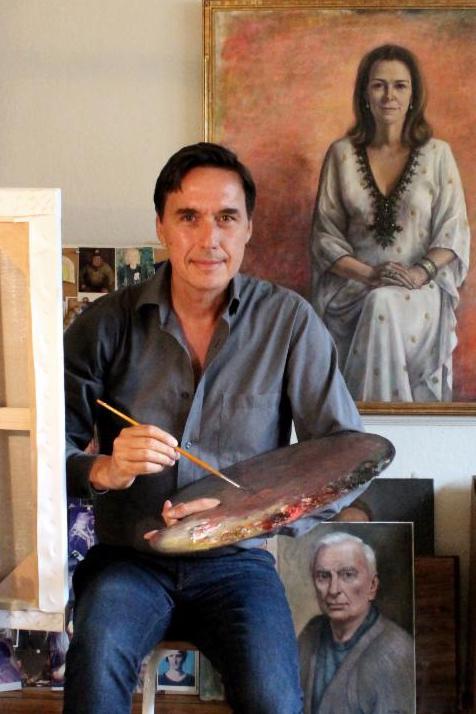

JUAN BASTOS is a portrait painter whose career will soon be on view at a major retrospective of his work at the Denenberg Fine Arts Gallery in West Hollywood, CA, starting on November 5th and running through the 18th. Included in the exhibition will be the covers of several issues of The Gay & Lesbian Review that featured Juan’s art.

JUAN BASTOS is a portrait painter whose career will soon be on view at a major retrospective of his work at the Denenberg Fine Arts Gallery in West Hollywood, CA, starting on November 5th and running through the 18th. Included in the exhibition will be the covers of several issues of The Gay & Lesbian Review that featured Juan’s art.

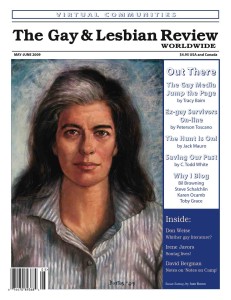

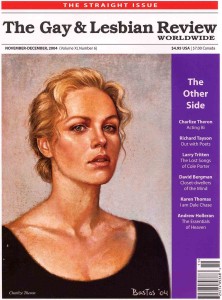

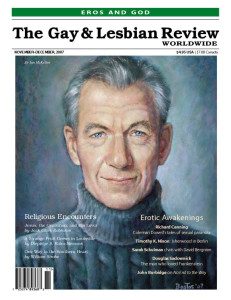

I had a lively conversation with Juan about his career as a portrait artist and about his upcoming show, which is part of the massive Getty Museum project, Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, which is all about Latin American art in Southern California. Juan’s covers for The G&LR, of which there were a dozen in the early 2000s, included portraits of Susan Sontag, Charlize Theron, Ian McKellen, and Gore Vidal, with whom he developed a friendship late in the great writer’s life.

— Chris Freeman

Chris Freeman: Tell me a bit about your background, especially regarding how you first became interested in art.

Juan Bastos: I was born of a Bolivian family in Venezuela. We moved back to Bolivia when I was eleven, and I was happily surprised that two of my relatives were painters, one a portrait painter. Every weekend, we went to their house and I’d sneak into her studio and look at all her work. My mother’s cousin was an artist who lived in Paris. She was a bohemian.

CF: So the life of the artist immediately appealed to you.

JB: In the arts, there is no such thing as age. I was embracing art early. I took private tutoring at fourteen. I briefly studied architecture in Bolivia, and but then came to the U.S. to study commercial art and illustration. However, I very quickly changed to fine arts, eventually graduating from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. I went on to do an MFA at Towson University, nearby. After that, I was able to make a living as an artist. I had commissions for portraits then and was also exhibiting, including figurative work and magical realism. But I stopped doing that kind of work in 1995.

CF: How did you get started as a portrait artist, and how did you learn the craft?

JB: At first, I did a lot of pencil drawing. I stopped painting at sixteen and just drew. Drawing is the basis of everything. I had very good control through drawing; so for composition, everything was there, but I had to learn to use color. I’m a bit of a purist. I explored mixed media, but I wanted to really know how to draw and how to paint.

CF: So the technical part is very important.

JB: Extremely important. You copy great masters. You learn their technique. I was copying Leonardo da Vinci when I was a teenager. You learn shading, how to draw hair; you learn certain brush strokes. One of my relatives, a painter, put a few brushstrokes on my canvas once when I was young, and I still have a little bit of that from her. When I paint, there is a little bit of the expressive quality that she had. My inspiration was the great masters, but blended with my own South American style. There is some Latin American flair in my work.

CF: As a Latin American artist, it must be a great honor for you to be part of this huge Getty Museum project “LA/LA.” Your show is opening in West Hollywood in early November at a local gallery.

