partnership of Jann and Jane Wenner. Most of the trouble resulted from Jann’s closeted sexuality and many gay liaisons. This appears to have been an open secret, though many close friends claim to have been surprised when Wenner finally came out in 1995 after he left Jane for Matt Nye, a handsome young fashion designer. Hagan’s book is replete with juicy tales of Wenner’s exploits, including his arrest, at age twelve, for some apparently gay “horseplay” at a library with the son of the local sheriff. In the decades that followed, rumors proliferated about romances, or at least hookups, with Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, Richard Gere, et al. Of course, Wenner was also said to have bedded many women, among them Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Hagan writes Wenner’s story with the flair of a novelist. As if channeling the techniques of the New Journalists, Hagan often opens his chapters with deftly drawn scenes that capture a particularly dramatic moment. He can be equally effective with cliffhangers at chapters’ ends (“He flicked on the television. John Lennon was dead.”). Rolling Stone was a part of many watershed cultural moments, and the cast of characters in the magazine’s history, from the bit players to the megastars, would be a daunting task for any biographer to manage, but Hagan pulls it off. Sticky Fingers is a valuable chronicle and a superbly entertaining book.

Jim Nawrocki, a frequent reviewer in these pages, is a writer based in San Francisco.