WHAT BRINGS AUDIENCES to the theater is “the expectation that the miracle of communication will take place,” explains a protester to the board of a city arts complex in “Hidden Agendas,” a one-act play that Terrence McNally wrote in 1994 in response to government-inspired attempts to censor an exhibition of the late Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs. “Words, sounds, gestures, feelings, thoughts! The things that connect us and make us human. The hope for that connection!” The purpose of theater, McNally says in a subsequent interview, is to “find out” and explore “what connects us” as human beings. For McNally, theater’s most important function is to create community by bridging gaps opened between people by differences in race, religion, gender, and most particularly sexual orientation.

Perhaps the greatest irony of McNally’s highly productive career is that the play that was supposed to bring people together in an appreciation of our common humanity, Corpus Christi, would prove his most divisive. This play draws upon the biblical narrative of Jesus’ nativity, ministry, and passion to tell the story of a gay teenager’s coming out and subsequent death in a bigoted town in post-war Texas. Corpus Christi juxtaposes the transformative power of a religion

original production by New York’s Lincoln Center Theater

that is charitable, all-embracing, and respectful of difference with the destructive power of religionists who divide the world into the “godly” and the “sinful” and reserve for themselves the authority to define and persecute the latter in the name of righteousness. When the play opened on October 13, 1998, at the Manhattan Theatre Club (MTC) in New York City, it was denounced from local pulpits, picketed by religious demonstrators, and—in the face of anonymous telephone threats to burn down the theater, kill the staff, and “exterminate” the playwright—forced to require ticket holders to pass through metal detectors before taking their seats. When the play premiered in London a year later, a Muslim group called Defenders of the Messenger Jesus issued a fatwa (death sentence) against McNally for blaspheming a figure that they revere as a prophet.

Subsequent regional productions have proven no less magnetic as sites of contention. In summer 2001, for example, when an undergraduate theatre major decided to direct a black box production of the play as his senior thesis on a state university campus in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, a group that included eleven Indiana taxpayers, 22 members of the state General Assembly, and ten members of the Purdue University Board of Trustees filed a motion asking the U.S. District Court to stop production of the play on the grounds that it constituted an “undisguised attack on Christianity” at a state-funded campus, thus violating the First Amendment. Thirty-six Fort Wayne churches took out newspaper ads to announce the dates and times of services at which Christians and other interested individuals might learn who the “real” Jesus was. One Catholic “anti-defamation” group threatened to have its members fill every parking space on campus the day of the show’s initial performance and thus cause ticket holders themselves to disrupt the production by arriving unavoidably late.

It is difficult to understand how any person genuinely committed to Jesus’ message of universal love could quarrel with McNally’s play, whose message is as deeply humane as it is grounded in biblical teachings. Even while wrestling with his own sexual difference, the play’s protagonist, whose name is Joshua (Jesus in Hebrew), dedicates himself to showing humans who “are not happy”—gays and straights alike who “sicken and die and turn away from love”—that there is another way to live, a “way of love and generosity and self-peace.” Echoing the Christian mystery of the dual nature of Jesus, which held him to be both fully human and fully divine, Joshua teaches that every person is simultaneously “ordinary” and “divine.” The world is not at peace, he reveals, because rather than revering the portion of divinity that can be found in every individual, some people are driven to denigrate others in order to feel better about themselves. Joshua advocates a religion in which the only way to hear the voice of God is to listen to another person’s heart beating, thus making sympathy and compassion, as well as a capacity for intimacy, the cardinal virtues of any genuinely religious person. Like the biblical Jesus, McNally’s Joshua insists that “all who do not love all men are against Me,” the practice of any kind of discrimination proving a violation of the Christian imperative to love even your enemies.

“Us” vs. “Them”

Corpus Christi’s troubles began when the play was announced for MTC’s fall 1998 season. Summarizing only second-hand accounts of the play months in advance of its opening, the New York Post (a Rupert Murdoch tabloid) incited public ire when it inaccurately reported that the play, initially to be produced with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, would depict onstage a gay Jesus performing anal and/or oral sex on his apostles. Subsequent comments by William A. Donohue, president of the politically aggressive Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, leave unclear whether he surreptitiously obtained a copy of the original script or merely guessed what McNally’s approach to the Jesus legend might be, perhaps based on the widely noted presence of male frontal nudity and a simulated sex act in Love! Valour! Compassion!

