“Keep everyone afraid and they’ll consume.”

— Marilyn Manson

UNTIL LATE in the 20th century, gay men were almost as invisible in the media as lesbians. We began to be discovered by corporate America some time in the mid-1970’s, and by the 1990’s we were being treated as an important target market. The initial commercialization of gay life was followed within a few years by the AIDS crisis, and the two have been interacting ever since. AIDS-related ads began to dominate the gay media by the late 1980’s and have been recapitulating, augmenting, and shaping gay mythology and iconography ever since. Their powerful influence has affected our desires, our self-images, and our fears. Once marginalized, our lives, our behavior, even our deaths, have become valuable commodities.

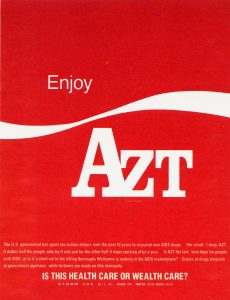

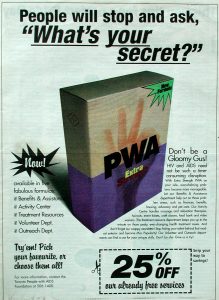

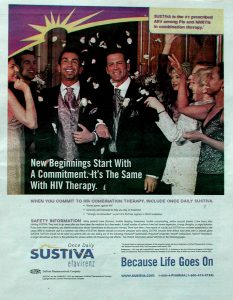

More than two decades after the first cases of AIDS were identified, what began as a puzzling syndrome without a name has grown into a world-wide, multibillion dollar industry. Drug manufacturers, researchers, physicians, clinicians, social workers, lab assistants, grief counselors, hospice managers, safe-sex educators, insurance agents, accessories manufacturers, pharmacists, publishers, social service administrators, record clerks, and red ribbon snippers all have a stake in the future of AIDS. In Scotland, it was ascertained that the country has seven AIDS workers for every person with AIDS! More money per patient is spent on AIDS than on any other disease in history. A large proportion of this outlay involves AIDS education, “safer sex” messages, and other AIDS-related advertising. Companies selling AIDS-related wares are the largest advertisers in the gay media today (replacing the manufacturers of nitrite inhalants, whose ads dominated the gay media in the 1970’s and early 80’s). Pharmaceuticals, clinics, insurance buyouts, home testing kits, fundraising walkathons, and kitschy AIDS jewelry are all advertised widely in mass-market magazines for gay men.

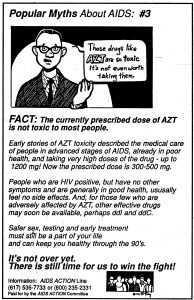

In North America, such advertising has been aimed for the most part at gay men, who (along with their physicians) have remained the chief target group for AIDS-related products and services. As the paradigm of AIDS has enveloped the gay community, the foundations of the AIDS industry’s proliferating superstructure have been under considerable stress. The hypothesis of a single, fatal retrovirus, HIV, as the sole cause of an ever-lengthening list of diseases, conditions, and test results has produced wildly inaccurate epidemiological predictions, no vaccine, no cure, and still no safe treatment. The official definition has been altered more than once. People diagnosed with AIDS in 1984 were in very bad shape indeed; today, even an ostensibly healthy person can be said to have AIDS on the basis of blood readings alone. Gay men, considered a “high risk group,” are under great pressure to take these tests, and told they will die of AIDS unless they take very expensive, toxic drugs, rigorously, for the rest of their lives. Still, most Positives take no prescribed AIDS drugs at all, and people (with or without drugs) are living far longer with their death sentences now than they used to. AIDS has changed from a medical syndrome to an ideology supporting a lifestyle reinforcing an industry.

