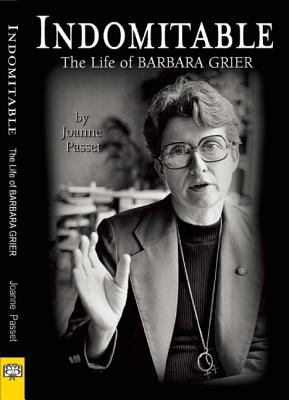

I ndomitable: The Life of Barbara Grier

ndomitable: The Life of Barbara Grier

by Joanne Passet

Bella Books. 384 pages, $28.95

BARBARA GRIER (1933–2011), best known for her role as the publisher at Naiad Press, was at once a complex and single-minded person. She believed that power came from wielding the printed word, and once wrote: “History will do its best to ignore us; we need to do our best to make sure it cannot happen.” When she was young, looking for lesbians in books, she did so with dogged determination. What she found were books in which lesbians were deviant and self-destructive, and always ended up dead or defeated. This is something she was determined to change.

Grier realized she was a lesbian by the time she was twelve. She told her mother, who took it well. When she was sixteen, her mother gave her a copy of The Well of Loneliness. Shortly after graduating from high school in 1951, she was working as a library assistant in the public library, where she met Helen Bennett, who was sixteen years older than Grier. The two became fast friends and then lovers. Bennett was secretive and fearful that people would find out, but Grier believed that most people, even Helen’s parents, understood they were a lesbian couple. They moved to Denver, where Helen attended college and Barbara worked at a clerical job for The Denver Post.

In 1955, the lesbian group the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) was founded by Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, who started to publish a monthly magazine called The Ladder. Grier contributed to The Ladder under a number of pseudonyms, most often as Gene Damon. Her stories and essays had a singular intent: to inform lesbians that they had a long history and a rich culture. As time passed, Grier corresponded with several of the magazine’s readers and writers. Bennett objected, so Grier, without her partner’s knowledge, got a post office box. For years she communicated by mail with lesbians, sometimes developing secret flirtations.

In 1966, the National Organization for Women was founded. From the beginning, DOB leaders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon questioned NOW’s ability to address the concerns of lesbians. Grier questioned DOB’s involvement with NOW, saying: “When we have amalgamated and homogenized and pasteurized ourselves thoroughly, we can become one of the shapeless, formless, meaningless ‘walk alike, talk alike, think alike’ things which now live in this country—and then who will write our poetry, our novels of intensity, who will burn a futile fire, howl at the moon aimlessly?”

In the following year, Grier took the editorship of The Ladder for a short time, but in 1970 the publication separated from DOB. The latter was seen as outdated in a post-Stonewall world, and some members, including Grier and DOB president Rita Laporte, wanted The Ladder to strike out on its own. In a famous incident, Laporte—according to her own testimony—went to DOB headquarters and removed the mailing list, back issues, and some office supplies. While Laporte was physically responsible for the theft, “Barbara willingly took credit for the action because the two women had planned it together.”

In the following year, Grier took the editorship of The Ladder for a short time, but in 1970 the publication separated from DOB. The latter was seen as outdated in a post-Stonewall world, and some members, including Grier and DOB president Rita Laporte, wanted The Ladder to strike out on its own. In a famous incident, Laporte—according to her own testimony—went to DOB headquarters and removed the mailing list, back issues, and some office supplies. While Laporte was physically responsible for the theft, “Barbara willingly took credit for the action because the two women had planned it together.”

In 1967, Barbara Grier met Donna McBride, the woman who would be her partner to the end of her days, in the Kansas City Public Library. In articles that Grier wrote for The Ladder, she proclaimed that lesbians needed to lead exemplary lives and encouraged fidelity. Thus she hesitated to leave Bennett in order to take up with McBride, which she saw as a betrayal. So she delayed. After a great deal of soul-searching and a subtle threat from McBride, she left Bennett.

During Grier’s early days at The Ladder, she exchanged letters with lesbian novelist Jane Rule. Grier told Rule, dishonestly, that she’d published 32 original paperback novels. When Rule shared a poem that her friend had written, the poem mysteriously appeared in the June issue of The Ladder. Rule was furious and said she was ashamed to have her name connected to The Ladder. However, this did not prevent Rule from publishing with Naiad Press, with which she would later republish Desert of the Heart and several original novels.

