EDWARD GOREY’S BOOKS are—to borrow a line from an early, fretful review of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are—not the sort of thing that should be left “where a sensitive child might find it to pore over in the twilight.” His best-known book, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, is a mock-moralistic ABC that plays the deaths of little innocents for laughs: “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs/ B is for Basil assaulted by bears…”

Gorey, who died in 2000 at the age of 75, was the author and illustrator of a hundred-odd darkly droll little picture books with titles like The Fatal Lozenge, The Deranged Cousins, and The Blue Aspic. Although he grew up in Depression-era Chicago and lived most of his life in Manhattan, first-time readers often assume he was a denizen of gas-lit London. He set his stories in some vaguely Victorian-Edwardian England and illustrated them with 19th-century engravings that turn out, on closer inspection, to be pen-and-ink drawings—marvels of obsessive crosshatching. Inspired by Agatha Christie, Edward Lear, penny dreadfuls, Dracula, Max Ernst’s Surrealist “collage novels,” the silent-movie melodramas of Louis Feuillade (especially his crime thriller Fantômas), and those grisly cautionary tales the Victorians inflicted on their petrified tots, Gorey’s work defies genre. No matter how many hyphenated categories we dream up—ironic-gothic? camp-macabre? Victorian-Surrealist?—none quite fits.

One thing’s for sure: a pre-Stonewall gay æsthetic pervades much of his work, and a queer subtext runs beneath the surface of a number of his books. Now, after decades of invisibility, the gay Gorey is coming out of the shadows; scholars and reviewers are coming to terms with these aspects of his life and art. Well, most critics, that is: for some of the reviewers who weighed in on my Gorey biography, Born to Be Posthumous, queer theorizing about Gorey remains somehow déclassé—at best reductionist, at worst Norman Bates-level voyeuristic. Robert Gottlieb, the legendary editor who reviewed the book for The New York Times Book Review (12/31/18), epitomizes this mindset: “For Dery the mystery that matters most is that of Gorey’s sexuality—he gnaws away at it relentlessly throughout the 400-odd pages of his narrative,” he wrote. “Was Gorey straight? Not very likely. Was he gay? Probably, but not actively.” And that, for the last living member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, is that.

Does it matter that Gorey, who struck everyone who met him as a textbook example of pre-Stonewall flamboyance—pricking wit, fluttery hand gestures, floor-sweeping fur coats, fingers dripping with rings—was determinedly evasive about his sexuality, insisting that “I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly”? Or that he claimed to eschew sex altogether? Should we care whether Gorey’s lifelong celibacy (“I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something”) was a languid æsthetic pose or something darker, a post-traumatic recoil from his one and only sexual experience, almost certainly a same-sex one, which happened in high school? Gottlieb waves away Gorey’s admission, to a very few friends, that he found the experience so distasteful that it put him off sex for the rest of his days (or so he claimed).

I believe we should care about Gorey’s sexuality, not just because it sheds a revealing light on his inner life, but because he’s one more example of the centrality of queer culture’s contribution to the arts. Of course, it illuminates his work, too. Consider Gorey’s fascination with the Victorians, synonymous in the modern mind with sexual repression. Think of his use of genre conventions lifted from Gothic novels, murder mysteries, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and the darker Dickens: the sidelong glances, the stealthy meetings, the general sense that things are not as they appear; of whispered confidences and melancholy recollections of “the miseries of childhood.” Isn’t it possible, just maybe, that Gorey’s art had something to do with aspects of himself that he kept hidden from public view? “Every now and then someone will say my books are seething with repressed sexuality,” he conceded, in one interview.

§

The critic Thomas Garvey, from whom we get the useful concept of “the glass closet”—“that strange cultural zone” inhabited by public figures, like Gorey, who “simultaneously operate as both gay and straight”—points out that “Gorey kept perfectly mum about his true nature to the press; he only spoke about it in his art.” As I note in my book, interviewers and reviewers in the Gottlieb camp were happy to play along: media coverage of Gorey was consistently—and a little too insistently—oblivious to the gay themes in his art, the gay influences on his æsthetic, and the gay origins of his flamboyant persona.

The Gorey we meet in perfunctory newspaper profiles is a Dr. Seuss for Tim Burton fans; little is made of the gay subtext of his art and life, presumably because mentioning children’s literature and homosexuality in the same breath stirs dark suspicions in the American mind, especially when the subject is an eccentric old gent who seems to enjoy killing off children (in his stories, at least). If such articles are to be believed, then “Gorey wasn’t necessarily gay, even though he was a life-long bachelor who dressed in necklaces and furs,” Garvey writes. “He was just asexual, a kind of lovable eunuch who spent his spare time petting his cats down on the Cape when he wasn’t drawing his funny little books.”

