Classical Nudes and the Making of Queer History

Curated by Jonathan David Katz

Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art

THIS AMBITIOUS EXHIBITION, Classical Nudes and the Making of Queer History, sets out to show how the Greek depiction of gods in their natural state, naked but for the tools and accessories of their trade, gave queer sensibility’s homoerotic desire a vehicle for expression, a vehicle with historical cachet. The naked figure of the Greeks was transformed into the historic nude and, as such, became respectable in the more prudish Judeo-Christian world. The exhibition also shows how a queer sensibility either surfaces or goes underground as it travels through Western cultural history. More importantly, it shows that this sensibility is integral to that history as we rush into the 21st century and perhaps move closer to the natural state of Greek society, where it was an unnamed and normal state of being.

Clearly the Greeks were not hung up on the homoerotic image, or saw same-sex love as a moral failure, or even identified it as a sexual orientation. All heroic depictions of gods, demigods, heroes, and athletes were as naked bodies except for the accessories they wore to represent the realm they ruled or the feat they performed: helmets, shields, boots, garlands, laurels, disks, and spears. The Centaur and the Lapith from the 5th century BCE shows an encounter not between two enemies but between two lovers. The Lapith’s chokehold is not an aggressive one but rather passive to the erotic probing of the Centaur’s mouth. The Lapith’s face shows no pain but rather curiosity if not entrancement.

The Romans continued this Greek tradition in the representations of their gods and heroes, and did so until Christianity began its systematic suppression of the pagan. The anonymous Imperial Roman Male Torso from the 1st century CE is a sinuous fragment of what was perhaps an Apollo that expresses an open sensuality and ease which is attractive and inviting, opening our eyes to its fleshy soft curves, triggering desire with nonliving stone. But as Rome succumbed to the Dark Ages and feudal ignorance, the nude body could only be depicted in the context of crucifixion or bloodletting martyrdom, with sex hidden behind a loincloth (or perhaps a fig leaf, in the case of Adam after the Fall).

When classical philosophy and culture re-emerged in the Renaissance, the pleasures of the world returned as the center of artistic interest. The Story of Diana and Actæon (tempera on panel, ca. 1440), attributed to the Italian Paolo Schiavo, shows the naked goddess Diana being shielded by her equally naked nymphs from the eyes of the hunter Actæon, who’s transformed into a deer by the goddess and hunted down by his own dogs in a case of mistaken identity. Dürer’s woodcut The Men’s Bath from 1498 shows a group of nearly naked men enjoying the pleasures of life. Nearly naked is the key here, as what’s covered is made more prominent by its various positions in the composition, creating bawdy visual puns.

The nude became intrinsic to art in the Renaissance, symbolizing and celebrating earthly pleasure and even hidden sexual desires. Thus by 1650 it was possible for an unknown artist to draw a somewhat deformed but very muscular faun, twisted to show both beautifully rendered muscular buttocks at their most attractive angle and an impossibly elongated thigh. Here the artist clearly lusts for that sensual derrière even as he carefully draws the small tail that renders it a mythical creature rather than a man.

If the Reformation put a damper on matters of the flesh, the Enlightenment brought the naked body back into view, albeit masked in historical archetypes. Thus Henry Fuseli’s The Rape of Ganymede, a lithograph from 1804, shows the shepherd Ganymede as a floating youth spilling mead from the cup he holds, being gently caressed on the face by a muscular but equally youthful Zeus, whose sex is scarcely concealed by the flowing, semitransparent Olympian fabric floating around him.

Female deities never achieved the full nakedness of their male counterparts, starting in ancient Greece. Their sexual organs were traditionally hidden from view, unlike the male penis, leaving their bare breasts to mark their gender. The 1865 pen-and-ink drawing by English artist Simeon Solomon Erinna Taken from Sappho shows three fully robed figures save one exposed breast on Erinna, who’s being taken from Sappho by a male youth. Sappho looks longingly at her unfaithful lover, who sits on the same long bench accepting her seducer’s embrace. The taboo on full female nudity was finally broken in the late 19th century, as seen in Florine Stettheimer’s Nude Study, Standing with Hands Clasped (ca. 1890’s), featuring a nude female with blazing red pubic hair at the very center of the work. Here womanhood is exposed and presented as an object of study, but there’s little doubt that sexual desire, brushstroke by brushstroke, delicately rendered it.

By this time photography was making the scene, and the nude could now be captured as opposed to rendered. An 1883 photograph of Thomas Eakins and J. Laurie Wallace (a male) shows the older teacher and younger student naked by the water’s edge. The photographs by Wilhelm von Gloeden from the 1900’s show Greek youths in Arcadian settings in full, unashamed nakedness except for the laurels and headbands adorning their heads. Here one sees German Romanticism’s embrace of the Greek and desire for beautiful boys in a medium that captures a shockingly literal reality. The German Herbert List’s Beneath the Poseidon Temple shows a nude torso dramatically posed by a Greek temple that is perhaps more about Aryan than Greek mythology but certainly celebrates the male body.

