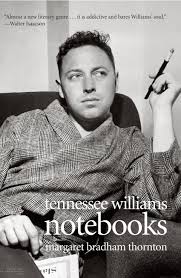

Notebooks

Notebooks

by Tennessee Williams

Margaret Bradham Thornton, editor

Yale University Press, 828 pages, $40

ON AUGUST 2, 1936, at the age of 25, Thomas Lanier Williams confided to his notebook: “I wish I loved somebody very dearly besides myself—.” Thus, early on, Tennessee Williams set the tone of this remarkable, disturbing, often repellent and unsavory record of his life. What strikes a reader here is the extraordinary self-absorption as well as the self-awareness of the remark. There’s nothing I can say about the character of Williams that emerges from the 45 years covered in the Notebooks that isn’t already admitted by the author himself: “I am certainly a damned pessimist or a nervous wreck or something”; “spirits still low but no crisis”; “tired old maid”; “[I am] my only ardent lover (though a spiteful and cruel one)”; “I am not exactly the world’s most tranquil person.”

He was less likely to accept the label of hypochondriac, though that characteristic is omnipresent. It became a sort of badge of rebellion to refuse to accept each single doctor’s verdict—that there was nothing ever substantially wrong with his physical health. Bathetically, notwithstanding the strain on his heart from all his worrying about his heart, Williams would die by choking on the cap of an eye-drop bottle. The body throughout was as likely to dominate as the mind in Williams’ self-evaluation—and it is rarely comfortable or pretty: “(Just spat up some bloody mucous).”