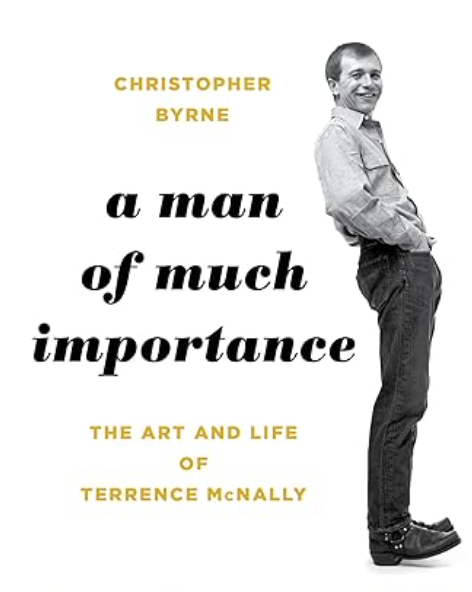

A MAN OF MUCH IMPORTANCE

A MAN OF MUCH IMPORTANCE

The Art and Life of Terrence McNally

by Christopher Byrne

Applause Theatre and Cinema Books 378 pages, $36.95.

MUCH TO THE IRE of the gay press, Terrence McNally (1938–2020) resisted being called a “gay playwright.” Arguing that the term was “ghettoizing,” he protested on more than one occasion that “I’ll accept the label of ‘gay playwright’ only when Arthur Miller is routinely referred to as a straight playwright.” Yet it is difficult to think of another playwright who has represented gay life as fully as McNally, or who has done more to advance gay rights, including marriage equality and support for people with AIDS.

From the start of his career, McNally dared audiences to reconsider what they thought of homosexuality. Fully four years before Stonewall, his first Broadway play, And Things That Go Bump in the Night (1964), offered the first unabashedly gay character who is neither a neurotic nor a predator. Ten years later, in The Ritz, he not only dared to set a riotous farce in a gay bathhouse with actors dressed only in skimpy towels, but made a running sight gag out of the shocked expressions on the faces of heterosexual interlopers who inadvertently stumble upon the group sexual activities occurring in the steamroom. At the height of the AIDS epidemic, when people were suddenly terrified of physical contact, he depicted one character tenderly sucking the blood from another person’s cut finger in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (1987), dramatizing the simple reality that we die, not physically because we’ve had sex with another person, but emotionally when we’re too frightened to risk life-enhancing intimacy.

McNally’s plays rarely failed to arouse controversy over their gay content, most infamously when, in Corpus Christi (1998), he retold the life of Jesus Christ in terms of a gay teenager’s coming of age in 1950s Texas, turning the marriage feast at Cana into an argument for same-sex marriage, and the healing of a leper into compassion for a person with AIDS. McNally was traduced by religious conservatives in the tabloid press, the theater was forced to install metal detectors to protect theatergoers against bomb threats, and a fatwa (still in effect when McNally died more than twenty years later) was issued against the playwright by the Muslim Defenders of the Prophet Jesus. Homophobic critics ridiculed his celebration of gay men’s love of opera divas in The Lisbon Traviata (1989) and of silver screen goddesses in Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993), and audiences gasped at his use of full-frontal nudity in Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994) to explore the bonds that connect gay men. Two late period plays—Some Men (2007) and Mothers and Sons (2014)—movingly chronicled the changes in gay life from the 1920s to the present day and dramatized the homophobia, both external and internalized, that diminishes gay life.

Raymond-Jean Frontain’s most recent book is Conversations with Terrence McNally.