Originally published on the art fuse.

Despite the demise of print publications, Boston’s own Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide (G&LR) just published its 159th issue. The magazine began in 1994 as the Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review. In 2000, “Harvard” was dropped from its name and “Worldwide” added. In its early years, the G&LR was printed in black and white, gradually evolving to full color in 2011.

The glossy bimonthly journal features erudite essays from queer historians, scholars, writers, and political figures investigating relevant history, politics, and culture as well as artist interviews and reviews of books, exhibitions, movies, and plays. Organized as a nonprofit, G&LR currently has a print run of 11,000 per issue and is supported by 8,000 subscribers and 750 donors.

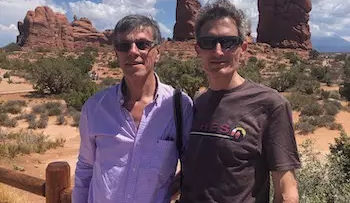

Driving the vision is editor-in-chief and founder Richard Schneider. He received a PhD in sociology from Harvard in the early ’80s and founded the Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review (first as a volunteer in 1994, full-time since 1999), and continues as editor today.

Originally, he was recruited to produce a newsletter for the Harvard Gay and Lesbian Caucus alumni organization, where he learned editing and desktop publishing. Almost immediately they realized it could be a national magazine. As the enterprise developed, it became independent of Harvard in 2000.

In a 1998 feature in the New York Times, Schneider spoke about his initial aspirations: “In 1993 there was nothing in the gay world corresponding to the New York Review of Books or the Times Book Review or Atlantic Monthly or the New Yorker that featured intelligent essays,” he said. “There was a huge niche or vacuum in gay and lesbian letters which I hope we somewhat filled.”

From its inception, trenchant writing, and interviews from such literati as Edmund White, Barney Frank, Jill Johnston, and Jewelle Gomez differentiated the magazine with its focus on high culture. “It is our intellectual journal.… If you want to deal with scholarly intelligent arguments, there’s really no place else we can publish,” writer/activist Larry Kramer was quoted as saying in that same New York Times article from 1998.

Over the years, astute analysis of literary icons has been a hallmark. The work of Thom Gunn, Hart Crane, Truman Capote, and Oscar Wilde as well as Susan Sontag, Eileen Myles, Leslie Feinberg, and Willa Cather has been featured.

In a recent phone conversation, Schneider filled me in on the history, philosophy, and plans for the journal. Currently, donations and subscriptions each account for about 40 percent of the income, while advertising fills in the last 20 percent. Readership is predominately male, 70 percent are over 60 years old with 66 percent holding an advanced degree. The renewal rate is very high.

Part of its continuing success, he feels is that the “somewhat older readership is still committed to hard copy. We have very loyal readers; many have been with us since the beginning. Some save every issue. The look of the magazine is still similar to what it was a long time ago — typeface, layout, design,” so it remains “favorite comfort food” for intellectually engaged readers. As well, much of the content online is behind a paywall, further encouraging print subscriptions.

Issues are organized thematically, sometimes intentionally and other times organically given what material is in house. An upcoming issue will focus on the 50th anniversary of the American Psychiatric Association delisting homosexuality as a mental illness.

More than 1,400 writers have been featured in G&LR’s uninterrupted run over the last three decades. As an editor, Schneider finds “working with every writer is different. Every story that we run is in itself a story in its own way.” He tries to be as “not heavy handed as possible to make a piece work. I run everything by the author, and we will negotiate a little bit.”’

One steadfast presence has been Andrew Holleran, who is having a critical resurgence at the age of 80 with his latest acclaimed novel, The Kingdom of Sand, a melancholic depiction of isolation, despair, and desire in older gay men. His first essay in G&LR (1994) was taken from a speech he gave at Harvard detailing his coming of sexual age in Greenwich Village in the ’70s. Since then, Holleran has written over 100 articles.

Celebrating the magazine’s 25th anniversary in 2019, Holleran wrote: “We’ve all seen many of our favorite mainstream magazines shrink if not disappear, which makes me all the more grateful for the G&LR. A writer has one basic dream: to see his or her words in print.… And I’m always thrilled when someone mentions a piece I’ve written because one forgets that one does reach people, people we may never hear from, but who are out there — in the dark. Quite literally, being published in the G&LR has been a reward in itself — it’s kept this writer going in the horror vacui of the digital age.”

Schneider loves working with the author on features: “He writes very quickly, producing 2,500-3,000 words. He likes to work (on editing) over the telephone, so I get to talk with Andrew Holleran for an hour or two every couple of months.”

Another favorite writer is Laurence Senelick, theater artist and professor at Tufts University. Schneider calls him “a fabulous scholar and historian who does extensive research on odd little social customs.” In a 2021 essay, he elucidates the slang catchphrase, “Whoops, M’dear” as code words for men cruising other men in the early 20th century.

I too am fortunate to be supported by G&LR; my published pieces include commentaries on John Cage, Keith Haring, Peter Hujar, and Sarah Schulman, along with interviews with Alison Bechdel, Janis Ian, Bill T. Jones, and Tim Miller. Most recently, I profiled trans filmmaker Angelo Madsen Minax. As an editor, Schneider is always open to ideas and he wields an appreciated editing scalpel that cuts for focus and clarity.

Drawing upon its treasure trove of queer writing, G&LR published two compilations of past articles. The first, In Search of Stonewall (2019), coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, explicating historical precedents, realities, and the impact of the protests. First-person eyewitness reports detail the 1969 events often credited as the beginning of the LGBTQ civil rights movement.

As well, foundational essays from 1995 featured Harry Hay alongside Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, founders of Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis respectively — two West Coast groups organized in the ’50s to support safe spaces and political action on behalf of queer people. Telling, and clarifying, forgotten histories remains central to the magazine decades later.

The second book, Casual Outings, (2021) celebrated Charles Hefling’s illustrated portraits accompanying profiles on 27 artists such as Marcel Proust, Vita Sackville-West, Frida Kahlo, Yukio Mishima, Lorraine Hansberry, Leonard Bernstein, and Langston Hughes. In his introduction to the collection, Schneider writes, “Casual Outing thus refers to the fact that we are in some sense “outing” people who tried to hide their sexuality at least some of the time.” This is essential truth-telling, especially when families, estates, and biographers so often obfuscate complex truths.

One reprint in development is with historian Martin Duberman, now in his 90s, revisiting 14 of his pieces for the G&LR (starting in 1999) with three additional essays on his customary exploration of the intersection of LGBTQ and leftist politics. Schneider is also hoping to work with Holleran on a compendium of profiles of pre-Stonewall writers from his prodigious contributions.

Collaborating with Schneider on the operational side of the publishing endeavor is his partner of 23 years, Stephen Hemrick, who is the publisher. After recent Supreme Court decisions, they are planning a civil ceremony wedding later this month.

John R. Killacky is the author of because art: commentary, critique, & conversation (Onion River Press).

John R. Killacky is the author of because art: commentary, critique, & conversation (Onion River Press).