René Blum and the Ballets Russes:

René Blum and the Ballets Russes:

In Search of a Lost Life

by Judith Chazin-Bennahum

Oxford University Press

277 pages, $29.95

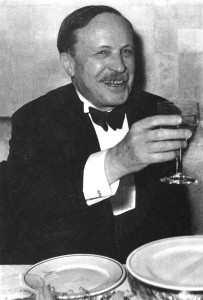

BIOGRAPHER Judith Chazin-Bennahum, former ballet dancer and distinguished professor emerita of theatre and dance at the University of New Mexico, has taken on the task of recovering from obscurity the extraordinary life of René Blum (1878–1942). Youngest brother of Leon Blum, the first Jewish prime minister of France (1936–37), René devoted his life to the arts and ballet, and to the Ballets Russes above all.

René Blum was the editor of the very chic early 20th-century literary journal Gil Blas. While in this position he met and worked with Claude Debussy, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, André Gide, and Paul Valéry. He served in World War I, received the Croix de Guerre for bravery, and became a national hero for his efforts to save the artworks in Amiens Cathedral from destruction. Blum was arguably the first to recognize the genius of Proust’s Swann’s Way, and he helped to arrange with Bernard Grasset for the book’s publication. He belonged to the same circles as Proust and knew the outrageous and provocative Robert de Montesquieu, on whom Proust based the homosexual character Baron Charlus, and sent him affectionate letters during the war.

René Blum does not provide extensive material on Blum’s sexuality. We do learn that the love of his life was Josette France, with whom he had a son, Claude-René. Early in Blum’s career, a close friend, the playwright Georges de Porto-Riche, warned him against getting too close to Proust due to rumors about the latter’s homosexuality. But Blum disregarded such advice and maintained close connections with Proust and other members of France’s art world regardless of sexual orientation. Actually, it was his status as a Jew that placed him in a very precarious position within French society. He lived in the shadow of the Dreyfus Affair, and his pro-Dreyfus sentiments did not endear him to the anti-Semites in France’s cultural elite. Blum would ultimately meet his death in Auschwitz.

His greatest legacy was his work as a ballet impresario. In 1924, he was appointed artistic director of the Théatre de Monte Carlo—Serge Diaghilev’s home base for the Ballets Russes. Following Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Blum went to work and by 1932 established a new Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo. His triumphs there were punctuated by internecine battles with his partner Col. W. de Basil, the Russian Cossack turned ballet director. During the 1930’s, Blum managed to get the best of Diaghilev’s dancers, choreographers, and ballet masters to perform with the newly constituted Ballets Russes. The great talents of Fokine, Balanchine, Massine, and Nijinska were brought to bear on the phenomenal productions of the company. By the late 1930’s, Blum was able to bring the Ballets Russes on tour to America; in doing so, he helped to create audiences for dance where there were none before.

In 1940, while still in America, Blum witnessed the fall of France to the Nazis. He insisted on returning to Paris to be with his family. As a recipient of the Croix de Guerre, he regarded himself as a French citizen and a war hero, and he believed that he would not be harmed. He did not foresee that, as the brother of the prime minister of France, Léon Blum, a Jew and a Socialist, the Nazis would see him as a prime target for arrest. René Blum was picked up by the Nazis on December 12, 1941. Along with 700 “notable” French Jews, he was imprisoned in a camp at Compiègne. Though in poor health and starving, he summoned the energy to give lectures on literature and dance to other prisoners while they awaited deportation. In short order, he was transported to Drancy, and then, on September 23, 1942, to Auschwitz, where he was sent to the crematorium and burned alive.

This biography is a must–read for all balletomanes, especially those who are interested in the history of the Ballets Russes and its impact on the development of modern dance. There are excellent descriptions of the demands of running a dance troupe as well as interesting anecdotes about dancers and choreographers. This reader would have liked a lot more discussion about Blum’s personal life, his Jewish heritage, and his involvement with the Dreyfus Affair, not to mention his relationship with Proust. The large amount of raw material needed to be synthesized more fully, while the biographical aspects of Blum’s life could have been better contextualized within the historical period in which he lived. This could have provided a better platform for understanding the importance of Blum’s cultural contributions. Still, Chazin-Bennahum has brought René Blum and his work back into view, recovering the narrative of an exceptional life tragically cut short by the Nazis’ barbarism.

Irene Javors, who teaches mental health counseling at Yeshiva University, is the author of Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living (2010).