“WHAT IS an Itkin anyway?” The rhetorical question was put to me as I was sitting in a Manhattan leather bar one summer night in the mid-1970’s. My companion that evening was apparently a pretty boy in full leather, actually an attractive young woman by the name of Dusty Verity, a former circus performer who had written me a fan letter the previous week and had now turned up at the Eagle’s Nest in very becoming drag. We were discussing mutual acquaintances and soon discovered that we both knew the notorious anarchist bishop, Mikhail Itkin. I was one of many names on his mailing list while Dusty was part of his small coterie of gay libbers and radical Christian activists.

It is often forgotten now that the rise of radical gay activism in the 70’s accompanied an upsurge of queer spirituality. The Metropolitan Community Church was founded in the late 60’s by Rev. Troy Perry (a pastor always more politically radical than most of his flock) and soon enjoyed a steady period of growth. Robert B. Clement’s Church of the Beloved Disciple established a flamboyant presence in New York City. The well-known civil rights activist and “coffee-house priest,” Father Malcolm Boyd, author of the best-selling Are You Running with Me, Jesus? (1965), came out of the closet with a bang. And the Rev. Billy Hudson, author of Christian Homosexuality (1970), founded something called the “American Association of Religious Crusaders: A National Interfaith Homophile Association,” though that seems to have vanished without a trace.

It is often forgotten now that the rise of radical gay activism in the 70’s accompanied an upsurge of queer spirituality. The Metropolitan Community Church was founded in the late 60’s by Rev. Troy Perry (a pastor always more politically radical than most of his flock) and soon enjoyed a steady period of growth. Robert B. Clement’s Church of the Beloved Disciple established a flamboyant presence in New York City. The well-known civil rights activist and “coffee-house priest,” Father Malcolm Boyd, author of the best-selling Are You Running with Me, Jesus? (1965), came out of the closet with a bang. And the Rev. Billy Hudson, author of Christian Homosexuality (1970), founded something called the “American Association of Religious Crusaders: A National Interfaith Homophile Association,” though that seems to have vanished without a trace.

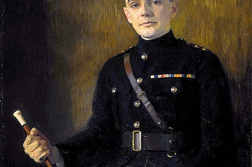

Adding a uniquely anarchic presence to this heady mix was a diminutive leatherguy called Mikhail Francis Augustine Itkin, a Christian anarcho-pacifist, Independent Bishop, and general, all-purpose shit-disturber. Itkin was born Michael Lewis Itkin in New York City on February 7, 1936, of Jewish parents who exposed him to left-wing politics early through former Vice President Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party. At the age of sixteen, Itkin was ordained a minister by the social activist People’s Institute of Applied Religion. Two years later, he was baptized in the Episcopal Church and discovered the Homophile Movement, becoming one of the founders of The League, Inc., which later became the New York Mattachine Society. In 1957, he was ordained into the Eucharistic Catholic Church, the first Christian body in the U.S. to open its ministry to gay people.

Over the years, Itkin founded, or revived, various small groups attempting to develop an egalitarian theology centered on “the androgynous spirit of the universal and indwelling Christ,” emphasizing sexual openness, revolutionary pacifism, and universal human rights, and conducting Old Catholic and Eastern Rite services. Itkin made notable contributions to ecclesiastical history in his writings about the influence of the Jewish Temple on early Christian worship. At various times he was linked with Sufis and radical Mennonites. In the late 60’s, he became one of the first Old Catholic bishops to ordain women, a move that led to a major split in his denomination and the loss of most of its property.

“From the early Fifties,” wrote Toby Marotta in The Politics of Homosexuality (1981), “Itkin had riled homophile leaders on both coasts with talk about radicalism, religion, and the importance of expressing homosexual feelings openly.” In 1969, he was present at the Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village. He wrote and presented the Resolution on Homosexual Rights adopted by the American Sociological Association, the first such resolution adopted by an American scholarly or professional society. The following year, he and others in the San Francisco Gay Liberation Front famously disrupted the American Psychiatric Convention held in that city. In their book Out for Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America, Dudley Clendenin and Adam Nagourney chronicled the event: “One of the most despised and infuriating figures in all of American psychiatry, as far as homosexual activists were then concerned—the author of a 1962 study that suggested that homosexual men were the products of weak fathers and smothering mothers—was scheduled to be on a panel at the [1970] American Psychiatric Convention. Dr. Irving Bieber … was a magnet for protesters, and the Gay Liberation Front decided to be there too. … Konstantin Berlandt wore a bright red dress and a full beard, and he, Gary Alinder and Michael Itkin, among others, haunted the APA sessions, disrupting them with displays of guerilla theater and angry protests form the floor.”

An avid reader of Walt Whitman and his radical English disciple Edward Carpenter, Itkin believed Gay Lib had the potential to fulfill Whitman’s prophetic dream for America. “Gay Liberation,” he wrote in his polemical 1972 essay The Radical Jesus and Gay Consciousness,

is not an organized or monolithic thing. Arising in response to long-felt needs, it consists of many individuals and small groups … cutting across many class and political lines … to whom the life thus far forced upon them is far more to be feared than the penalties to be faced by being open about homosexuality. … We are a minority people struggling to create our own subculture. … The immediate issue is that we must continue to intensify the struggle for Gay freedom now and thus create a new Gay Consciousness.

“Take a moment,” he advised his readers, “to talk to adolescent runaways, youth without homes, street people, Black people, Latin and Indian Americans, the aged, the handicapped, draft resisters, demonstrators for peace, and revolutionaries who rightly feel that the institutional church has betrayed the revolutionary message of the Gospel … which is an outrageous shout of Love and Joy!” For Itkin, Gay Liberation entailed the overcoming of evil by the power of love, and the peaceful creation of a new co-operative community that would be an active force for good in the world.