But, as Garvey notes, whether you believe they’re “seething with repressed sexuality” or not, there’s something queer about those funny little books. In The Other Statue (1968), Dr. Belgravius, a Gorey alter ego in beard and fur coat, shares an unspecified “curious discovery” with his nephew Luke Touchpaper while they’re ogling the buttocks of a male statue, naked but for a strategically placed fig leaf. In The Fatal Lozenge (1960), a collection of quatrains that are by turns disquieting, macabre, and perversely funny, a proctor “buys a pupil ices,/ and hopes the boy will not resist/ when he attempts to practice vices/ few people even know exist.” The creepy proctor extends a groping hand toward the schoolboy who laps, unaware, at his ice. Likewise, in Gorey’s adverbial abecedarium, The Glorious Nosebleed (1975), a little boy stares, bemused, at a bowler-hatted man flinging his coat open with demented glee. Caption: “He exposed himself Lewdly.” We begin to wonder if Gorey’s early, unhappy encounter involved an older man.

For those in the know, Gorey’s work is full of Easter eggs—coded references to gay history, culture, or that elusive thing, the gay sensibility. In The Gilded Bat (1966), Gorey’s gothic valentine to the Diaghilev era in ballet, the prima ballerina and the Baron de Zabrus chat amid the Baron’s retinue, a gaggle of sleek young men who have eyes only for each other—a nod to Diaghilev’s habit of appearing in public with his male dancers, and of having affairs with a good many of them.

For those in the know, Gorey’s work is full of Easter eggs—coded references to gay history, culture, or that elusive thing, the gay sensibility. In The Gilded Bat (1966), Gorey’s gothic valentine to the Diaghilev era in ballet, the prima ballerina and the Baron de Zabrus chat amid the Baron’s retinue, a gaggle of sleek young men who have eyes only for each other—a nod to Diaghilev’s habit of appearing in public with his male dancers, and of having affairs with a good many of them.

In The Blue Aspic (1968), Gorey’s tale of opera fandom taken to diva-stalking extremes, the prima donna Ortenzia Caviglia’s revival of Elagabalo is “cut short when the authorities” have “the curtain rung down on the triple-wedding scene.” Elagabalo, for those not up on their opera trivia, is the Baroque composer Francesco Cavalli’s treatment of the life of the Roman emperor of the same name, who scandalized all of Rome by marrying another man, a well-endowed athlete. According to the Augustan History, Elagabalo was notorious for “living in a depraved manner and indulging in unnatural vice with men”: prostituting himself in drag; appointing to high offices “men whose sole recommendation was the enormous size of their privates”; and—cover your ears, Mike and Mother Pence—making “indecent signs with his fingers.”

When Gorey lets slip his “true nature,” as Garvey calls it, he can be dog-whistle subtle (as in his allusions to Diaghilev and Elagabalo), campy, poignant, or furious.

Campy: as in his Roaring Twenties parody of our grandparents’ porn, The Curious Sofa (1961), in which only the men’s attributes are winkingly euphemized (“Albert, the butler, an unusually well-formed man of middle age, joined them for another frolic”) and gay romps are recounted with a matter-of-fact relish that, for its time, is beyond bold: “Looking out the window she saw Herbert, Albert, and Harold, the gardener, an exceptionally well-made youth, disporting themselves on the lawn.”

Poignant: as in the scene in Gorey’s wordless meander through a haunted mansion, The West Wing (1963), in which we encounter a bearded Gorey lookalike standing naked, his back to us, clasped hands covering his tush—the seat of his desire, as it were. The sense of vulnerability and loneliness, of unrequited love, of never venturing beyond the adolescent crush, even in middle age, is palpable. He “buried a lot of information about himself in the art,” said Maurice Sendak, who ran into Gorey now and again on New York’s commercial illustration scene.

Furious: as in the nightmarish little vignette in The Listing Attic where Gorey depicts capering young men encircling a statue, brandishing torches. On top of the statue—the famous bronze likeness of John Harvard in Harvard Yard—a terrified figure cowers as one of the revelers strains with outstretched torch to set him on fire. Gorey writes:

Some Harvard men, stalwart and hairy,

Drank up several bottles of sherry;

In the Yard around three

They were shrieking with glee:

“Come on out, we are burning a fairy!”

