IN AUGUST, 1921, an article by Johnny O’Connor ran in the Dramatic Mirror celebrating drag star Julian Eltinge’s return to the stage as a headliner. O’Connor wrote: “For years he has stood out in the vaudeville ‘Who’s Who’ as the peer of female impersonators principally because of his stunning appearance in feminine clothes and secondly because of his ability, his voice, and all the other essentials that make up the perfect man-woman.” The latter phrase is an apt description of the art that Julian Eltinge created, for he embodied both sexes so fully and convincingly that it was difficult to point to where one ended and the other began.

Despite the high praise that he garnered and his place as a giant in the history of drag, Julian Eltinge is not well known anymore. At his height, he was one of the most famous and popular actors in America, performing to sellout crowds from Boston to Los Angeles.

Praised as hypermasculine off-stage and delicately feminine on, his two sides seemed to negate each other sexually, and he displayed an ethereal asexuality. Women—his most loyal following—appreciated the extreme control of his performance at a time of increasing hostility toward performances involving sexuality and gender.

Eltinge existed in a liminal zone between familiar roles, defying definition and categorization. Consequently, it is difficult to place him as a performer. What exactly was Julian Eltinge as a phenomenon? I contend that he was much more than an early “drag star” and was instead a gender-bending magician keen on dazzling an audience with a complex illusion that was oddly devoid of sexual undertones. Julian Eltinge’s drag was so good that he rendered the questions of gender almost irrelevant. The magic of this transformation was the essence of the show.

His early career provides some clues to the development of his taste for dragging that would make him famous. The seeds of the Eltinge magic act were sown early on. He was born in Newtonville, Massachusetts, as William Julian Dalton on May 14, 1881. The son of a mining executive, Dalton was moved around the West as a child, spending his formative years in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Montana. Eltinge liked to claim that his first taste of drag came with performances in Harvard University’s Hasty Pudding Club productions; but those stories seem to be hyperbole at best, as he never in fact attended Harvard. His first major foray into theatre came in February, 1900, when he appeared in Boston at the Tremont Theatre in Malady and the Musketeer and then with Robert Barnet in Miss Simplicity. Following these successes, he changed his name to Julian Eltinge after a childhood friend in Montana.