In any event, Donohue threatened to “wage a war that no one will forget” against any theater that dared to support what he irrationally labeled McNally’s “campaign to attack Catholics,” and organized nightly demonstrations outside the theater that did produce the play. Donohue pointed to a number of McNally’s transformations from a biblical to a modern setting: the wedding feast at Cana becomes a same-sex commitment ceremony performed by Joshua for two of his followers; Jesus’ association with social outcasts like a tax collector and a prostitute turns into Joshua’s friendship with a male hustler; and his healing of lepers becomes Joshua’s compassion for AIDS sufferers. In a diatribe against the play, Donohue accused McNally of “homosexual hate speech” aimed at Catholic nuns and priests. His ire seemed particularly provoked by two brief scenes, one in which a parish priest humiliates Joshua at football practice and another when a sympathetic nun coaches Joshua to sing “I’m in Love with a Wonderful Guy” at a rehearsal.

In the preface to the published text of his play, McNally echoes fellow gay writer W. H. Auden’s insistence that “we must love one another or die,” and draws a parallel between events in biblical Judea nearly two thousand years ago and the horrific beating of Matthew Shepard, the gay college student who was tied to a fence in rural Wyoming, viciously beaten, and left there to die—an event that occurred the very week that Corpus Christi opened in New York. At the conclusion of the play, as the disciples gather around Joshua’s crucified body, they ponder sadly why Joshua should have aroused such homicidal hatred in his attackers when, ironically, “He loved every one of us. That’s all He was about.” Perhaps nothing makes clearer McNally’s actual intention than the actors offering the blessing “Peace be with you” to the departing audience, much as the celebrant encourages his congregation to go in peace at the close of the Roman Catholic mass.

While the general thrust of McNally’s play is deeply pacific, the language of his critics continues to be highly divisive, often invoking an “us versus them” type of formulation. Some homosexuals may believe in God, Donohue conceded, but “they don’t want to believe in God as we know Him” (emphasis added). The unexplained “we” could refer either to specific members of the Catholic League or possibly to anyone sharing their homophobic bias. When asked by National Public Radio reporter Robert Siegel to explain what specifically upset him about the play, Indiana state senator Michael Young sputtered, in a confusing welter of pronouns that betrays intense passion but little rationality, “First of all, that they portray our Savior Jesus Christ as a homosexual, that he has homosexual affairs with his disciples, that he denies that God is the Father, the language that is used, the acts that are used. I mean, they’re perverse, vile, disgusting. And that is our problem with this” (emphasis added).

“My Christ was not a fornicator, an adulterer or a homosexual,” one of the plaintiffs in the Indiana lawsuit protested. The speaker, however, never made clear why he assumed that McNally thought Christ to be either a fornicator or an adulterer, as the play presents Joshua as unmarried, so he could not by definition commit adultery, and it does not suggest that he has an active sex life. Ironically, while repeatedly insisting on their own right to fashion a god according to their own needs (“my Christ,” “our Savior,” “God as we know Him”), and to “wage a war that no one will forget” against anyone who doesn’t accept their version of the truth, McNally’s detractors were particularly incensed by the actors’ concession at the close of the play that “Maybe other people have told His story better. … This was our way.” Such a statement is a humble acknowledgment of the particular truth to which the speakers are able to bear witness, not an angry assertion of authoritative knowledge of God’s nature and intentions. It readily accepts that others may have experienced Joshua differently, much as the four Gospels themselves witness to radically different understandings of Jesus’ nature and ministry. Perhaps the most painful aspect of the controversy surrounding Corpus Christi is that people who see the world as “us versus them” should reject the play because it so generously accepts the divinity of all persons.

Mundane and Sublime

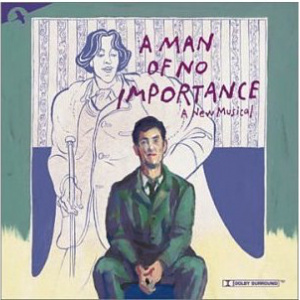

Writing in the October 1998 issue of American Spectator at the time of Corpus Christi’s premiere, commentator Roger Kimball acknowledged that he was curious to see “how McNally responds to the controversy that his work has sparked.” In the face of such virulent, religiously organized homophobia, a less temperate playwright—Larry Kramer, for instance—might have gone on the offensive, angrily denouncing his accusers and organizing his own counter-protests. McNally chose instead to write a musical stage adaptation of the 1994 film A Man of No Importance, in which a closeted, middle-aged city bus conductor in 1960’s Dublin with a passion for Oscar Wilde has to defend his amateur production of Wilde’s Salomé from charges of blasphemy leveled by a self-righteous parishioner. Written in the aftermath of the furor over Corpus Christi, A Man of No Importance may be viewed as McNally’s meditation on the power of theatre to create community and to transform how people think.

