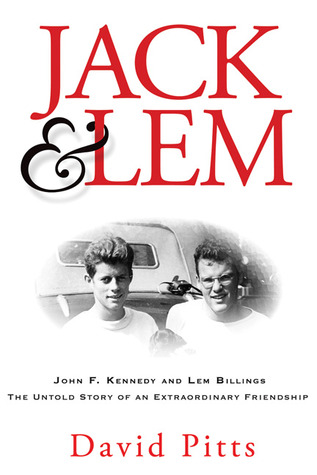

Jack & Lem: The Untold Story of an Extraordinary Friendship, John F. Kennedy and Lem Billings

Jack & Lem: The Untold Story of an Extraordinary Friendship, John F. Kennedy and Lem Billings

by David Pitts

Carroll & Graf. 384 pages, $26.95

THE OLD black-and-white photograph shows two good-looking young men sitting close together on the back bumper of a car, their fingers touching gently as they fondle a dachshund pup. The one with glasses is squinting into the light. Both are smiling at the camera. They appear to be a gay couple with their little dog. They are in fact John F. Kennedy, future president of the United States, and K. LeMoyne Billings, his best friend and intimate companion. “That John Kennedy maintained a deep friendship with a man whom he knew to be gay, and did so in an age of homophobia—at great potential risk to his political career and reputation—is an extraordinary demonstration of loyalty and commitment,” writes David Pitts, author of the first full account of what he characterizes as “a love story unknown to most Americans.” But, he reminds us, “risk avoidance was not part of Jack Kennedy’s DNA.”

Young Jack met the boy who was to be his lifelong best friend when they were prep school classmates together at Choate. Jack, the son of a self-made Boston Irish millionaire, was a wealthy, bright, good-looking boy with a wicked sense of fun. He was also skinny, sickly, and frail, continually falling ill and being subjected to various medical tests. Lem Billings, from a distinguished old American Protestant family, was taller, bigger, stronger, with a high-pitched voice and a loud laugh. They shared an insatiable intellectual curiosity, a robust sense of humor, and a disdain for petty rules. Within days of meeting, they were best friends, and their censorious housemaster was grinding his teeth over their “silly giggling” hijinks in the showers and their annoyingly “inseparable companionship.” Lem soon became part of Jack’s family and a huge favorite of both Kennedy parents.

At Choate, boys who were interested in sexual involvement with other boys were courteous and discreet, writing notes on toilet paper so they could be easily swallowed or flushed. Early on in their friendship, Lem sent Jack such a note and Jack replied in their usual jocular way, adding in parentheses, “Please don’t write to me on toilet paper any more. I’m not that kind of boy.” With that out of the way, their relationship continued essentially unchanged until JFK’s assassination thirty years later. When circumstances determined that Lem and Jack would attend different colleges, they kept in touch by telegram, sometimes dispatching up to seven a day, and they spent their weekends together in New York City.

Throughout his life, Jack Kennedy coped with incapacity and severe pain from his various ailments—Addison’s disease, colitis, hepatitis, malaria, recurring infections, and a bad back. Lem knew how to help Jack with all his old problems—and keep them confidential. Jack’s medical tribulations are a frequent subject of his amusing early letters to Lem, some of which are quoted in Nigel Hamilton’s 1992 book JFK: Reckless Youth. “Nobody is able to figure out what’s wrong with me,” he wrote from hospital. “They give me enemas till it comes out like drinking water which they all take a sip of,” he wrote. “Then surrounded by nurses the doctor first stuck his finger up my ass. I just blushed because you know how it is. He wiggled it suggestively and I rolled ’em in the aisles by saying ‘you have a good motion’!!”

Jack’s letters to Lem are full of endearments and jokey deprecations; he addresses Lem alternately as “you slimy fuck,” “you filthy-minded shit,” “my sweet,” and “You bitch!” Sometimes he just tells him, “You’re swell!” Billings was “a big, attractive guy who told wonderful stories and cheered everybody up,” according to Pitts. Many photos show him roaring with laughter. Jack particularly enjoyed Lem’s comic songs, his favorite being Lem’s impersonation of Mae West singing “I’m No Angel”: “Aw come on, let me cling to you like a vine,/ Make that low-down music trickle up your spine./ Baby I can warm you with this love of mine.”

The two friends’ relationship remained essentially unchanged even when Kennedy became president. He offered Billings a choice of administration posts, but Billings, who worked in advertising and was once offered a job as the Marlboro Man, preferred to buy and restore old houses. He stayed frequently in the White House, where he had his own room; only he, the President, and Jackie required no White House pass. He traveled and holidayed regularly with Kennedy, who would often introduce him to foreign dignitaries as “Admiral Billings” or “Undersecretary Billings.”

Jack Kennedy, it seems, was perfectly comfortable around gay people. Another gay friend, aviation adviser Langdon Marvin, recalls a discussion that took place while Kennedy was in the bath, with Sinatra singing “All or Nothing at All” on the record player. And seeing Leonard Bernstein and Igor Stravinsky exchanging kisses on both cheeks at a state dinner, Jack asked, “How about me?”

Although heterosexual, Kennedy’s interest was in sexual conquest rather than in “spending much time with women.” He enjoyed the company of bold, intelligent men who had a good sense of humor. “I just seem to be attracted by men like that,” he said. “Maybe it’s chemical.” He told an aide, “I only got married because I was 37 and people would think I was queer.” When he did marry, his wife got along well with Billings, who sometimes had to explain Jack to Jackie—or vice versa. It’s easy to forget that in JFK’s era, the press was far less intrusive than today. Pitts remarks that Kennedy’s aides “knew that the press would never print a story about the President’s best friend being gay—no more than they would print anything about his extramarital affairs.” Or the precarious state of his health.

The Kennedy-Billings friendship was first explored by Peter Collier and David Horowitz in their 1984 book The Kennedys: An American Drama. Nigel Hamilton’s JFK: Reckless Youth (1995) drew from the extensive correspondence between Kennedy and Billings (some of Jack’s letters to Lem are forty pages long) and Billings’ 815-page oral history at the JFK Library. Now Jack & Lem rounds out the story, adding many vivid details, among them the fact that one of Kennedy’s favorite gifts from Billings, a whale’s-tooth scrimshaw, was buried with him.

After Robert Kennedy’s assassination, Billings became a surrogate father to Bobby Jr. and other Kennedy boys, several of whom have spoken of Billings with great affection. His leadership helped establish the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the John F. Kennedy Library. Senator Ted Kennedy described the friendship between his brother and Billings as “a bond of perfect trust and understanding that served them all their lives.” Eunice Kennedy Shriver is quoted as saying that “President Kennedy was a completely liberated man when he was with Lem.” Another friend remarks of the two men’s relationship, “it was love, and not all love has to be consummated.”

Ian Young’s A Visual History of Gay Pulps is being published in paperback (by Lester, Mason, & Begg) this fall.