Editor’s Note: What follows is excerpted from a longer piece that will soon appear in The Line of Dissent, a collection of the author’s essays published in this magazine over the years. Some of the material that follows has previously appeared in these pages (in 2017)—in a three-part essay on impresario Lincoln Kirstein, who cofounded the New York City Ballet with George Balanchine—but much of it is brand new.

BY 1933, Lincoln Kirstein’s long-simmering search for a way to establish a classical ballet company in the United States picked up steam and intensity. His interest in the ballet had initially quickened on his various trips to Europe as a teenager, when he’d seen Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. That same year, 1929, with Diaghilev’s death, the ballet world had become rent by factions. A number of émigré artists had been trying to lay claim to his mantle, and to find venues, patrons, and, they hoped, companies that might make their existence less precarious.

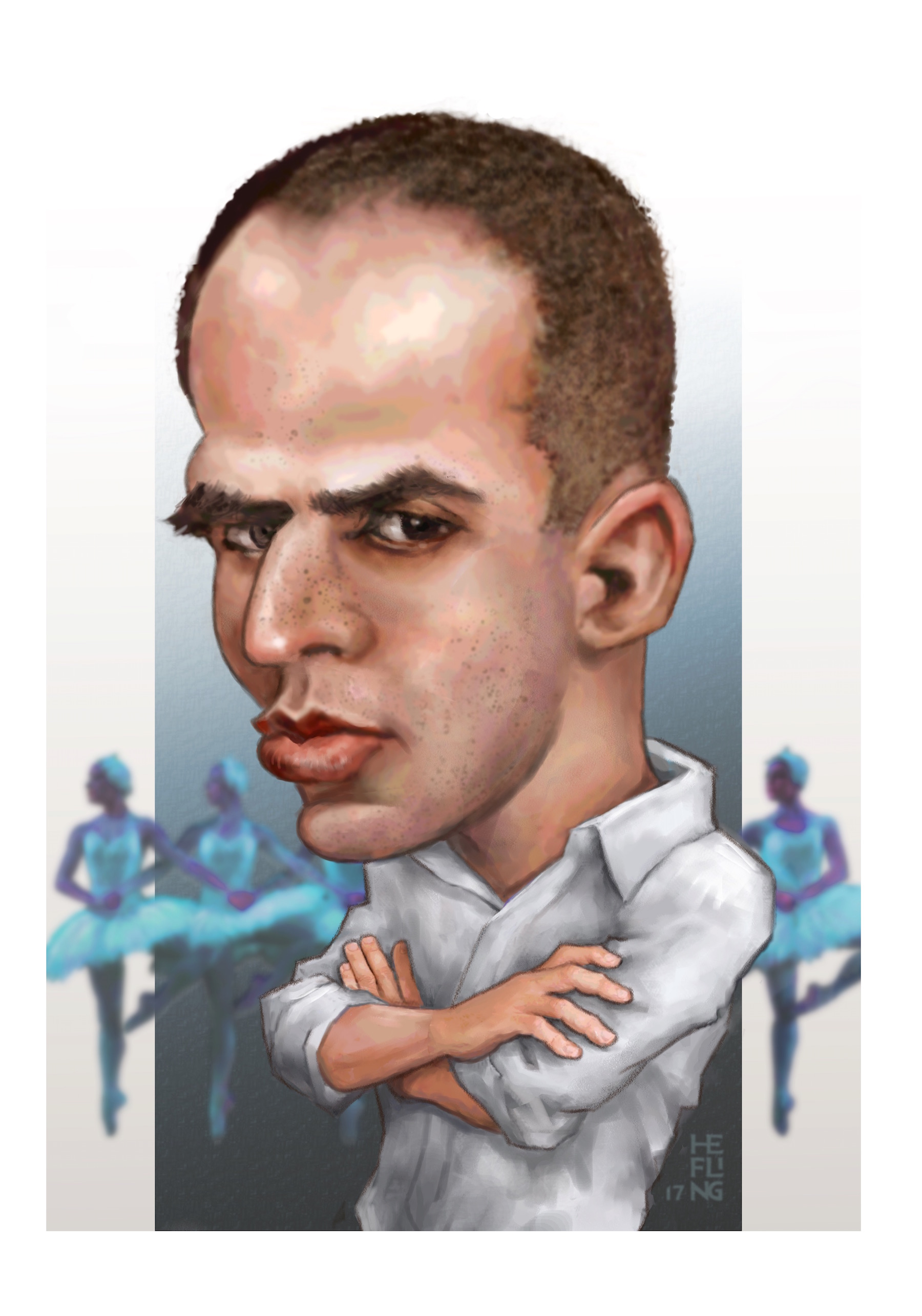

George Balanchine, who’d been Diaghilev’s last important choreographer, succeeded in putting together a group called Les Ballets 1933, a young company of some fifteen dancers, including Toumanova, Derain, and Roman Jasinski. None of this would have come to pass had it not been for the events of a decade earlier, when Vladimir Dimitriev, a former baritone in the Mariinsky opera company, successfully engineered exit visas from the Soviet Union for a small group of artists, the so-called Soviet State Dancers. Among them were Balanchine, Tamara Geva, his first wife, and the ballerina Alexandra Danilova, who would become his “unofficial” second wife.

George Balanchine, who’d been Diaghilev’s last important choreographer, succeeded in putting together a group called Les Ballets 1933, a young company of some fifteen dancers, including Toumanova, Derain, and Roman Jasinski. None of this would have come to pass had it not been for the events of a decade earlier, when Vladimir Dimitriev, a former baritone in the Mariinsky opera company, successfully engineered exit visas from the Soviet Union for a small group of artists, the so-called Soviet State Dancers. Among them were Balanchine, Tamara Geva, his first wife, and the ballerina Alexandra Danilova, who would become his “unofficial” second wife.

Kirstein went up to Hartford to see his friend Chick Austin, the youthful head of the prestigious Wadsworth Athenaeum, who showed him the half-completed new International Style addition to the museum. Kirstein noted in his diary that “his little auditorium is perfect for small ballets.” Austin, like Kirstein, was a serious advocate of the arts and an audacious innovator. As director of the Athenaeum, he’d transformed Hartford’s reputation as the stodgy headquarters of the insurance business into an important center of cultural ferment. Kirstein knew that, although Austin was married, his erotic preference was homosexual, and he hinted to Kirstein, who also preferred men, about having recently indulged in “some highly irregular pleasures,” saying that he’d tell him more some other time.

Martin Duberman’s latest book is titled Reaching Ninety. His forthcoming collection, The Line of Dissent, will be published by The G&LR.