JB: What’s interesting is that a lot of art coming from Latin America has a political presence; mine in this exhibit doesn’t really. These are portraits; some were institutional commissions, family portraits. It will be interesting to see my work in that context. I have never seen an exhibition of commissioned contemporary portraits, really ever. So I’m delighted that the Denenberg Gallery is hosting this show for me. I will have a few landscapes and a self portrait. It is interesting to share my exhibition with other artists whose vision is very different from mine. Years ago, I used to exhibit my work that was more in the magical realism style in Peru, in Washington, DC, and I was part of a biennial in Egypt, representing Bolivia. I had a group show in Paris. But I stopped working in that style over twenty years ago to be completely dedicated to portraiture.

CF: You have a friendship and with the great L.A. artist Don Bachardy. Tell me how you met him and what your relationship has been with him over the years.

JB: I had his book October, which featured his drawings and his lover Christopher Isherwood’s diaries. I had some of the post

cards of Don’s work. And then I went to a show of his work in the late 1990s in Laguna Art Museum. I loved the work. I asked a person who worked at the museum if there was a way Icould get his address; somebody who happened to be walking by and overheard told me that address, from memory! So I sent him a letter, saying that I’m a portrait artist and that I’d love to meet him. His reply came on a postcard of his portrait of Gore Vidal. I invited him to come for dinner and then he asked me to sit for him. Afterwards, I said, “Don, now you have to pose for me.” He said, “tit for tat!” I hadn’t heard that expression before, but it sounded like what I meant.

CF: Your portrait of Don is remarkable and it’s rather inspired.

JB: In the studio, there were all these portraits of Chris by Don, so I knew I wanted to use that in my portrait of Don. I remembered the David Hockney portrait of them together. In my portrait, both men are about the same age; Don is the age that Chris is in the background portrait. Don said, “Juan, you captured Chris’s eyes.” I said, “Well, I copied your portrait,” but he insisted: “No, Juan, you interpreted it.”

CF: That’s an artist speaking to an artist.

JB: He was so pleased that he gave me a portrait of myself that he had done, and he has my portrait of him, which I’m borrowing for this new show.

CF: How do you place yourself in the context of Bachardy? You are both obsessed with portraiture.

JB: He’s even more obsessed than I am, because of how he works. We both work from life, but he works only from life. Everybody I work with poses for me, at least once or twice, and I help myself with photographs. The live pose is amazing. When people pose for me, I engage them in conversation; Don doesn’t really do that. But he has so little time; he does two or three finished portraits in one sitting, whereas my work takes much longer. I enjoy talking to people; I approach them that way, so I can catch something special. One client asked if she could talk on her cell phone while I worked; I said sure. She was like a young girl talking to her friends, so I tried to capture that in her portrait.

CF: Don talks about his work as a confrontation. But that’s not your style.

JB: No, every portrait is a challenge. I have to create the illusion of life on a two dimensional surface. That’s where I get the kick, trying to capture something in the portrait. As a student, I loved doing that, and as the technique gets better, so does the ability to capture that kind of life. That’s why I’ve kept obsessing. I’ve had sitters who are very guarded. I have to find a way to get them to open up. And because I tend to have a good deal of time with each sitter and I talk with them, I become something of a bartender. They take me into their confidence, so then I have to be a little discreet. It’s almost like therapy for some people. I end up with many stories.

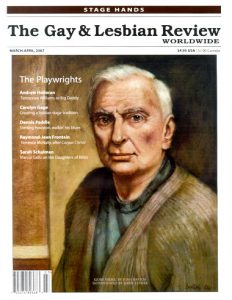

CF: Well, that brings us to Gore Vidal, one of the great raconteurs. You painted him for the cover of The Gay & Lesbian Review, correct?

JB: I was supposed to meet him just to take photos to use and then leave; I stayed for two hours. This was at his house in L.A. I had never met him before or  even read him, but I did read some of his work and took the books for him to sign. After I took the pictures, I said, “Gore, I need you to pose. I want you to be happy with the portrait when I finish it, and the only way that’s possible is if you pose for me for one sitting. Then, you can approve it and I’ll send it to The GLR.” We didn’t talk much, but I said, “Gore, this has been a great experience for me. May I come back to visit you?” He said, “Mi casa es su casa.” So, for the next two years, I visited him every couple of months. He really screened his visitors, so it was very special to spend that time with him. I wrote down our conversations.

even read him, but I did read some of his work and took the books for him to sign. After I took the pictures, I said, “Gore, I need you to pose. I want you to be happy with the portrait when I finish it, and the only way that’s possible is if you pose for me for one sitting. Then, you can approve it and I’ll send it to The GLR.” We didn’t talk much, but I said, “Gore, this has been a great experience for me. May I come back to visit you?” He said, “Mi casa es su casa.” So, for the next two years, I visited him every couple of months. He really screened his visitors, so it was very special to spend that time with him. I wrote down our conversations.

CF: Can you share one of those gems with us?

