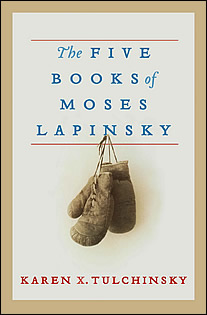

The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky

The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky

by Karen X. Tulchinsky

Raincoast Books. 496 pages, $15.95

CANADIAN WRITER Karen Tulchinsky is perhaps best known to American readers for her erotic short fiction, but this sprawling family drama will change her reputation entirely. The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky is a fully engaging, compulsively readable stroll—sometimes a race—through the mean streets of Depression-era Toronto with the Lapinsky brothers. It’s told by Moses Nino Lapinsky, a late-middle-aged history professor and an openly gay man. His uncle, also gay, was the highly decorated Canadian war hero Lenny Lapinsky. Moses sets each of the five main sections of the novel in historic context, then lets his family members speak for themselves.

It’s apparent that Tulchinsky listened very closely to the stories her elders told her about life in “the dirty thirties,” as that era was sometimes called in Canada. I should know: all her characters lived on the exact same streets, went to the same stores, and attended the same high school as my mother and her family. There are four Canadian-born sons of Yacov and Sophie Lapinsky: Sid, the stable, sensible one; Sonny, who becomes a world boxing champion (and is the father of Moses Nino Lapinsky); Lenny, who can be “read” as gay almost immediately; and Izzy, the youngest.

The whole family feels intense guilt and responsibility for Izzy, who was severely beaten and left permanently brain damaged by rioters at Christie Pitts, a recreational park, in 1933. This horrifically violent event, well-documented in Canadian history, set Canadian Nazi youths against Jewish youths. Toronto police were ineffectual at breaking up the fights. One of the youths who was involved in Izzy’s beating ends up in the Canadian Army and, in the sort of coincidence that novels are built upon, becomes a friend of Lenny, who did well in the Army. No sexual contact actually takes place between the two men—except, that is, in Lenny’s mind. Lenny had been a bookworm, a dreamer, a frequent patron of the public library, mentored by a rather dashing 25-year-old man who worked there and took serious interest in Lenny’s choice of literature. Lenny became a proofreader at a local Yiddish newspaper, but when his mentor suddenly moved away, Lenny, “lost and alone,” enlisted in the Army. Tulchinsky’s vivid descriptions of his wartime experiences, at once touching and terrifying, ring true, and it’s apparent that she relished working on a topic so very different from what she’s previously written.

The many plots and subplots of this longish novel—Sonny’s life as a gangster, his marriage to a shiksa (non-Jew), his father Yacov’s unwillingness to accept the mixed marriage and Sophie’s secret efforts to see her grandchildren; Sid and his saintly wife Ruthie’s struggle with infertility; Sophie’s undying love for her sons and her incessant worries about where the next nickel for a loaf of bread will come from; Yacov’s efforts (with his cousin Max) to keep the family business, a discount shop, afloat—are thoroughly dissected, sometimes more than once and from differing viewpoints. There is a final chapter in which the plot lines are tied together, although an argument could be made for integrating the disparate stories a bit earlier in the book.

For all its length, the novel never becomes tedious, in large part because Tulchinsky develops each character as a fully realized person. While there is the occasional stilted passage, and a few scenes of shtetl life in Yacov’s childhood home in the Pale of the Settlement sound a little too much like Fiddler on the Roof, this is a very ambitious novel that succeeds in recounting a family saga through a fascinating and important period in Candadian history.