This is the Harvard of Gorey’s undergraduate years (1946-’50); the Harvard where he first encountered other cultured, cuttingly funny gay men, among them Frank O’Hara (for two years his roommate) and John Ashbery, and where he discovered some of his most enduring literary inspirations, nearly all of them gay or lesbian, such as the 1920s and ’30s novelists Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett. It’s also the all-male Harvard that expelled two students engaged in what O’Hara’s biographer Brad Gooch calls “illicit activities,” driving one of them to suicide. His scarifying limerick, in which the “stalwart and hairy” have their revenge on the fairy, gives Gothic shape to the free-floating homophobia of the times, weaponized by Senator McCarthy in his witch hunt for gay men lurking in the highest levels of government.

§

All of which is to say that reviewers who pooh-pooh the relevance of Gorey’s secretive sex life deprive us of psycho-biographical and art-historical insights that go to the heart of who he was and what he was up to. In its furtive, sotto-voce way, Gorey’s work is in conversation with gay history, gay literary influences, and, now and then, the gay-straight tensions of his time. By dismissing critical interest in his debt to queer culture and the gay æsthetic, such critics collude in the erasure of both—and of the queerness all around us, hiding in plain sight.

Consider two of the Victorian genre traditions that are Gorey’s home bases, the Gothic and nonsense verse, which he sometimes hybridizes into Gothic nonsense and at other times transposes into the ironic key of camp Gothic. A precocious child who taught himself to read at three-and-a-half, Gorey took to the Gothic immediately, plowing through Dracula and Frankenstein before he was out of short pants. By seven, he’d read Lewis Carroll’s Alice books—the founding texts of Gothic nonsense, its ugly Duchesses and nightmare Jabberwocks brought to life by Tenniel’s disquieting illustrations (a seminal influence on Gorey’s drawings).

Little wonder that he made the genre his own: the Gothic, with its nocturnal inversion of day-lit “normalcy,” its pagan desecration of family values, its uncanny doubles and sinister twins and split personalities, its unspeakable secrets buried in the basement or locked away in the attic, has offered gay and lesbian artists and writers a symbolic language tailor-made for lives that, for much of recorded history, have been double lives. Putting its spookhouse gimmicks to subversive use, queer authors have given Gothic shape to a welter of conflicting feelings: their fear of exposure, their fantasies of being proudly out, their craving for assimilation, their embrace of their outsider status, their self-love, their self-loathing.

Think of The Talented Mr. Ripley by the lesbian writer of noir thrillers Patricia Highsmith. The suave sociopath Tom Ripley murders Dickie Greenleaf, the Gatsbyesque trust-funder who shrinks from his affections, then assumes Dickie’s identity, savoring his bespoke suits and “grain-leather shoes.” He’s Tim Gunn’s idea of a doppelganger. Think, too, of the Southern Gothic elements in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and Suddenly Last Summer: Blanche DuBois, a female female impersonator in the Tallulah Bankhead mold, haunted by the memory of her gay husband, who committed suicide after she caught him in flagrante with another man; Sebastian Venable, torn limb from limb and cannibalized by Spanish street urchins after his appetite for rough trade offends the locals.

Think, finally, of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Written the year Oscar Wilde was convicted of sodomy, the novel that fixed the image of the Blood Count in the mass imagination is shot through with homoeroticism and gay symbolism. Stoker, who knew Wilde, was almost certainly gay, however closeted. He had a serious crush on Walt Whitman, to whom he sent “passionate letters,” as David J. Skal puts it in his cultural history of horror films Screams of Reason: Mad Science in Modern Culture (1998), swoony missives “expressing his desire for an ecstatic, androgynous fusion.” Skal reads Stoker’s novel as “an all-male fantasy in which the women are merely a conduit for displaced homoerotic impulses.” Queer theorists make much of the scene in which the Count rebuffs the Brides of Dracula just as they’re about to make a meal of his houseguest, the delectable young Jonathan Harker: “How dare you touch him, any of you? … Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me!” (Francis Ford Coppola takes the homoerotic frisson of the book to delirious heights in his 1992 re-telling in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The scene in which Gary Oldman’s Count, an undead drag queen in Mommie Dearest cold cream and Baroque beehive, slithers all over Keanu Reeves’ Harker, obscenely licking the blood from his shaving razor, is camp heaven.)

Like the Gothic, with its inversion of Victorian manliness, muscular Christianity, rationalism, and earnestness, the nonsense verse and prose popularized by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll were likewise a natural fit for “inverts,” as gays and lesbians were known in the medico-legal jargon of the late 19th century. Both æsthetics challenged the social order, mocking Victorian truisms about gender, sexuality, class, religion, morality, progress, and childhood.