JB: Of course! He had a picture of Isherwood next to his bed. I remarked that it was a nice picture, and he said, “Yes, we were good friends.” He also had a picture of Howard Austin on the wall. I asked about it. He said, “Don Bachardy did that one.” Gore liked it a lot. He was closer to Chris than to Don. I asked him about Chris, and he said, “pas mal.” Not bad. I said, “I understand his English was beautiful but his German not so much; it sounded more working-class because, Don told me, he had learned it from hustlers in Berlin.” Gore replied, “The things one can pick up for ten dollars!”

CF: And Gore liked your portrait?

JB: He did. He even compared my work to John Singer Sargent more than once. When I was putting together my website I said, “Gore, can I ask you a favor? I want to use that Sargent quote from you for my website. May I have it?” He said, “Well, I’m not happy about it. However, I’m not unhappy about it either.” So, I said, “I completely understand. I will not use it.” He said, “Juan! I’m telling you I’m not unhappy about it.” I reached over and touched his knee and told him that I wouldn’t use it unless he was happy about it. After a pause, he said, “All right! All right!” Later, when I did the portrait of Rudolph Nureyev for The GLR, I took the original for Gore to see. He liked it very much and he said that he thought Nureyev would have liked it. I also did a portrait of a young Lincoln with Joshua Speed in the background. Gore loved that one.

CF: How did you come to work with The Gay & Lesbian Review, which is published in Boston?

JB: My husband, Tom Parry, went to Harvard and was president of the Harvard Gay & Lesbian Caucus, an alumni/a organization. So he introduced me to  Richard Schneider through those channels. As you recall, the original name was The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review.

Richard Schneider through those channels. As you recall, the original name was The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review.  Richard told me he needed some illustrations and other artwork, so we started to work together. I did Tennessee Williams, Susan Sontag, Sir Ian McKellen. When the latter saw the portrait he said, “I love it, but where are the wrinkles?” I also did Charlize Theron for GLR; I didn’t get to meet her. She was in Europe making a film. So I chose a photograph but changed the direction of her eyes in the portrait. When you paint someone very beautiful, there is the danger that it could look like a cover for a fashion magazine, so I wanted to give her more depth. She’s extremely talented, so I wanted to be sure to capture the weight of that talent in the portrait. Someone told me that when she got an award at GLAAD, my portrait was shown during the presentation.

Richard told me he needed some illustrations and other artwork, so we started to work together. I did Tennessee Williams, Susan Sontag, Sir Ian McKellen. When the latter saw the portrait he said, “I love it, but where are the wrinkles?” I also did Charlize Theron for GLR; I didn’t get to meet her. She was in Europe making a film. So I chose a photograph but changed the direction of her eyes in the portrait. When you paint someone very beautiful, there is the danger that it could look like a cover for a fashion magazine, so I wanted to give her more depth. She’s extremely talented, so I wanted to be sure to capture the weight of that talent in the portrait. Someone told me that when she got an award at GLAAD, my portrait was shown during the presentation.

CF: Do you think of yourself as a gay artist?

JB: Well, I’m an artist, and I’m gay. When you are doing a portrait, you sort of put yourself in the position of an actor. You have to make a connection. In all of my portraits, there is something about me. So if a woman poses for me, there has to be a common denominator in my essence, my spirit. I grew up surrounded by strong women: my sisters, my mother, my grandmothers. So when I do a portrait of a woman, I like to reinforce their strength. When I was a student drawing human figures, our teacher told us to first assume the pose. If the model’s arm is up in the air, we would put our arms up. We could feel the pressure, the stress of the pose, and that was necessary in order to paint the picture. When you do a portrait, you put yourself in their situation.

JB: Well, I’m an artist, and I’m gay. When you are doing a portrait, you sort of put yourself in the position of an actor. You have to make a connection. In all of my portraits, there is something about me. So if a woman poses for me, there has to be a common denominator in my essence, my spirit. I grew up surrounded by strong women: my sisters, my mother, my grandmothers. So when I do a portrait of a woman, I like to reinforce their strength. When I was a student drawing human figures, our teacher told us to first assume the pose. If the model’s arm is up in the air, we would put our arms up. We could feel the pressure, the stress of the pose, and that was necessary in order to paint the picture. When you do a portrait, you put yourself in their situation.

CF: So it’s a kind of empathy or identification that you’re striving for.

JB: When people see this new show, they’ll see the portrait I did twenty years ago with Tom. It is an intimate portrait; it’s clear that it is two men, together. Back then, early in our relationship, I was still somewhat in the closet, especially back in Bolivia. So it was important for me to do that painting at that time. It was an affirmation. It was a symbol of our relationship, and we actually used it for our Christmas card. The portrait is self-explanatory.

CF: As an artist, you can’t hide. You have to reveal yourself.

JB: I took Tom to Bolivia; we went to my high school reunion. Everything was fine. But we were the poster boys at the time. It was a new thing in a traditional culture. Recently, I was interviewed for a Bolivian newspaper, and they asked if I was married. I said, “Yes, and his name is Tom.” They loved that. It is important for young people to have role models; the fact that I’m out, I hope, helps young artists. Knowing that Michelangelo was gay gave me inspiration when I was young. I’m glad to be out.