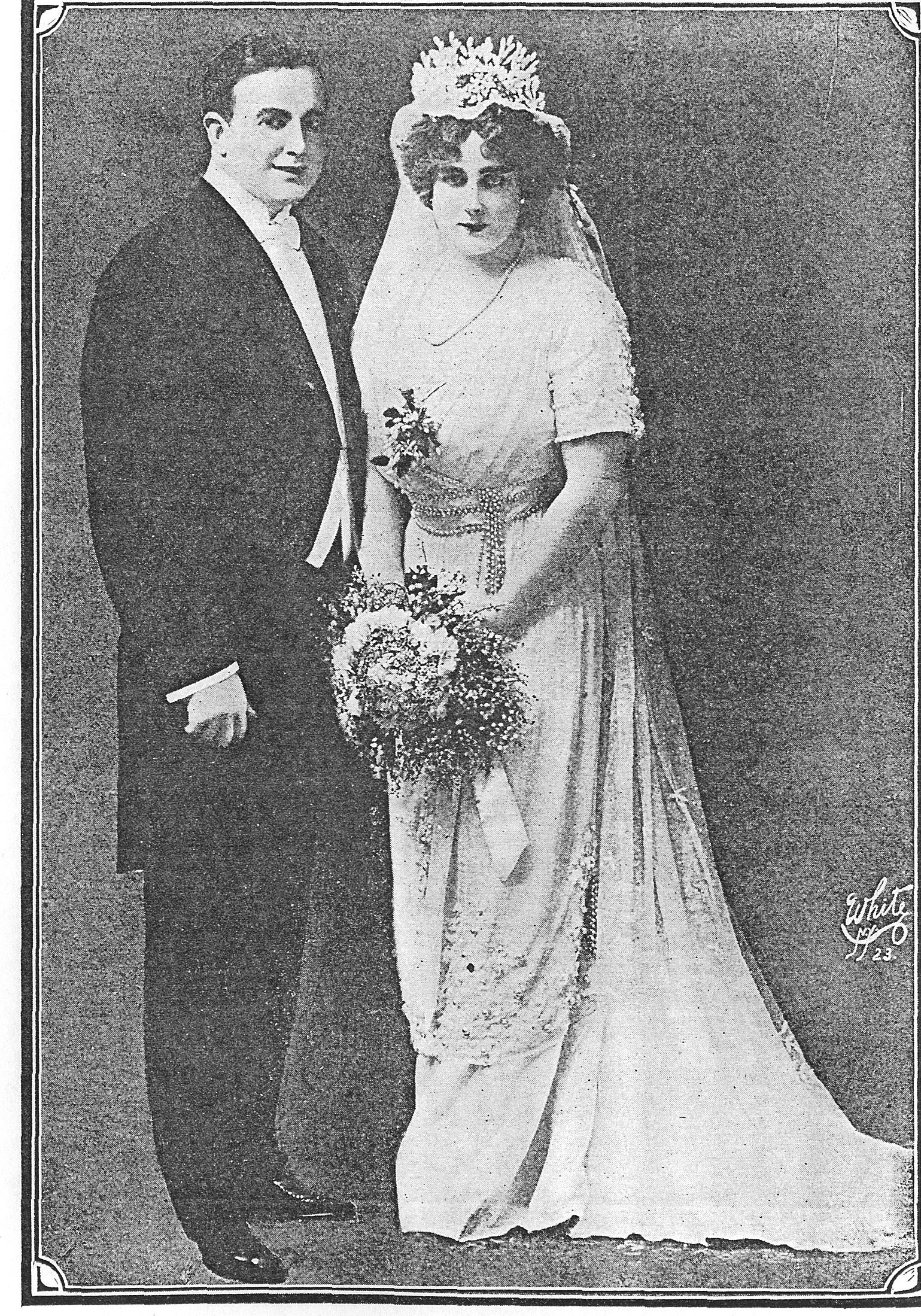

In 1904, producer E. E. Rice brought Julian to New York City to perform in Mr. Wix of Wickham. His star quickly rose with his vaudeville success and gave Eltinge the chance to play many cross-dressing roles, including performances in blackface, as a Spanish dancer, and as blushing brides. Indeed, his experience with multiple transformation-style roles bolsters the case for his pedigree as an illusionist more than as a drag star. True fame hit in 1911 when Eltinge was able to put his vaudeville experience to use in an early motion picture, The Fascinating Widow, where he established the “accidental drag” that would become his forte. It was the rough sketch developed in The Fascinating Widow that would stay with Eltinge throughout his movie career in performances of Crinoline Girl (1914), Cousin Lucy (1915), and The Elusive Lady (1920). In each case, the Eltinge character would be forced to dress as a woman in order to pull off some ruse or reverse a terrible mistake. Off-stage, however, he took great pains to insist that drag was a dreary obligation that was forced upon him by necessity. His PR people insisted that he was most definitely a man, forced to make a living with cross-dressing performances. Be that as it may, in those moments when he was a woman, his authenticity was said to be astonishing.

Eltinge’s drag, it should be noted, was very different from the 19th-century “dame” performers, such as Dan Leno, who excelled at creating a character that was in full possession of his masculinity. Illusion was not the goal, as the cross-dressing dame did not assume a woman’s behavior; indeed, the Dame’s hardly veiled masculinity was a major part of the fun. The dame was overtly sexual, and it was always clear that the performer was aware that he was a man in women’s clothes. The dame was an object of ridicule in a way that Eltinge was not. By the same token, the “glamour drag” that we see today with its exaggerated makeup, pearls, and pumps is a far cry from Eltinge’s controlled and respectable women.

But if an audience was tempted to cast moral aspersions on Eltinge, it seems the performer may have been able to rest on the publicly assumed notion that drag and gender switching were more akin to magic than to sexual deviance. Cultural historian Peter Farrer (1996) points to turn-of-the-century literature, such as Mayfair (1907), An Exchange of Souls (1911), and A Change of Sex (1911), as examples of books that employed hypnotic and magical powers to effect a change of gender. These writings illustrated soul changes such that male souls were magically, for a time, trapped in female bodies. By eliminating any hint of eroticism and creating a sense of the spiritual, the performance of this change could be appreciated in a way that was not seen as terribly nefarious. Indeed, culpability for the change could be left to spiritual forces and the performer could be excused for his or her little problem. Still, this spiritualized possession may have been seen as dangerous in its lack of a controlling mechanism. If an audience saw gender change as spiritual possession, in Eltinge’s case at least they were apparently not too ill at ease. On the one hand he was able to undergo a magical transformation or possession, but off-stage he was presented as being in full control of his masculinity.

It was through his insistence on precision and science that Eltinge bridged this delicate gap. By all accounts, Eltinge worked hard to understand the physiology and psychology of gender transformation, devoting himself to extensive research on the female form and psyche. In 1913, he wrote an article for The Theatre Magazine, “How I Portray a Woman on the Stage,” that outlined the steps he took to accomplish this feat: “The hands are of greatest importance in my impersonation, for they must be made to look quite feminine. … The size of the hands can apparently be decreased by the way in which they are held. … The first rule is never to allow the breadth across the back of the hands to be seen so that the narrowest portion, for instance, the thumb and forefinger or the little finger, will show.”

Accounts of his careful performance back up this idea of magical sex change. There was an incredible truth in illusion that Julian Eltinge perfected. “‘I’ll never forget the first time I saw him,’ recalled a vaudeville prop man of an Eltinge performance: ‘I couldn’t believe it was a man. He was the most beautiful woman I ever saw on Keith’s stage and that includes Lilian Russell and Ethel Barrymore and all the rest’” (Hamilton, 1993). By this and other accounts, it seems that audiences, especially female audiences, were willing to enjoy the theatrics of the show without extensive questioning of the performer’s morality.

