EIGHTY YEARS AGO, The Well of Loneliness was condemned by the English courts as an obscene libel and “burned in the King’s furnace.” The book was indicted and censored solely because of its lesbian theme, for its prose has no spice or sleaze at all. Nothinsd=-g very sexy goes on in it. “She kissed her full on the lips” and “That night they were not divided” are as hot as its descriptions of lesbian lovemaking get.

Before the book was banned, reviewers praised its courage and criticized its solemnity and tendentiousness. None of them found it offensive. But the British government regarded the subject matter as inadmissible in fiction. To publish a book about lesbianism, they said, would blight society’s morals and corrupt the young. Sir Robert Wallace, chairman of the court that censored the book, said it was “more subtle, demoralizing, corrosive and corruptive than anything ever written.” Summonses were issued against the publisher, Jonathan Cape, and the distributor, Leopold Hill. They were commanded to appear at Bow Street Court and “show cause why the said obscene book should not be destroyed.”

An extraordinary trial ensued. It showed up the contempt and outrage of the male establishment provoked by a reference to passion between women. At root, it was not Radclyffe Hall’s book that was on trial; it was her prosecutors’—or, as she called them, her persecutors’—attitude toward lesbianism. They thought it disgusting and they prejudged the case; the defense didn’t have a chance. The government and the judiciary connived to secure a conviction and ban the book. The Home Secretary, the Lord Chancellor, the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Chief Magistrate, and the Attorney General all manipulated the procedures of law and disallowed any process, such as a trial by jury or a hearing of evidence and expert opinions, that might have served the interests of the defendants.

Radclyffe Hall was 48 when The Well of Loneliness was banned. She and Una Troubridge, who left her husband Admiral Sir Ernest Troubridge for Radclyffe, had lived together as a married couple for a decade. In many ways Radclyffe Hall was of the establishment that condemned her. She was right-wing, a patriot, and a mainstay of the Catholic Church to which she gave a great deal of money. She owned a large London house, employed a liveried chauffeur, a secretary, and resident staff. Her clothes and manners asserted masculine authority. She wore neckties, a monocle, and diamond and sapphire cufflinks, and had her hair barbered fortnightly. Order, power, and control she perceived as masculine qualities, and she disliked doing business with women. Radclyffe was a member of the PEN club and a speaker at literary luncheons; she and Una were seen on opening night of all the West End shows. When city life lost its appeal, they moved to her country house in Rye in Kent. Radclyffe rode horses, bred dachshunds and won prizes at the major dog shows. She took her holidays in Italy and on the Riviera, sailed the Channel in a first-class cabin, and had the best suite in all the grand hotels. If men crossed her, she sued them in the (male) courts. When her watch gained a minute and a half in four weeks, she returned it for its imprecision.

It bewildered her to be branded obscene, corrupt, and depraved and to be indicted by the political party that she supported and the social class to which she felt she belonged. She coped badly with such calumny. It fed her fantasy of herself as a martyr on a par with Christ, and it made her ill. After the banning of her book, she vowed never again to live in England, and she never recovered her confidence as a writer.

Her hopes had been high for her “Stephen” novel, as she at first titled it. She wanted it read by schoolteachers, welfare workers, doctors, psychologists, and parents. She viewed it as a pioneer work with a threefold purpose, which she summed up as follows:

To encourage inverts to face up to a hostile world in their true colors and this with dignity and courage.

To spur all classes of inverts to make good through hard work, faithful and loyal attachments and sober and useful living.

To bring normal men and women of good will to a fuller and more tolerant understanding of the inverted.

She described herself as an experienced novelist “who was actually one of the people about whom she was writing.” These people were a “third sex,” men trapped in women’s bodies, she explained. Because she was dyslexic—her spelling was extraordinary—she found reading a struggle, so Una would read aloud to her from Studies in the Psychology of Sex, by Havelock Ellis, and from Psychopathia Sexualis, by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. With disconcerting ease, Hall embraced their contentious theories about “congenital sexual inversion.” She took bits of their writing that appealed to her, mixed these with Catholicism, spiritualism—she was a member of the Society for Psychical Research—and oddball ideas on endocrinology, and came up with a theory of lesbian identity that has startled and dismayed readers of her classic novel down through the decades.

The Well of Loneliness fared better in the United States than in Britain. Covici Friede published the book in New York. The Society for the Suppression of Vice then complained about it, and Donald Friede was charged in February 1929 with “committing the offense of violating Section 1141 of the Penal Code by selling an obscene book.” His lawyer, Morris Ernst, brought to the courtroom commonsense and much-needed sense of humor. The basis of his defense was America’s constitutional right to freedom of speech. To suppress The Well of Loneliness because of its theme, he argued, would “prevent the proper enlightenment of the public on an important social problem” and could have the collateral effect of condoning the suppression of hundreds of other works of literature. Who, he asked, should or could determine the dangerous social consequences of one subject rather than another? Would the “unorthodox emotional complications” of The Well of Loneliness cause more havoc than the sadism in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, abortion in The American Tragedy, the adulteries in contemporary fiction, or the murders, robberies, and violence in crime novels?