These ideas place Itkin as part of a radical stream of Gay Liberation that saw itself as spiritual as well as political, and that was influenced by anarchist and libertarian thought as well as by esoteric spirituality. For example, in the early 70’s, the important East Coast newsmagazine Gay was edited by lovers Lige Clarke and Jack Nichols. Nichols had studied in the Baha’i movement and was strongly influenced by Whitman and Carpenter; Clarke was a yoga instructor. Another Carpenterian was scholar/activist John Lauritsen, co-author of The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935); Lauritsen’s Pagan Press published an edition of Carpenter’s Iolaus: An Anthology of Friendship in 1982.

Based on New York’s Upper West Side, the radio broadcaster Bob “Flash” Storm and his partner, artist Ralph Hall, a lanky, sweet-natured hippie with a perverse sense of humor, issued Gay Post, Faggots on Faggotry and Ain’t It Da Truth, brightly colored “gayzines” which they sold or gave away on the street. These proto-zines ran poetry by Allen Ginsberg and Robert Burdick, and covered news and events that other media ignored. The group helped prisoners on Riker’s Island and in the notorious “Tombs” and sponsored the Gaywalk, an alternative to the official Christopher Street Parades. Another anarchist group, the Gay Clone Collective, operated out of Eleanor Roosevelt House at Hunter College.

In Boston, the anarchist-oriented Fag Rag collective published its radical gay paper as well as books such as Arthur Evans’ Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture (1978) and the “Good Gay Poets” series (its name a play on the “Good Gray Poet,” Whitman). Fag Rag’s most prominent figure, Charley Shively, a poet and professor of American Literature, later published two books on Whitman and his lovers and was one of the first to discuss Abraham Lincoln’s bisexuality.

On the West Coast, the Cockettes and the Angels of Light furthered the anarchic tradition of street theater, and Mattachine founder Harry Hay, an initiate into American Indian spirituality, mentored the Radical Faeries. Itkin often acted as the spark connecting all these disparate groups and individuals, the artists and the activists, the old homophiles and the young gay radicals, the spiritual and the political.

I first met Mikhail Itkin through his friend Dusty Verity, in New York City, in the mid-70’s. His reputation had preceded him: he was remembered for his amazing multiple orgasms and his tendency not to return borrowed books. On our first encounter, he was hurrying to a conference and we shared a five minute cab ride, during which he propositioned me, suggesting that we could probably find a convenient corner somewhere for a quickie, presumably during a break in the proceedings. The offer didn’t interest me and when he alighted I continued my ride. He seemed unbothered by my demurral and whenever our paths crossed, he was always talkative and friendly.

Independent bishops have traditionally been known as “itinerant bishops,” but Itkin seemed more of a rushing or whirling variety. A small man of high energy and high spirits, he skittered about like a tiny whirlwind, stirring up controversy. His keen mind seemed overloaded, jumpy, as though some isolated malfunction kept overloading, or jamming, the circuits. His mood swings and uncertain attention span were apparently awarded a medical diagnosis, one which allowed him to draw a small pension as virtually his only source of income (unless one credits the tales of his selling ordinations to nervous clergymen unconvinced of the validity of their offices).

Itkin could provoke people to action without necessarily staying around for the inevitable follow-up. His friend Wayne Dynes commented on his “lack of personal charisma.” This was emphasized by a tendency to scowl unattractively. And he could inspire visceral distaste. In his bitterly funny memoir Dropping Names (2004), novelist Daniel Curzon reviled him as “a self-anointed little bloated toad,” speculating that he probably pissed out of windows.

I once caught a glimpse of the peripatetic bishop as I was walking through the East Village. A street demonstration was in progress—a local protest about housing conditions and squatter evictions. A motley crowd of peaceful protesters faced an armed phalanx of New York’s Finest. In the gap between them was Ralph Hall. Affecting a Groucho Marx crouch, he was approaching the police line, lips pursed, hands outstretched, cooing “Here piggie piggie piggie!” The cops were getting blue-faced and restless. Itkin might well have worried that the whole thing could quickly turn nasty. “You’re a provocateur, Ralph!” he shouted, grinning. “A provocateur!”

In the late 70’s, Itkin moved away from New York permanently and resumed his mission in California. In 1980 he ordained the novelist Marion Zimmer Bradley and her husband, numismatist Walter Breen, the pseudonymous author of Greek Love. Other colleagues included his successor Marcia Herndon, filmmaker Fred Halsted, and journalist Jim Kepner, who preserved some of Itkin’s papers.

Published cheaply by a small, co-operative press, The Radical Jesus and Gay Consciousness is both a political document very much of its time and a spiritual record valid for any time. It is Itkin’s account of his struggle to reconcile the complexities of Christian theology with the spiritual, social, and sexual needs of his own people. A “tough little Jewish kid from the Bronx,” he never ceased trying to reconcile cosmic theology with the pressing necessities of day-to-day life on the street, a leather-jacketed dervish whirling his sacred mission through the bemused crowd.

Bishop Itkin died August 1, 1989, of complications from AIDS. His ashes were scattered in the garden of the Episcopal Church of St. John the Evangelist in San Francisco. In 2002, the Moorish Orthodox Church elevated him to its pantheon of saints.

Ian Young is the author of The Stonewall experiment: A gay psychohistory (Cassell Books, 1995).

Discussion1 Comment

Moira Greyland states that her father, Walter Breen, molested two underage prostitutes, 13-year-old Gregg Howell and 12-year-old Barry Austin, after they were procured for him by a group of predatory clergymen led by Archbishop Mikhail Itkin.