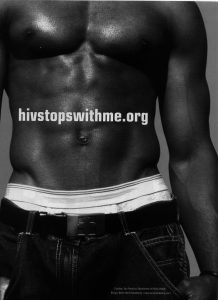

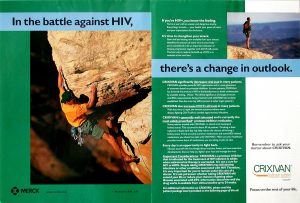

Even The Advocate, ordinarily no critic of the AIDS industry, has commented on the aggressive promotion of the HIV-positive lifestyle: “Everywhere you look, the media send the message: ‘It’s sexy to be HIV-positive.’” For many gay men, being “poz” has become an important aspect of their identity. Glossy magazines heavily subsidized by the pharmaceutical industry promote the poz lifestyle. In colorful ads, teams of handsome, shirtless HIV-positive hunks, pull together to cross the Pacific Ocean in small boats painted with the names of their dead friends; rugged mountain men scale dangerous peaks thanks to the latest AIDS drug. (The Benneton company has taken a different approach: their photograph of a man grieving over his emaciated son in a version of the Pietà was meant to sell sweaters.)

The development of the new AIDS lifestyle from the gay clone lifestyle of the 1970’s was described by the late Paul Reed in his 1994 book The Savage Garden. Many of his friends, he wrote, “have resumed a life that is in many ways similar to the life we pursued a decade ago—the gym, the afternoon rest … the clubs. … The difference is that we now no longer work to pay the bills, we simply collect our disability checks. And we no longer feel that this is the beginning of a hot, fast, life. It may be the last party, the final fling.”

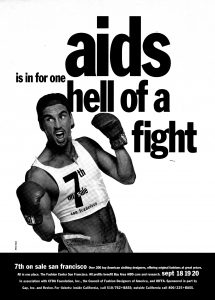

AIDS-related print ads aimed at gay men often conflate a number of recurring motifs and themes, amont them: sexual potency and death; masculinity and consumption or glamour; fear and risk. Accompanying this brief introduction is a selection of display ads aimed at gay men that appeared in North American magazines and newspapers over the years. My comments on these items are offered as suggestions, possible interpretations, exploratory probes into the language, imagery, and folklore of the AIDS culture.