In a series of beautiful engravings by the Russian Audrey Arnoff, The Fall of Atlantis (1944), naked youths inhabit a surreal world as demigods, lovingly rendered and possessing voluptuous buttocks. In plate 13, a slim and helmeted youth with a heavy-lidded, demure expression descends a grand staircase as in a Ziegfield production. Here again we see the semitransparent fabric or scarf that slightly obscures his pubic hair while also highlighting its presence. More down-to-earth is the brilliantly colored tempera-on-wood Bar Italia, 1953-55, by Paul Cadmus, where classicism meets the modern demimonde world that he’s so famous for depicting. The stillness of the Roman architecture serves as backdrop for a boisterous scene populated not by demigods but by the common plebs. The characters on this satirical scene are alive with comic narratives as they surround a family of silent and bored American tourists.

Boy Party (1954), by the American artist Jess (a.k.a. Burgess Franklin Collings), again uses a contemporary setting for what is a bacchanal, an orgy of joy but without Bacchus or, with the exception of a few ionic columns, classical allusions. Here lovers slow dance and kiss; a naked boy dances jubilantly in an interracial daisy chain while various groups of lustful boys fuck in the background. This wonderful oil on plywood, a shocking picture for its era, was probably never seen by the public but only by a coterie of close friends; it was the 1950s, after all. But this was also the decade in which Masters and Johnson published their research on sexuality, a prelude to the Sexual Revolution of the ’60s and to the Stonewall riots themselves.

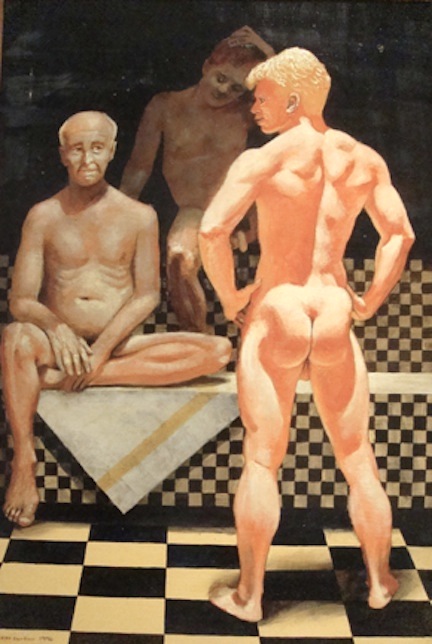

The American artist John Burton Harter’s oil on masonite Bath House Adonis from 1996 depicts a trio of naked men relaxing in a tiled sauna. An older man sits on a towel covering his genitals with his hands crossed over his folded leg, casting an admiring

Oil on masonite.

if slightly puzzled gaze upon the young “Adonis” facing him, arms akimbo. Behind the older man sits a youth with legs wide apart, his bare member in full light and revealed at the center of the composition through the gap between the foreground figure’s arm and body. The latter does not have a conventionally handsome face as the name Adonis would suggest but instead displays a delightfully impish profile as he stands in full light, proudly showing off what we can only assume is an impressive sex organ to go with the dangling testicles that peek out between his separated legs and under those tight buttocks. Harter has liberated the nude from classical mythos by applying the name of Adonis generically to any sexy youth, even one who falls well outside any classical definition of male beauty.

Moving closer to contemporary times, sexuality and gender begin to be explored in a kind of clinical, documentary way, as desire and identity become vague while also starkly assertive. American photographer Nan Goldin’s chromogenic print The Back (2011) is a loosely composed grid of images of sculpted, drawn, and photographed male and female backs in various poses. There is no central figure; each fragment exists in its own limited and unconnected space, as in an apartment building where no one knows their neighbor. The Canadian Sunil Gupta’s archival pigment print Untitled #9, from his Sun Series (2010), shows a group of nine men, all naked and well-built, posing as if statues in a Moroccan-themed bathhouse. A toweled figure sits curled up in the center of the gathering but seems not to belong to the posing group, from which he seems alienated.

This is a must-see exhibition with a great catalogue that promises not to exhaust but to delight you and, if you are willing, to enlighten you about queer sensibility’s rightful place in the history of art.

George Queral is an architect and artist living in New York City.

Discussion2 Comments

This is an excellent article about the presence of the gay sensibility in the visual arts throughout the centuries.

I particularly like the photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden which seem both refreshing and innocent today.

I once met a man who had amassed a large collection of these prints, which were eventually destroyed by a home invasion.

He hadn’t really gotten over it.

“Bath House Adonis” rightly restores the supremacy of the voluptuous male derriere.

Like the penis, it is made to be worshipped.

In Art History classes we learn that the artist in his/her unfolding is striking out on achieving a nativity of his own, in that exact moment when total relationship is affirmative of our experience in the outside world and society. It has always been tempting to see the Greeks with a partial understanding of this Nativity of those given to Society, and it’s myths and truths. This is not to say an artist has to resemble a Berdache or a Hjira to express his native and tribal sense of origin. When it is this sense of origin in itself that bring to the individual a personage that demands respect by those whom are given to fair judgment of it’s virtue and vice. While responding to the image with a profundity based on the merits of the act, the creation, and the rendition and depiction of the beauty of life are given solely on it’s own accord.