Naiad started out as a vanity press. The name was chosen by Anyda Marchant, who wrote as “Sarah Aldridge.” Naiad’s first book was Aldridge’s The Latecomer. As president of Naiad in its early years, Marchant loaned Naiad money to cover the cost of typesetting, printing, and binding, and then repaid herself from income generated by the sale of the books. The press eventually published on a “cost recovery” basis. Naiad, rather than Marchant, would cover the cost of bringing a book out, and the author would get royalties after expenses were met. Grier and McBride worked without pay until October, 1981, when Grier became Naiad’s first full-time employee. A year later, McBride became the second. By then they had moved the operation to Tallassee, Florida.

Grier was a good promoter and worked hard to get Naiad into bookstores. She distributed review copies of new releases to prospective reviewers. In the beginning, she used volunteer labor to handle the typing of manuscripts and invoices. She admitted to having “an abrupt personality,” and many volunteers didn’t stay long because of her callous treatment of both workers and writers. Lee Lynch, a writer who published with The Ladder and then became a Naiad author, said: “She praised with one hand and bullied with the other, intimidating both the meek and the strong among us.”

Following Naiad’s highly successful publication of Katherine Forrest’s Curious Wine (1983), Forrest joined the company as its senior editor. Soon Grier was acquiring new genres of lesbian literature, including mysteries, Westerns, science fiction, and erotica. Forrest, an award-winning author, went on to publish books of fantasy and a mystery series. In 1995, Forrest left Naiad after clashing with Grier. It started over her desire for a hardback book, which Grier didn’t think the market would support. She finally printed The Beverly Malibu (1989) in hardback; the book won awards, sold well, and was reviewed by The New York Times. But Grier refused to acknowledge its success. Meanwhile, Forrest was offered a guaranteed $50,000 a book by Putnam-Berkley and decided to leave Naiad. An alarmed Grier offered to match this advance, but Forrest, tired of the abuse, turned it down. Grier decided to hold Forrest to her contract, which gave Naiad first right of refusal for her next book. Forrest submitted an early novel that had little lesbian interest, and that was that.

Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence (1985) was the book that changed everything. In 1981, at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival two women, Nancy Manahan and Rosemary Curb talked about putting together an academic anthology of writings by nuns who’d left the convent for a lesbian life. In 1983, Naiad sent Manahan and Curb a contract. She assured the women that Naiad would put “an inordinate amount of weight behind” the book. The contract gave Naiad “full exclusive and sole rights” to all things concerning the publication and marketing of the book. Neither Manahan nor Curb realized the frenzy Lesbian Nuns would garner, and they found themselves at the mercy of Grier’s marketing strategies. The first six months after the book came out, Manahan and Curb did more than eighty TV shows and were the subject of more than 200 book reviews and articles. They got hate mail and angry callers to radio talk shows. The Catholic Church denounced the book as indecent. Grier sold excerpts from the book to Forum, a soft-core porn magazine. Some contributors wanted to be excluded, but Grier told them it was too late. Naiad Press and Barbara Grier made hundreds of thousands from Lesbian Nuns, but her peers felt that she had exploited the authors. Grier was lambasted, in Passet’s words, for her “tendency to exaggerate, combined with her quick temper and arrogance.”

Indomitable is well-documented and provides helpful aids to readers: a timeline, end notes, and a useful index. Joanne Passet has done justice to a complex personality who played an indispensable role in the development of lesbian publishing. Barbara Grier loved books and was on a mission to make lesbian-oriented books readily available to their intended readers. Her relentless drive to fulfill this mission led to conflict, which makes for good reading in a biography; but much of the conflict came from Grier’s own shortcomings, which makes her achievement seem bittersweet.

Martha Miller is a Midwestern writer of plays, short fiction, reviews, articles, and novels. Her latest book is Tales from the Levee.

Discussion1 Comment

I remember meeting Barbara back in 1982. It was at the National Womens Studies

Studies Conference in Humboldt, Calif. Our Women’s Studies Director from Sonoma State University, had chosen a few of us to go with her. Our small group of eight led a protest, when the coordinators decided there would not be time for student representatives to speak.. We got our chance to speak. In the middle of this, I struck up a conversation with Barbara, and I told her about a story I was working on. She seemed interested and was kind enough to give me her business card. To my shame, I never sent her my manuscript…..and now she’s gone. I will never forget how attentive and caring she was during our conversation. She never rushed me and made me feel like she was really interested in what I was saying. I actually cried when I heard of her passing.