What’s more, he averred, Miss Radclyffe Hall was an eminent British novelist. She was the recipient of prestigious literary prizes. It was the task of courts to suppress pornography and punish “purveyors of filth surreptitiously distributed,” not to ban literary works by acclaimed authors. The Well of Loneliness had moral fervor, social significance and integrity of intention. It invited discussion and the exchange of ideas. It was a long book that took time to read. “No child, no moral defective, no impressionable seeker after prurient details would ever get far.”

The obscenity charge was not upheld in the U.S. court. Covici Friede brought out a victory edition and advertised it as “the most controversial book of the century. Suppressed in England and vindicated by an American court.” Orders from bookshops poured in, translation rights were acquired, and money was made. Una noted in her diary the book’s ever-spiraling sales. Radclyffe Hall received a royalty check for $64,000—an enormous sum in those days—and an avalanche of letters. The book’s place in literature was assured. So was her fame, though it was not the sort of fame she had wanted. She felt degraded by the legal process and tainted by her notoriety.

Had the book’s heroine, Stephen Gordon, been a man, The Well of Loneliness might have passed into oblivion as an unremarkable piece of period fiction. Radclyffe Hall was no stylist. She disliked modernist innovations in literature and art. Devotional paintings, English landscapes, and portraits of her ancestors adorned the walls of her houses. She shunned the modernist heresies of Edith Sitwell, Hilda Doolittle, and Gertrude Stein. The prose in all her books is lofty and old-fashioned. She invokes “the Lord” with discomfiting frequency, and uses biblical pronouncements and words like “betoken” and “hath.” Virginia Woolf found The Well of Loneliness unreadable. “The dullness of the book is such that any indecency may lurk there—one simply can’t keep one’s eyes on the page,” she wrote in November 1928. Orlando, her own virtuoso novel, was published that year to resounding praise. The book is about Vita Sackville-West, to whom it is dedicated and with whom Hall was, in a way, in love, but its lesbian allusions were too ethereal and fantastic to invite scrutiny by the Home Secretary. Hall’s subversiveness was that she dared to change pronouns, to write “she [not he]kissed her full on the lips.” Where other writers concealed themselves behind allusion and romans à clef, Hall spoke out.

The journalist Janet Flanner called The Well of Loneliness a rather innocent and confused book. In a more adult society, she said, it would have paved the way for other books on the same subject, books that reflected greater diversity. The possibility of such books was lost when lesbianism in literature was outlawed. If books are suppressed, the complexity of their subject matter is stultified. For decades, the disparagement and censorship of

Readers of The Well of Loneliness were and continue to be provoked by it. It has in it elements of autobiography, religious parable, social propaganda, psychiatric case history, and Mills & Boon romance. “Lesbian” was not a word used by Radclyffe Hall, and no title could be less gay than The Well of Loneliness, which invited spoofs with titles like The Sink of Solitude. It now features in countless dissertations and theses on censorship, sexual politics, gender dysfunction, and lesbian identity. The British government feared and suppressed the book. Feminists through the years have caviled at its patriarchal assumptions. Lesbians have objected to its depiction of them as aberrations, ersatz men, and unfortunates. Students of literature have analyzed how Radclyffe Hall actually deconstructed the theories she purported to uphold.

Because of its theme, The Well of Loneliness unleashed bigotry and hypocrisy. Eighty years on, it is hard to believe that any reader has been corrupted by it. No self-respecting lesbian could want to emulate the gloom of Stephen Gordon’s failed love life. Society now refers more-or-less breezily to lesbians and gays as ordinary citizens, and the focus has shifted from breaking silence to issues of equality, expression, and lifestyle. But it was and remains a landmark publication, a pivotal work. Despite its naïveté, it survives in its own right. Its courage still calls out. Acceptance is never entrenched and can easily be pushed aside. The Well of Loneliness still invites a response from its readers to the tensions of being outside the norm—tensions painfully felt by its hero, poor Stephen Gordon.

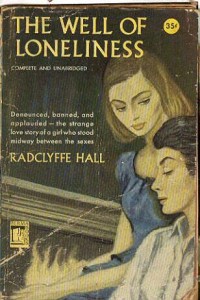

The three cover illustrations tell a story: Pictured are three of the many editions of The Well of Loneliness to be pubished over eighty years. In order: the original 1928 cover; a 1951 paperback edition; the author’s 1998 edition.

Diana Souhami is the author of The Trials of Radclyffe Hall (1998). Her latest book is Coconut Chaos: Pitcairn, Mutiny and a Seduction at Sea (2007).