We have recently returned from a G&LR-sponsored trip to Mexico City, and I’m here to report that it was a great success. Organized by Out Adventures of Toronto, the five-day trip was a banquet of art and archaeology, among other explorations. We traveled out to the vast site of Teotihuacan with its three great pyramids; to the world-class Anthropological Museum with its spectacular Toltec and Zapotec displays; and to the National Palace, home of Diego Rivera’s amazing murals. We also visited the famous “Blue House” where Rivera’s wife, Frida Kahlo, lived and worked for much of her life; and it is this part of the trip that I’ll focus on here, if only because her life and art have a connection to The G&LR’s franchise.

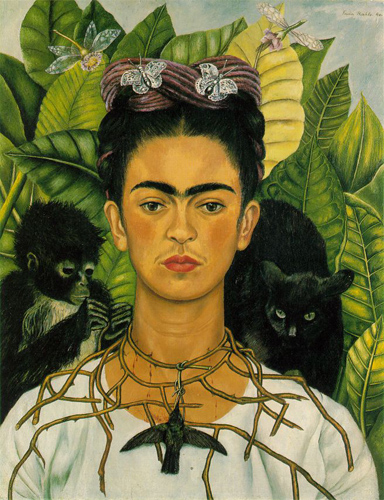

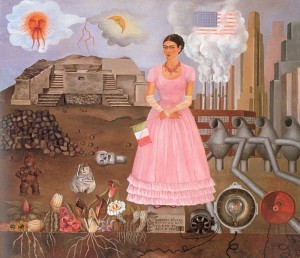

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) is best known for her many self-portraits, 55 in all, which comprise around half of her corpus of paintings. She adopted numerous personae in these works, depicting herself as everything from the creative Earth Mother to a helpless object of medical intervention. What’s striking is the essential sameness of her face from one painting to the next, even as the settings shift drastically from Edenic harmony with nature to vivisected bodies reminiscent of Francis Bacon (well, almost). Even when representing herself as an infant emerging from her mother’s womb, she has her adult face with that indeterminate expression—or the absence of expression, that Sphinx-like neutrality—that she always wears.

She exaggerates the famous unibrow, to be sure, increasing the androgyny of her face. That she is both male and female reinforces that sense of refusing to commit to any one thing. Indeed, it seems inevitable that at some point she would bob her hair and dress in men’s clothing, as indeed she did at a couple of points in her short lifetime—all documented, of course, in the self-portraits from these phases. Her androgyny is an aspect of the facial neutrality, which gives her a kind of universality in that any viewer can identify with the every-person at the center of the canvas, who is typically gazing directly out at the viewer. In this way, Kahlo was able to bring the viewer into her world—and there’s no doubt but that the content of the self-portraits was almost entirely autobiographical—such that we feel her joys and sorrows, even, almost, her physical pain, the result of a crushing trolley accident when she was sixteen.

That Kahlo was bisexual in her personal life seems a logical expression of the fundamental dualism of her personal mythology, which included elements of Native and contemporary Mexican culture, as well as a significant dose of Marxism, a philosophy to which she and Rivera strongly subscribed. It was her avowed mission to incorporate archetypes drawn from Native culture, which she interpreted as strongly dualistic, divided between forces of night and day, moon and sun, female and male. She sometimes appears twice in a single painting, representing both sides of an existential dualism. Kahlo incorporated these Native traditions into her personal mythology in a way that’s reminiscent of Oscar Wilde, dressing the part, looking the part, and acting the part vis-à-vis her sexual partners.

Kahlo’s bisexuality is recorded in both her paintings and her private life. To start with the latter: the evidence is quite strong that when she visited Paris she had an affair with the great Josephine Baker, the African-American dancer and burlesque entertainer who took Paris by storm in the 1930s. She is also reported to have had affairs with American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, Mexican film star Dolores del Rio, American film star Paulette Goddard, and French painter Jacqueline Lamba. Among her male conquests was Leon Trotsky, with whom she had a fling while he and his wife were taking refuge with Kahlo and Rivera in the Blue House. She was, in short, something of a “star-fucker,” and there are no reports of Kahlo slumming in the fleshpots of Mexico City.

Kahlo’s bisexuality is recorded in both her paintings and her private life. To start with the latter: the evidence is quite strong that when she visited Paris she had an affair with the great Josephine Baker, the African-American dancer and burlesque entertainer who took Paris by storm in the 1930s. She is also reported to have had affairs with American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, Mexican film star Dolores del Rio, American film star Paulette Goddard, and French painter Jacqueline Lamba. Among her male conquests was Leon Trotsky, with whom she had a fling while he and his wife were taking refuge with Kahlo and Rivera in the Blue House. She was, in short, something of a “star-fucker,” and there are no reports of Kahlo slumming in the fleshpots of Mexico City.

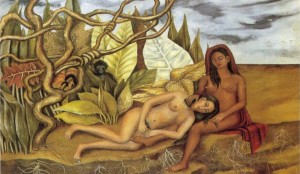

As for her work, the most explicitly homoerotic is Two Nudes in a Forest (1939), which shows two women at the edge of a forest (otherwise barren), one with her head on the other’s lap. The dualism of dark and light, Native and European, is reflected in the two women’s skin tones. The ever-warring forces of health and decay are represented by the starkly divided landscape: to the left a teeming jungle, to the right a barren desert, with no transition in between.

For more information on Out Adventures, visit their website.