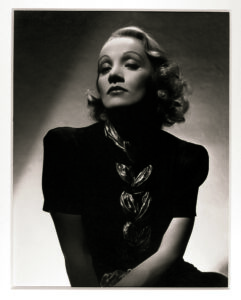

Play The Part: Marlene Dietrich

International Center of Photography

September 29, 2023- January 8 2024

Location: 79 Essex Street, NYC

Play The Part: Marlene Dietrich, on view at the International Center of Photography (ICP), is an exhibit that focuses on Dietrich’s evolving public persona as reflected in 250 photographs spanning the years 1905-1978. The collector, Pierre Passebon, has provided the photographs for the show. Passebon’s collections offers viewers a window into Dietrich’s construction and presentation of her public self. His collection includes photographs by George Hurrell, Eugene Robert Richee, William Walling as well as Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, Lee Miller, and Eve Arnold. Passebon’s book Obsession: Marlene Dietrich: The Pierre Passebon Collection (2017) is available for purchase at the ICP.

The exhibit occupies an entire floor of the ICP. Beginning with photographs of Marlene’s childhood in Berlin in 1905, we are offered decade-by-decade documenting of her development as a public figure from her early Weimar days to the final photograph of her as an elderly woman. The images reveal the multiple parts Marlene presented to the world as she carefully molded her presentation of self. She used camera angles, lighting, shadows, fashion, and sexual and gender ambiguity to beguile and mystify her audiences. We see Marlene in the 1930 film Morocco, in top hat and tails, kissing a woman on the lips while simultaneously flirting with a man. In The Blue Angel (1930) she is the temptress who destroys her besotted lover.

As an actor in the Hollywood dream factory, she played roles that teased, dared, and flirted with audiences. She bucked the Hollywood studio system as well as subverted the censorious Hays Code with her gender-bending, trouser-defying behavior.

The photographs also explore her work with the USO during World War II. She toured throughout Europe, entertaining troops and helping refugees escape the Nazi war machine. She despised Hitler and the Nazis and renounced her German citizenship, so she became an American citizen. In 1947, She was the first woman to be given the Medal of Freedom.

As she aged, she developed her cabaret act wherein she toured Las Vegas and major European music halls. We see photos of her performing at various venues. She played the part of the chanteuse brilliantly and attracted standing room only crowds.

This exhibit focuses on Dietrich’s love of the photograph as the penultimate vehicle for achieving control over the construction and representation of the performing self. She distinguished between the public self (the self that she displayed in real time) and the performative self, or the perfected self that could be confected into a legend, or a myth. The photograph was the perfect vehicle for this dual expression because she could edit and technically master the image to achieve a desired perspective of herself.

Such intentional imagery has the power to conquer aging and death. Her photographs became a medium to achieve immortality. Marlene found a way to become mythic and at one with the gods and goddesses of glamour and myth.

The film critic Andrew Sarris called Dietrich the “Empress of Desire.” He saw her performative self as the embodiment of all that we desire but may or may not allow ourselves to act out in our lives. She was desired by both men and women. She played roles that were filled with contradictory if not paradoxical needs and wants: mother/prostitute; gender/sexually fluid flirt; world weary yet romantic lover.

The first time I saw Dietrich in a movie was at a seedy art house venue in Manhattan. I was in college, on one of those endless breaks between classes. The film was Morocco. At first, I thought the movie really old-fashioned, but then Dietrich entered the frame. She was dressed in a top hat and tails and sported a flower. She sang and started walking over to the seated crowd. The next thing I knew she went over to woman and without warning planted a kiss on her lips. I was transfixed by the scene; I had never seen a woman kiss another woman like that on the screen.

I found myself titillated, filled with desire and embarrassed for having such feelings. This was the 1970s, and I was not supposed to have such feelings. Yet, here was Dietrich, acting out her desire on the silver screen in 1930. She had defied convention and she managed not only to get away with it, but became a star because of it.

Her defiance of convention or more positively her validation of desire through her use of film as well as the photograph allowed viewers to vicariously experience their own repressed needs and desires. As a matter of fact, she gave desire a patina of glamor and blessing.

Playing The Part: Marlene Dietrich is an exhibition that asks us to think about how images made in the films and photographs of Marlene Dietrich functioned to ultimately ‘play the part’ in the construction of the legend of Marlene Dietrich. She would not allow anyone to photograph her in her old age. Maximillian Schell attempted to do so in his documentary Marlene (1984) but she would not let him film her. She wanted to be remembered as the perfected performative self as depicted in her photographs and films and not as the aging mortal. She maintained control of her image until the end of her life. In so doing, she managed to overcome the vicissitudes of time and remain an immortal legend. For me, she was not only, as Sarris calls her “Empress of Desire,” but also “Empress of Queerness,” she who challenged the norms of desire.