To complete the illusion, Julian Eltinge had to go to great lengths to develop an off-stage persona that would counter his on-stage alter ego. To accomplish this, he launched a career-long attack on his would-be detractors, proclaiming his masculinity to the media before they had the opportunity to color him an effete. Consider the splashy datelines from newspapers of the era: “Eltinge Hurt in Collision”; “Julian Eltinge Whips A Critic in Pittsburg”; “Eltinge Wins Battle at Sea: But Swordfish Causes Injuries to Impersonator” (Harvard Theatre Collection). The fish battle was elaborated with the following commentary: “[The 190-pound] marlin got in several rapier-like thrusts which caused the famed female impersonator to undergo an intestinal operation.” The articles about Eltinge in general were so laced with masculine rhetoric as to read like propaganda coming from the great illusionist himself, as indeed it was. Reports abound that Eltinge visited and befriended columnists from local newspapers in the towns and cities that he visited, ensuring that his manly exploits would be covered positively in the papers. An account of Eltinge in an bar fight was as common as a review of one of his performances. One publication proclaimed, “Julian Eltinge Isn’t Effeminate When He Gets His Corsets Off,” and went on to report: “This is Julian D. Eltinge, a handsome, healthy young man, filled with the joy of life, bubbling over with spirits, a strong young athlete who covered right garden for the Harvard baseball team” (Hamilton, 1993).

Julian Eltinge’s manipulation of the press is nicely captured in an interview with Variety in which he denied beating up a man in San Francisco who called him a “sissie.” The magazine quoted him as saying, “I didn’t thrash a man. What would be the use? If I tried to thrash every one who made remarks I would have a perpetually sprained wrist and bruised knuckles” (Variety, 1/6/08). News of Eltinge’s exploits hit the wires, gossip columnists chattered—and then the impersonator denied the whole thing. It was a move that kept him firmly situated in a sexual no man’s land, a place where he could negate his gender bending in a way and firmly appeal to his largely middle-aged female audience by being manly as well as a gentleman.

It is precisely the delicate physical placement of Julian Eltinge, both in writing and in iconography, that may have cemented his popularity and heightened his magic. An unidentified clipping from the Harvard Theatre Collection presents a cartoon of Eltinge preparing for the stage. It shows his dresser Shima, himself a sort of star for being the man who transformed Eltinge, helping the cross-dresser with his corset. Shima is shown small in contrast to the heavy-set Eltinge, emphasizing the impersonator’s masculinity and the difficulty of the transformation. Every indication in the drawing suggests that the process of squeezing into the corset is one that is taxing and unpleasant. He huffs and puffs as his little assistant grapples with his girth. The caption underscores this point: “The little Japanese chief’s duty is to pull the corset strings until the 38-inch Eltinge waist comes down to feminine requirements. The reason Shima carries the butcher knife is that sometimes the strain under which Eltinge labors while masquerading as a woman in corsets becomes too great and it is necessary to get out of his ‘harness’ before he faints.”

The presence of Shima is important in further establishing Eltinge’s distance from the character he created. With this cartoon the magician lets his audience in on his secrets. Here, he was able to show that this was not a case of possession but rather a precise and complicated art. He could also demonstrate that he didn’t like cross-dressing, and endured the transformation with grim resignation. Here is Shima, virtually forcing Eltinge to carry out his deception, further diminishing his culpability. Rather than being a servant to a female alter ego, Eltinge is a servant of his paying audience. But just in case there is any concern, a butcher knife becomes an apt addition to the selling of the performer’s masculinity. It provides emergency relief if the femininity overtakes the performer. Thus all drastic eventualities or misconceptions have been considered.

The selling of Julian Eltinge allowed him to be more than one person. If he were truly a performer of magic, as I believe he was, he had to walk a precarious line. The distinction between the man and his female alter ego needed to be a sharp one to counteract hostility toward effeminacy. More importantly, the split between his two selves was in fact the cornerstone of his magic act. The more manly he was in “reality,” the greater the transformation and thus the greater the performance.

And it appears that his performances were great. His impersonations were in fact so convincing that audiences might have forgotten for a time that they were watching a biological male. When he was forced to perform out of drag later in his career due to local restrictions, he was a disappointment. At the very least, he became a man inextricably linked to the women he played. An image in his self-published magazine succinctly shows this. The “male” Julian looks off in the distance while the “female” Julian gazes down at the viewer. The two of them, for a time, found a middle space between two separate light sources and successfully hid in each other’s shadow.

References

Farrer, Peter. “120 Years of Male Cross-Dressing and Sex-Changing in English and American Literature,” in Blending Genders: Social Aspects of Cross-Dressing and Sex-Changing, Richard Ekins and Dave King, eds. 1996.

Hamilton, Marybeth. “Female Impersonation and Mae West” (in Crossing the Stage: Controversies on Cross-Dressing. ed. Leslie Ferris. Routledge, 1993).