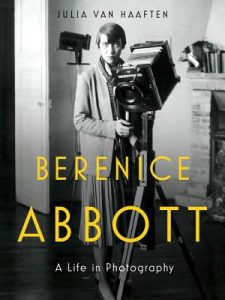

Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography

Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography

by Julia Van Haaften

W. W. Horton. 634 pages, $45.

BERENICE ABBOTT was a larger-than-life photographer who captured the architecture of New York City, as well as some of its noteworthy inhabitants, from the 1930s to the 1960s and beyond. Julia Van Haaften, founding curator of the New York Public Library’s photography collection, has written a monumental biography of Abbott’s life, an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach that’s brimming with facts and anecdotes about her subject’s life.

Abbott (1898–1991) grew up in a working-class family in the Midwest. She fled her home as soon as possible and set off on a journey of self-discovery and self-creation as an artist. Van Haaften traces in detail Abbott’s evolution as a photographer. We learn that her initial interest was sculpture and that this later morphed into curiosity about making photographs.

While out of work and starving in Paris, she fortuitously met the well-known photographer Man Ray, who hired her as a darkroom assistant. It wasn’t long before she left his studio and set up her own rival studio specializing in portraiture. There she photographed André Gide, Djuna Barnes, James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, and Sylvia Beach—a who’s who of bohemian cosmopolitans. She photographed lesbian journalist Janet Flanner in what has become a signature example of lesbian photographic portraiture. Flanner is dressed in a jacket, striped pants, and a top hat adorned with costume masks, and has an expression of Je ne sais quoi. Flanner (writing under the pseudonym Genêt) promoted Abbott’s work in her column “Letter from Paris” in The New Yorker.

While in Paris in the ’20s, she discovered the photography of Eugene Atget (1857–1927) and became a devotee of his work. Atget, the quintessential flâneur, roamed the streets of Paris photographing street scenes and buildings in an attempt to document life before modernization’s final blows. Abbott embraced Atget’s project and saw him as “a Balzac of the camera.” After he died in 1927, Abbott purchased much of his archive—over 1,500 glass negatives and 8,000 prints. Eventually, after many perilous twists and turns, Abbott sold the Atget Archive to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

Abbott left Paris in 1929 and set up a studio on Commerce Street in New York City. Her subjects were architecture and documentary work, primarily of the city itself. Her black-and-white photographs from the 1930s are her major claim to fame. Nightview was taken from atop the Empire State Building in 1932 and caught a spectacular view of a glittering, electrifying city. Abbott advocated an “egoless photography” in which the subjectivity of the photographer remained “out of the picture.”

While in her thirties, Abbott was introduced to art critic and historian Elizabeth McCausland. The two women became partners in life. They set up residence in Greenwich Village at 30 Commerce Street, where they lived in two adjoining apartments that also served as work spaces. McCausland was a member of the Communist Party, though Abbott, a “fellow traveler” philosophically, did not join. That did not prevent the FBI from opening a file on Abbott in 1951, ostensibly because of her association with McCausland. The file mentions her “homosexual associations” and the fact that she “wears slacks constantly.” In short, they were targeted for being lesbians.

For the most part, Abbott lived a semi-closeted life. People who were “in the life” themselves knew about her lesbian affairs. She was a drinker, smoked like a chimney, and loved to dance. She had many lesbian affairs beginning with Thelma Wood (the lover of Djuna Barnes). It was in her professional life that she attempted to keep in the closet. Like many lesbians of her generation, she wanted to be seen as an “artist”—with no modifier placed before the word. Van Haaften notes that Abbott was supportive of feminism but indifferent to the emerging lesbian and gay rights movements. In 1965, McCausland, her partner and collaborator of thirty years, passed away, but Abbott was not mentioned in the obituary—standard practice in pre-Stonewall America. Soon thereafter, Abbott moved to Monson, Maine, where she resided until her death in 1991.

The last half of this mammoth biography includes more about Abbott’s honors and visits from young acolytes than most readers will want or need. Van Haaften has amassed an enormous amount of research, references, and an excellent index, though I for one would have liked more analysis and less piling up of facts. An examination of Abbott’s photographs raises so many questions concerning her ideas about objectivity in photography—this desire to adopt an “egoless” stance. Is such an æsthetic possible or even desirable? Could this theory be an outgrowth of Abbott’s life in the closet, where subjectivity had to be hidden from view?

Berenice Abbott remains a major influence in photography today. Her work is visually breathtaking—immediate, clear, and indelible. Van Haaften has written a book that’s a major resource for fans of urban and architectural photography.

Irene Javors is a psychotherapist in private practice who’s based in New York City.