Lear’s influence on Gorey was profound; clearly, he felt a deep sympathy for the Victorian fantasist, an outsider whose work celebrates outsiders. Rendered with exquisite lyricism, his illustrations for The Jumblies (1968) and The Dong with the Luminous Nose (1969) are not only among his best decorations for other peoples’ books, they’re also among his quirkiest: the egg-shaped, spindly-legged manikins scurrying about in both are utterly unlike the dour Victorian-Edwardians who populate Gorey’s own titles.

Gorey followed Lear’s lead into the darker corners of the unconscious, giving the limerick and the alphabet an ironic-gothic spin and creating a funny-grotesque bestiary all his own, teeming with Fantods and Figbashes, Wuggly Umps, and Ombledrooms. Interspecies relationships—“unnatural” couplings—are common in both artists’ work: in Lear, the Owl and the Pussycat, the Duck and the Kangaroo; in Gorey, the boater-hatted Emblus Fingby and the Osbick Bird (The Osbick Bird, 1970), the “beautiful young man” Hamish and his pride of lions (The Lost Lions, 1973).

Beyond those artistic similarities are more intriguing parallels between the two men’s lives. Lear, too, was traumatized for life by a sexual encounter. According to Inventing Edward Lear (2018), by Sara Lodge, his 23-year-old brother and nineteen-year-old cousin molested him when he was ten. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was, like Gorey, unlucky in love and lived alone. Also like Gorey, his crushes went unreciprocated. He fell passionately in love with a dear friend, another man, who wasn’t that way inclined. Their friendship survived, but Lear spent forty sorrowful years tortured by one-sided passion.

It’s not surprising, then, that his nonsense, all surrealist whimsy on the surface, often has a melancholy underside. In The Dong with a Luminous Nose, the Dong—a forlorn little chap in a billowing white overcoat, as drawn by Gorey—falls head over heels for the Jumbly Girl, only to have his heart broken when she sails away. He spends the rest of his nights seeking—in vain—“to meet with his Jumbly Girl again,” searching high and low by the light of his luminous nose. Circumstances conspire against the Dong, as they did against Lear’s “unnatural” love.

“If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point,” said Gorey. “I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children—oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that’s true, there really isn’t. And there’s probably no happy nonsense.”

