Author’s Note: This portrait is drawn primarily from the Barbara Deming Papers at the Schlesinger Library (BDSL) and is a rewritten, much condensed version of the one that appears in my 2011 book, A Saving Remnant (New Press). Unless otherwise specified, all quotations come from BDSL.

BORN IN 1917 into an upper-middle class Manhattan family that was largely traditional in their habits and opinions, Barbara Deming—destined to become a leading lesbian-feminist writer and activist of the postwar era—felt closer to her “caring and principled” father than to her self-absorbed mother. Among her father’s concerns as his daughter approached adulthood was that she should focus her attention on finding “a good man to marry.” Though Barbara at age sixteen was still a dutiful daughter, she surprised herself by falling in love instead with Norma Millay, a neighbor at the family’s New City country home and the sister of Edna St. Vincent Millay. The passionate affair was broken off only when Barbara left for Bennington College in 1934.

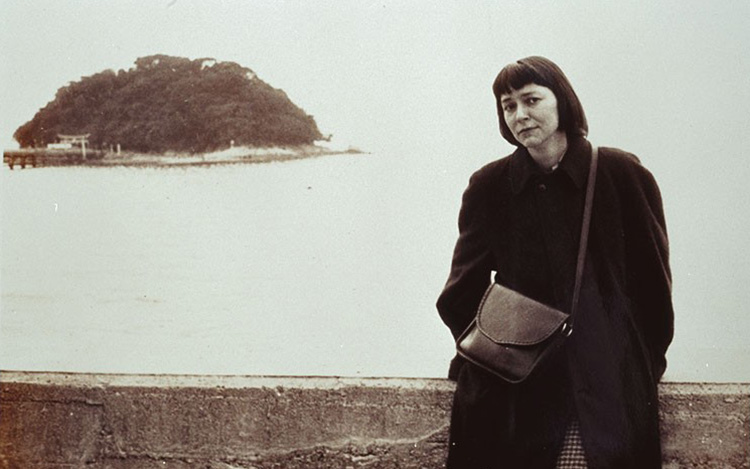

At Bennington she studied English literature, grew into a strikingly attractive woman, tall and willowy, with straight black hair and bangs. She eschewed makeup and dressed simply, slept with men and women and had one serious if intermittent affair with an older student, Dorothy (“Casey”) Case. It was not a matter of rebelling against her father’s wishes or setting out to displease him; she simply was drawn to women far more than to men.

On graduating from Bennington, she worked for several years as low-level staff in the theater, picked up a master’s degree in drama, and again fell in love with a woman—who ended up leaving her to marry her brother. Initially stunned, Barbara accepted the shift in sentiments and remained friendly with the new couple. As she wrote in A Humming Under My Feet (1985): “if love is really love, it cannot stop being what it is—though it can stop seeking. … Then it changes, certainly; but it does not expire. Even when one falls in love again.”

Emotionally and professionally unsettled for roughly the next decade, Barbara had enough income from a bequest to travel quite widely. In Turin she had a brief affair with “Pete,” a man she’d met earlier in the States, but when he announced during intercourse “I’m fucking you,” Barbara’s “whole self,” as she later put it, flinched “as if slapped by his words.” No, she recognized with a jolt, “he never will know me and I never will know him. For this penis” has been taught to think itself “Lord and Master. And I am not the one to unteach it this inanity. … My spirit stands still—absolutely attentive at last. … I am this self that I am. I affirm it. Yes, I am. And I will not be robbed.”

Her sexuality affirmed, Barbara and Mary Meigs, a gifted painter and writer, fell in love in 1954. Mary came from a wealthy, socially prominent family (one ancestor had been a signer of the Constitution) who lived in D.C., in the five-story redbrick house previously owned by Alice Roosevelt Longworth. Yet the Meigses were something of an anomaly: they shunned ostentation and supported the Democratic Party. Mary herself had been well educated, was outspoken and candid, and shared Barbara’s preference for living rather austerely and close to nature. The two women took a house together in the town of Wellfleet on Cape Cod.

Their nearby neighbors were the novelist Mary McCarthy and her ex-husband, the well-known critic Edmund Wilson, who was very drawn to Mary—even to feeling at one point that he might be falling in love with her. He asked Mary directly if she was a lesbian, and Mary, startled, hedged in answering (“well, yes—sort of”). This was, after all, the 1950s, when it was almost universally assumed that homosexuality was a mental illness. It was a time when, despite the existence of an incipient gay movement, most homosexuals did their best to remain in hiding. As Mary once put it, she and Barbara lived in “the shadowy world of denial and pretense,” though openly living together: “We lead double lives … the most beautiful and loving experiences of our lives have to be kept secret; and the lives we live make us wary and cold.” Edmund Wilson’s attitude didn’t help. Mary recorded his words to the effect that “homosexuality is in contravention of some immutable law … lesbians are faintly ridiculous.”

Barbara’s acceptance of her lesbianism was paralleled by her political evolution. During the Korean War, she had accepted the U.S. assertion that the conflict was inevitable—essential to the “national interest.” By the presidential election of 1952, she’d gotten to the point where she handed out buttons for the Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson. By the end of the ’50s, she and Mary set off on a prolonged series of travels that moved her much further along on the leftwing spectrum. In Israel, Barbara somehow got to spend a whole evening alone with Martin Buber discussing nonviolence; in India she read Gandhi much more deeply than before; and in Cuba she formed the firm conviction that under Castro the island had finally “gained its independence from us”—and that was “as it should be.” She did, though, regret Castro’s resort to violence, and in 1960, back home in the States, she became involved with the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA) as well as, more generally, the issues of racism, civil defense, and nuclear disarmament.

From that point on, her commitment to nonviolence would remain firm, yet at the same time she never rigidly dismissed “for all people at all times and places methods of violent and armed struggle.” After all, it had been central to the success of the American Revolution. Barbara believed that it was “crucial to establish women’s right to violent self-defense when under attack.” Mary admired Barbara’s deepening sense of mission and her bravery in pursuing it, but she abhorred the idea of going to jail or participating in a plethora of meetings and demonstrations. She decided that her true path was her art—that, and “caring about the life around me … being attentive to my own rhythms, to the messages that I received when I kept very still,” as she said in a 1978 interview in Ms. magazine. By the early ’60s, she and Barbara had begun to move steadily in different directions.

Martin Duberman’s recent books includeHas the Gay Movement Failed? and Jews Queers Germans: A Novel.