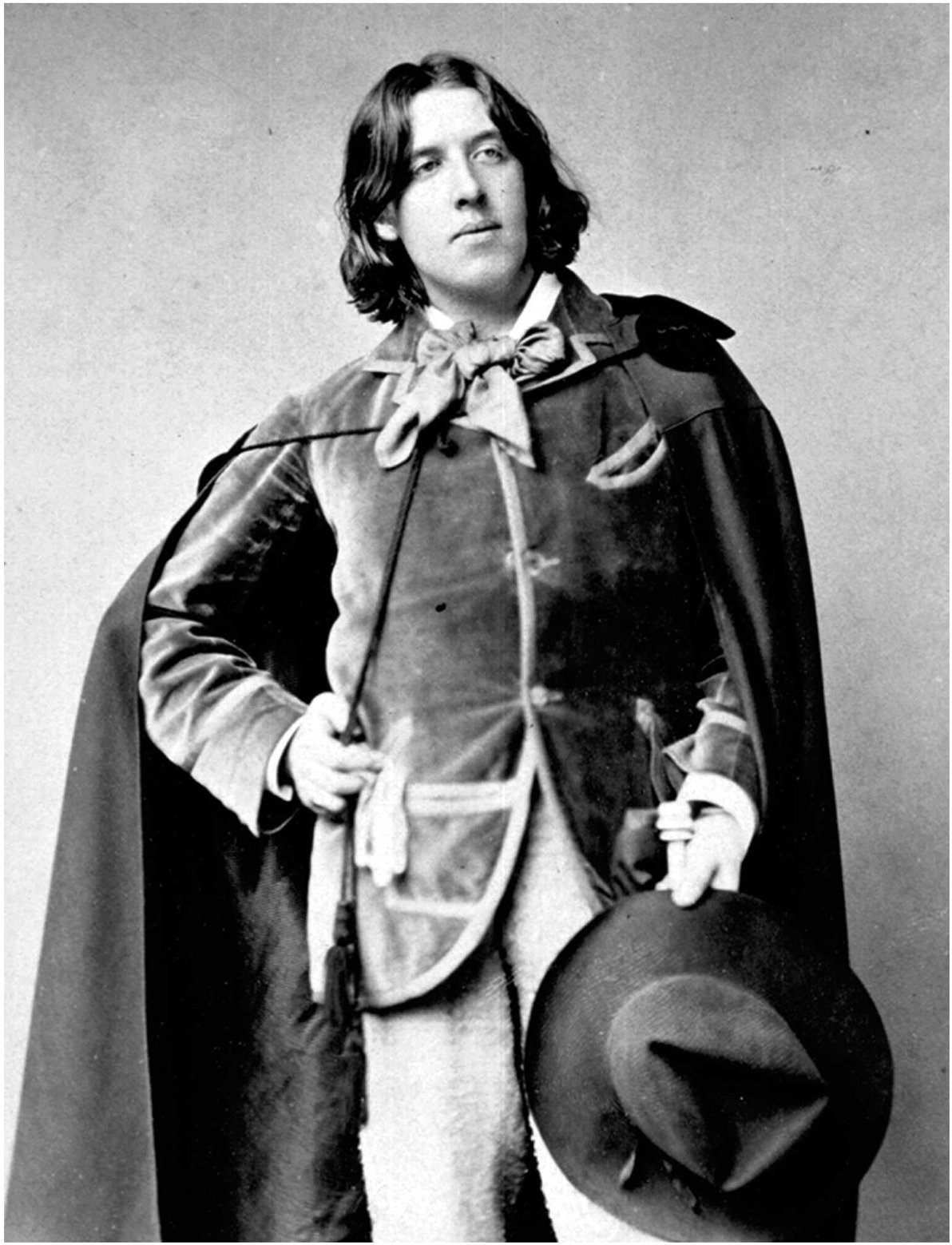

IN FULFILLMENT of his gauntlet-throwing declaration, in A Woman of No Importance, that “A man who can dominate a London dinner-table can dominate the world,” Oscar Wilde did just that—if by “world” we mean the view from the chic Hotel Café Royal where he held court, polishing his epigrams, sipping champagne, and gazing besottedly at his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas. If he were alive today, he’d conquer the Twitterverse, too, no doubt.

In a very real sense, he has: his epigrams and aperçus are everywhere on social media. A Google search for his name turns up 26 million hits. The bon mots that have made him the most-quoted English-language author after Shakespeare are as wildly popular now as they were in 1895, when An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest were playing to sold-out houses in London’s West End. Wilde, like Shakespeare, combines deathless style with ageless insights—about morals and manners, culture and nature, artifice and authenticity, society and the individual, and, of course, love and sexuality.

Juxtaposed with the issues of our day, Wilde’s “phrases and philosophies” (as he called them) offer a bracingly fresh, and amusingly oblique, angle of attack on the moral crusades, social norms, identity politics, and ideological tribalism of the 21st century, while reminding us just how Victorian we still are—and just how prescient Wilde was. His wit, Wilde scholar Regenia Gagnier remarked to the BBC, is “extremely modern in that it breaks up the ideology, it breaks up the fixed ways of seeing.”

A quip like “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about” (from The Picture of Dorian Gray) strikes a responsive chord at a moment when we weigh our social status in likes, shares, and retweets.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and author of four books. His most recent is the biography Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.