The movie’s protagonist, Alfie Byrne, incarnates the mystery enunciated in Corpus Christi that all people, however ordinary, “are divine.” On the one hand, Alfie is as pedestrian a figure as one might conceive: a lower middle class, 41-year-old bus conductor living with an older sister who has forestalled marriage in order to keep house for him. On the other hand, Alfie is different from his family and fellow parishioners in that he’s an indefatigable reader, cooks such exotic foods as spaghetti Bolognese, secretly longs for a younger male coworker that he’s nicknamed “Bosie” (after Wilde’s pet name for his lover, Alfred Lord Douglas), and puts all of his energy into organizing the parish’s annual play.

Father Kenny, the parish priest, recognizes from the outset that the theatre “is a holy place to Alfie Byrne,” and that Alfie loves the stage with the same passionate intensity that “some men love women.” Theatre for Alfie and his associates is a sacrament, a way of investing ordinary life with something extraordinary or divine—much the same way, Alfie tells Robbie, that Oscar Wilde made something so innocuous as a cucumber sandwich “immortal” on the night that The Importance of Being Earnest premiered (“a night the mundane became sublime”). No one denies that the St. Imelda Players are poor performers, yet when Father Kenny cautions Alfie that their last production was “bloody awful,” Alfie replies sympathetically: “You may be right but we had a grand time thinking we were bloody wonderful.” As in so many of McNally’s plays that deal with the nature of performance (It’s Only a Play, for example, or, most recently, Dedication), theatre is valued not so much in terms of the final, polished production that is presented to an audience, but as the occasion to create community among those involved.

Art, Alfie recognizes, challenges people to see beauty where they hadn’t seen it before, to consider aspects of their surroundings to which they had been oblivious, and to hear language used in a way that reveals deeper truths and mysteries than that of everyday life. For example, on “a rainy Dublin morning,” when the sky is “a leaden gray,” Alfie looks upon Robbie Faye, the driver of his bus, not as a petty bourgeois coworker whose greatest pleasure comes from knocking back a few pints with the boys at the local pub each evening, but as a “rare Athenian youth” piloting the chariot of Apollo. Alfie’s entertaining the passengers on his route with a daily poetry reading transforms the group into a close community of friends who share something rare. Alfie’s theatricality reveals the sublime in the mundane, and dares his companions to dream of a world outside the pedestrian one.

It is this last aspect of theater that enrages Alfie’s antagonists so. The leaden grey world outside Alfie’s bus and St. Imelda’s theater—the two spaces in the play where imagination (especially a gay imagination) is allowed to thrive—resembles nothing so much as the post-war Texas town dramatized in McNally’s Corpus Christi. As Adele sings of the censorious neighbors who drove her out of her native village to seek a comforting anonymity in Dublin,

They don’t raise dreamers in Roscommon

Only onions and potatoes. …

They have their football and their Bibles

And they don’t believe in art.

And as occurred in the very public debate surrounding the production of McNally’s Corpus Christi, the parish Sodality’s discussion of Alfie’s choice of Salomé becomes an attack upon “dreamers” by those neighbors who are frightened of any challenge to the ill-informed, unimaginative status quo. We are living in “confusing times,” Carney tells Alfie, when people are in danger of losing their way morally and desperately need the firm guidance of the church. The sheer sensuality of Wilde’s Salomé makes the play a provocation to immoral behavior, Carney feels; worse, the play’s appropriation of a biblical story for such a purpose renders it blasphemous. When Alfie protests that Salomé is “a masterpiece of dramatic literature,” Carney angrily replies that “To a heathen atheist your play may be some kind of masterpiece. To a devout Catholic it is an affront to everything our Lord Jesus Christ stretched out his arms and died for.”

Carney’s division of the world into sheep (that is, devout, socially conservative religious believers) and goats (sexually immoral atheists who mock their supposed superiors) echoes the “us versus them” mentality of William Donohue, McNally’s principal antagonist in the fight over Corpus Christi. And Alfie’s pained confusion concerning the community’s response to Salomé surely reflects some of McNally’s own trauma over the controversy surrounding Corpus Christi. Significantly, while McNally does not blunt the brutality of Carney’s moralistic posturing, he is also careful not to lose sight of the dark comedy in which the beleaguered Alfie finds himself trapped. For example, as Carney prepares to read aloud the most offensive portions of Salomé to Lil, he can barely contain his excitement even while warning her that the play “is filth, unadulterated pornographic filth.” His contradictory instructions to Lil—“Just listen to this. Are you ready? Close your ears”—enact the contradiction inherent in most acts of censorship: rather than simply looking away from or refusing to listen to what they find offensive, self-righteous people hypocritically use the occasion of protesting someone else’s transgression to indulge vicariously in transgression themselves.