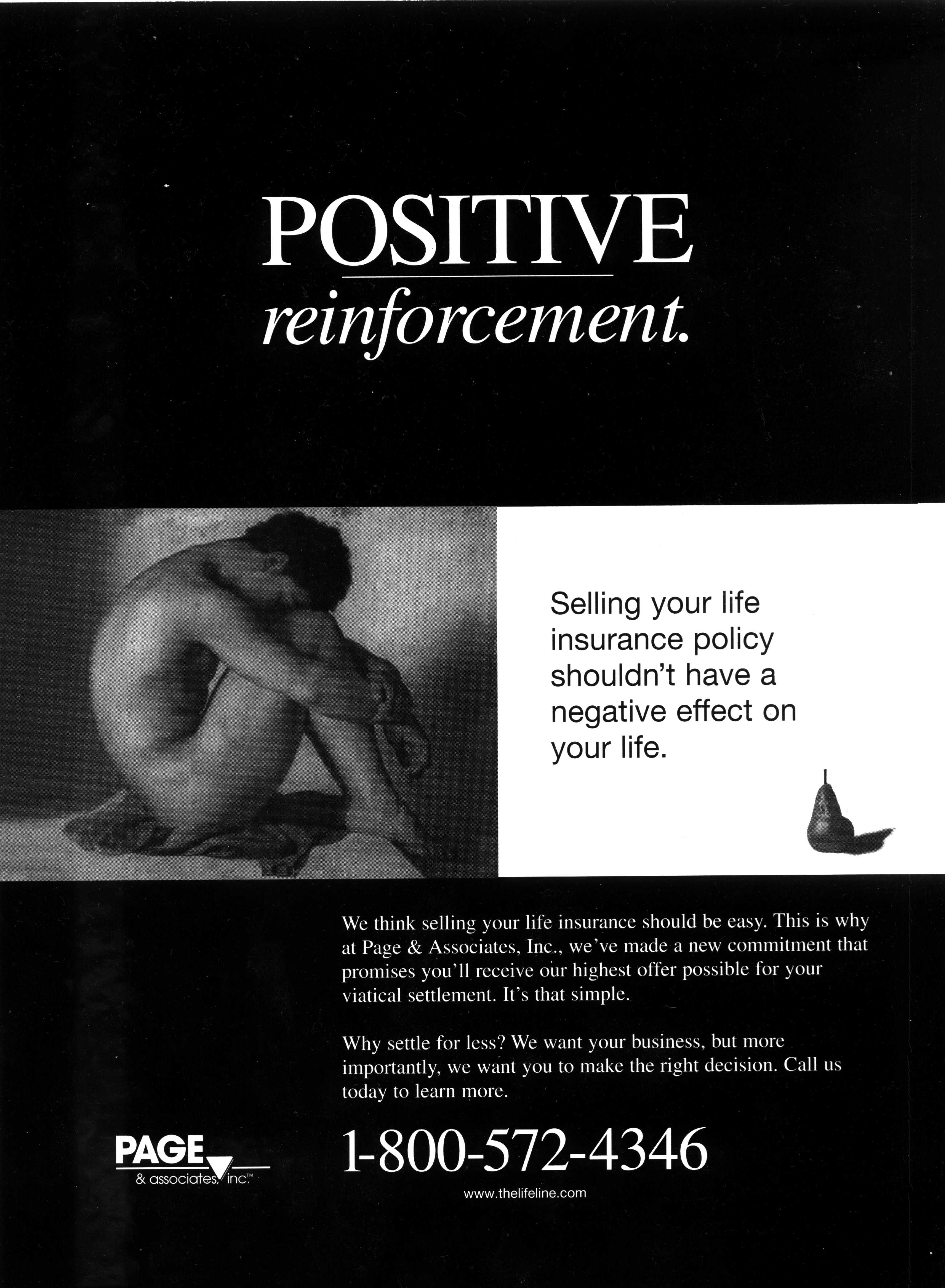

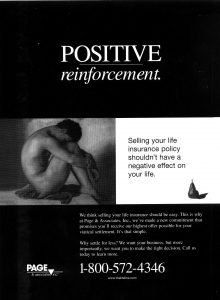

The viatical ad depicted here employs a 19th-century painting by Flandrin popular with gay men since Baron von Gloeden created a black-and-white photographic version early in the 20th century. The work is frequently reproduced in the gay media, appearing on book and playbill covers and in ads for everything from dances to clinics. Why has it exercised such a persistent fascination for gay men? Describing the pose (without reference to the painting) in his 1977 book Manwatching, anthropologist Desmond Morris writes: “This is perhaps the most impressive way of creating a second person out of one’s own body.” In other words, a clone. “The doubled-up legs,” he explains, “provide a shape that can be embraced, leant against, and rested on. The arms, trunk and head all feel the comfort of body contact.” The posture, he maintains, has been found to be nineteen times more popular with women than with (heterosexual) men! “Perhaps the reason is that the posture is so extensively self-comforting that it begins to reveal its infantile connections too clearly, and males shy away from it.”

The knees-up boy makes frequent appearances in viatical ads urging the HIV positive to sell their policies in return for “relief fast” and “a cure”—for financial stress. Like the AIDS Quilt and the teddy bear, the knees-up pose reinforces themes of “comforting” and infantalizing prevalent in AIDS discourse. The ad’s offer of “positive reinforcement” and denunciation of “negative effects” reflects and reinforces the “positive = good” assumption embedded in the language.

It remains to be seen how long the cultural infrastructure of the AIDS industry and its influence over the gay community will last; it may well depend on the new generation of gay men. A young man of 21 now entering the gay world was born in 1981, the year in which the syndrome now known as “full-blown AIDS” was first identified. His life has been spent in a society that holds a certain set of beliefs and assumptions about gay men, gay sex, disease, and death. His attitude toward those beliefs and assumptions will determine how he responds to the very mixed messages that the media place before him. If he is to become as much a part of the AIDS culture as previous generations, he must first be induced to buy not only the publication, but the diagnosis, as well.

Ian Young, a writer based in Toronto, is the author of The Stonewall Experiment: A Gay Psychohistory and a two-volume bibliography, The AIDS Dissidents.