§

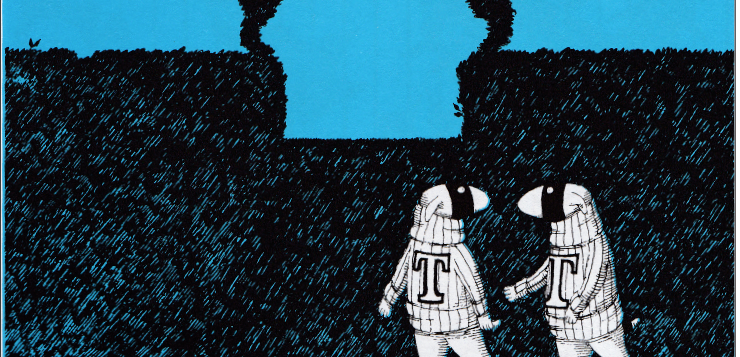

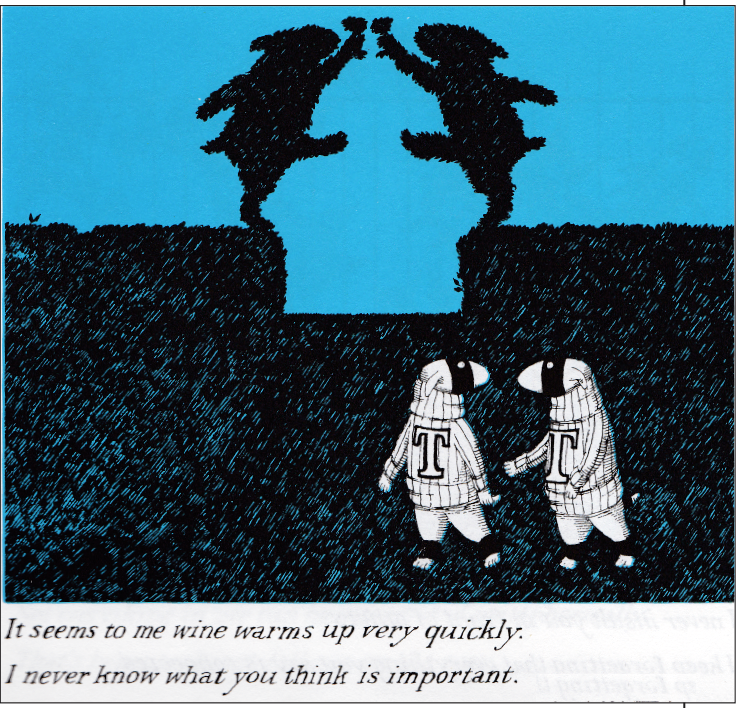

L’Heure Bleue (1975), Gorey’s bittersweet valentine to his last crush, is somber nonsense. It’s also an achingly beautiful contribution to the secret history of queer lives, though the book’s subtext went unnoticed when it first appeared. Published under Gorey’s Fantod Press imprint, L’Heure Bleue is a gorgeous book, printed in black and a lush cerulean blue. The title derives from the French term for that fleeting period in early dawn or late dusk when the indirect light of the sun paints the sky a shimmering blue. It’s a time of day rich in poetic associations: ambiguity, ambivalence, wistfulness, time slipping away.

The book was inspired by a tour Gorey and a darkly handsome young man named Tom Fitzharris made of the islands off Scotland’s west coast. At some point, Fitzharris, who was straight, ran off with a woman, leaving Gorey to soldier on alone. Somewhere between Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage, Waiting for Godot, and those blue-tinted day-for-night scenes in silent movies, it’s a plotless series of vignettes. We see two cartoon dogs living their lives together; they wear matching cable-knit sweaters emblazoned with “T” (for “Ted” and “Tom”). Each panel is accompanied by a comment and an apropos-of-nothing response, lines of cryptic dialogue lifted, most likely, from remembered conversations and Gorey’s letters to his friend. Here we see the couple, strolling alongside topiary versions of themselves. “It seems to me wine warms up very quickly.” “I never know what you think is important.” In another scene, they’re standing in front of a wrought-iron fence on which the ivy is making arabesques. “I never insult you in front of others.” “I keep forgetting that everything you say is connected.” The inadequacy of language and the impossibility of communication is a theme, as it was in Gorey’s correspondence with Fitzharris.

L’Heure Bleue is a nocturne on love and loneliness, a reverie about all that could have been, confected from what was. Yet despite its blue mood, Gorey’s book has given heart to gay men like my friend Ted Abenheim, who said in a message: “I was introduced to Gorey in the early ’70s when I was coming to terms with my sexuality. It wasn’t until I read L’Heure Bleue that I put two and two together: this was about a same-sex couple and could possibly be from Gorey’s experience. Then the æsthetic in all of his books started falling into place as I was putting together my own perceptions of gay life and how I fit in.”

L’Heure Bleue is a nocturne on love and loneliness, a reverie about all that could have been, confected from what was. Yet despite its blue mood, Gorey’s book has given heart to gay men like my friend Ted Abenheim, who said in a message: “I was introduced to Gorey in the early ’70s when I was coming to terms with my sexuality. It wasn’t until I read L’Heure Bleue that I put two and two together: this was about a same-sex couple and could possibly be from Gorey’s experience. Then the æsthetic in all of his books started falling into place as I was putting together my own perceptions of gay life and how I fit in.”

Ted’s story made me think of Jesse Green’s observation in his Times Style Magazine article “The Gay History of America’s Classic Children’s Books”: “The authors of many of the most successful and influential works of children’s literature in the middle years of the last century—works that were formative for Baby Boomers, Gen-Xers, Millennials and beyond—were gay. At a time when those writers wouldn’t dare … walk hand in hand with a lover, … they won Caldecott and Newbery Medals for books that, without ever directly speaking their truth, sent it out in a secret language that was somehow accessible to those who needed to receive it.”

Critics like Gottlieb are unmoved by the revelation that the editors of Ascending Peculiarity, a collection of Gorey’s interviews, took care to expunge his answer to the pointed question, “What are your sexual preferences?” “I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t identify with it much.” By this he meant that, while his social style left little doubt about his “preferences,” he didn’t share the assumption, widespread among gays and lesbians who came of age after Stonewall, that his sexuality defined his identity. “What I’m trying to say,” he told the interviewer, “is that I’m a person before I am anything else.”

Kevin McDermott, who was working for Gorey’s sometime publisher Andreas Brown during the editing of Ascending Peculiarity, told me he was “disheartened” by the deletion of those two lines. As a gay man who was much younger than Gorey, McDermott thought it was “a brave thing he was doing there, as a man of that generation—finally saying it. And then he qualified it, which I think is totally appropriate because that’s probably true; when he said he was asexual, I’ll take him at his word.” Why Brown excised it McDermott has no idea. Maybe he was “concerned that Edward wouldn’t be taken seriously as an artist because he was a gay artist,” he speculates.

It’s only two lines, but that’s how gay history is rubbed out: with a million little erasures.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and author of four books. His most recent is the biographyBorn to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.