A Man of No Importance forms part of McNally’s ongoing meditation upon the nature of performance. Because the repression of desire only strengthens those disruptive feelings, a shadow of Wilde counsels Alfie: “The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it.” Critics offended by Joshua’s affair with Judas in Corpus Christi have proven equally unable to understand why Alfie’s appropriating the costume for which Wilde was criticized in his prosecution for public vice should prove ultimately so liberating to him. Alfie’s emulation of Wilde is not an instance of gay masochism, of a need to be punished for desires of which one is ashamed. Rather, it stems from a recognition that fear of desire can turn one into a person like Carney, who destroys others in the name of a dead but comforting principle, and who doubles in the play as the Marquess of Queensbury, the antagonist who brought about Wilde’s disgrace and imprisonment. Alfie’s dressing as Wilde to brave public opinion and “perform” his desire of another male recognizes how theater leads one to discover a truer, more authentic self. The paradox of theater, as McNally has most recently explored in Dedication (2005), is that a world which is itself an illusion should be capable of revealing deeper, more authentic truth.

Alfie learns from his “mentor” Oscar Wilde to accept that life is theatre in the richest sense possible, holding the possibility of fashioning a truer self than society or the “real” world allows. And, in becoming a more authentic person, Alfie suddenly finds himself at the center of a more genuine and meaningful community. As their initial shock at the exposure of Alfie’s homosexuality wears off, Alfie’s sister and friends rally around him, determined to continue rehearsals and find another place to perform Salomé—much the same way as the members of the New York intelligentsia rallied in support of McNally when the MTC initially bowed to protestors’ demands that Corpus Christi be canceled. Fellow playwright Tony Kushner and others threatened to sever all ties with the MTC if it caved to censorship, while television producer Norman Lear organized his People for the American Way in nightly counter-demonstrations outside the theater once the MTC reversed itself and rescheduled the play.

Alfie, thus, not only learns from theater how to refashion himself, but in so doing succeeds in refashioning his community as well. From the tawdry and mundane emerges something sublime; a man of no importance proves indeed divine.

Conclusion: Absolute Humility

“There’s only one thing for me now,” Alfie understands after his beating, “absolute humility.” The essential humility of McNally’s theatre is the primary indicator of its humanity, and remains perhaps the feature which is least understood by his critics, gay and straight alike. A McNally play is characterized by the simplest of sets (a Hell’s Kitchen studio apartment in Frankie and Johnny, a white box for A Perfect Ganesh, the vaguely suggested interior of a Victorian house for Love! Valour! Compassion!) and by the simplest of denouements (Johnny sucking the blood from Frankie’s cut finger, Margaret marveling at the beauty of an elderly woman bathing in the Ganges, Perry assuring Buzz that he and Arthur will be there to hold him in his last hours). But in its “absolute humility,” McNally’s theater offers a series of simple actions that prove capable of connecting people and “mak[ing]us human”: Clarence’s ache for “Shakespeare, Florence [and]someone in the park,” Jerry’s willingness to expose his insecurities by going “the full monty,” Sally’s overcoming her fear that the water in her brother’s Fire Island swimming pool may harbor the AIDS virus that killed him.

Ironically, it was the “absolute humility” of McNally’s Corpus Christi that finally proved most upsetting to its critics. New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley quipped that the most exciting part of the evening was passing through the metal detectors, while William Donohue himself observed that the audience was “disappointed” that the play didn’t offer gratuitous nudity and simulated sex acts—features, needless to say, that were never actually a part of the play except in Donohue’s own overwrought imagination. Apparently, the production’s emphasis upon connection belied audience expectations of confrontation—that is, even members of the theater community attended a performance anticipating the more aggressive kind of theater experience that Donohue’s pre-production hysteria had led them to expect.

The controversy surrounding McNally’s Corpus Christi and the answer that he makes to his critics in A Man of No Importance help frame the question of whether McNally is a gay playwright who writes plays on recognizably gay topics or in the service of a gay agenda—or whether he is a playwright who just happens to be gay and wants to discuss the issues that connect us and make us all, gay or straight, human. He is, much to the disappointment of some gay critics, clearly the latter type of playwright, leading even generally sympathetic audience members sometimes to misinterpret his intentions. In Still Acting Gay: Male Homosexuality in Modern Drama (2000), for example, John Clum objects that “even I, a secular humanist, was bothered by the notion [in Corpus Christi]that Christ was crucified primarily because he was gay and that the most revolutionary thing he did was perform a gay marriage. … Gayness does not make us inferior, but it sure as hell does not make us divine (not literally, anyway).” Rather, McNally asserts that all persons, heterosexual as well as homosexual, are divine, making it a sacrilege to deny any person his or her full humanity.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is completing a book titled “Something about Grace: The Theater of Terrence McNally.”