Even after the first years following Stonewall, Albany’s gay subculture was still distinctly closeted. Chapters of Gay Liberation Front (GLF), Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), and Gay Maoists had started up on campus my freshman year, where a few men were out, but most, like I, were closeted

When I first walked into G.J.’s Gallery, a neighborhood bar in Albany, NY, I found myself in the bohemian underworld I had longed for. Dark, smoky, Rolling Stones on the jukebox, a long bar stretched from the front door halfway through the room—opposite were booths, and the smell of Mary Jane mixed with cigarette smoke lingered above.

I became familiar with the bar’s clientele: writers and painters from the neighborhood, some drug pushers, some gay men, and occasional college students like me, who could frequent bars when New York state’s legal drinking age was eighteen. The crowd was almost exclusively men, some smoking joints in the bathroom, as dealers peddled acid, speed, Quaaludes, and grass.

I usually went with two friends, Doug and Ritchie; we three were on the editorial board of the campus lit magazine. Doug had recruited Ritchie and me to join his fraternity; we were poets—poetry was popular in those days of America’s counterculture—so we hung out at G.J. to mingle with other artsy folks. My actual purpose was to find men for sex; If asked, I’d assert I was “experimenting with my bisexuality.”

Looking back some fifty years, I am amazed at my picking up on the subtle clues of men signaling sexual interest in each other, and my brazenness leaving G.J.’s accompanied by a total stranger in front of my fraternity brothers. One evening, a guy asked me if I wanted to go to the Central Arms. He explained it was a gay bar, and “with your good looks you’ll be popular.”

The Central Arms, on a decrepit commercial street, was also pre-Stonewall, with no windows or signs outside and a peephole in the front door. You pushed a button, someone looked through the peephole, and if you passed muster, you were buzzed in.

There was a mirror behind the long bar, which guys used to check each other out. Strings of Christmas lights twinkled around the mirror and walls. The jukebox played mostly The Supremes, and most of the guys were very “feely” and drunk all the time, so I often got groped while simply ordering a beer.

I went home with many men: one working at a hardware store, one a seminarian, one a florist; then a groundskeeper, hairdresser, and a state office worker. All of them older—I was nineteen. They were all either alcoholics, or budding alcoholics. I always gave them a false name and a phony number, and never saw them a second time.

After I found other ways to find sex—cruising in Washington Park, calling numbers left in public toilets, cruising the basement stacks in the university library—I stopped going to the Central Arms. During those months, I completely came out; first to myself, then my friends. After my release from the closet, my heart began to open. I wanted to have a lover and even become genuine friends with other gay men.

By the mid-1970s I was fully out, an in-your-face gay activist, or what the straight press called a “militant homosexual.” As a graduate student in West Germany, living with my first lover, Dennis, with whom I expected to spend the rest of my life— we had an open relationship, though I was the more sexually voracious one. We both wrote poetry and, with three German students, published a small, semi-annual poetry magazine. Over summer and winter breaks, we traveled a great deal around Europe and the US.

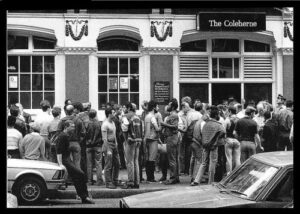

We visited Britain in 1977, staying at Redfield’s, a gay hotel in Earls Court which, in those days, was a famous London gay neighborhood. Immediately, a few streets from our hotel, we came across a popular gay pub, called the Coleherne, which then catered to the Levis and leather crowd. With a long history as a bohemian pub, it became London’s preeminent leather bar in the 1970s and 1980s, attracting international celebrities like Freddie Mercury, Anthony Perkins, Rupert Everett, Ian McKellen, and Derek Jarman.

The Coleherne was huge with a “J”-shaped bar. On the short side of the “J,” a crowd hung out in full leather, and on long side, the “Levis” side, the crowd was thicker, more sexually charged, with English spoken in English, Scottish, Irish, American, and Australian accents. The cruising was intense and heavy. A narrow passage space maintained between the bar and the crowds allowed guys to circulate.

I’d survey the crowd, looking for the guys I found attractive or interesting looking. I’d approach each guy and talk with him for a while. Sometimes a guy would offer to buy me a lager, or I’d do the same. After a while one of us would make an excuse to leave and resume circulating through the crowd. When closing time came, I’d ask one of “my” guys to go home with me. If he turned me down, I’d ask the next guy on my list. I never left alone, and always with someone I definitely wanted.

On my very first visit I went home with Ken, a painter from working-class Bradford in West Yorkshire. He was a redhead and spoke with such a thick Yorkshire accent that I had to ask him to repeat almost everything he said. Although we never had sex with each other again, Ken became my best friend; I would make many visits to London over the years to stay with him, and eventually my ears adjusted to his West Yorkshire accent.

I met many men from all over the world in the Coleherne and became friends with a number of them. Some of these friendships endured for years, but all of these friends, except for Ken, died either from AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s, or from age in the past two decades. Ken is now over eighty, still in London, still painting. In retirement, we are both too poor to visit each other (Ken used to visit me when I lived in San Francisco, then in Boston, and then again back in San Francisco.) We remain in regular contact by mail, email, and Facetime.

My most poignant experience at the Coleherne was meeting Derek Noakes, an Australian working for a travel agency in London. This was the summer of 1979; I was leaving Tübingen to move to San Francisco. I was again on my own, taking the entire summer to get to the West Coast, stopping to visit friends along the route. My first stop was London, planning when ready to fly standby to Boston. I had already shipped my stuff ahead to my then- leather master with whom I was going to stay in San Francisco. Several friends along the way were expecting me to show up, at some point in between.

I met Derek one afternoon at the Coleherne. I had never felt such a stark, strong, intense, immediate attraction to any man before. We went back to Ken’s place and made love. This was much more than recreational sex; Derek felt something very similar. We agreed to get together the following day, and the following, and again and again. I had never been fucked like that before, experiencing whole-body orgasms.

We became emotionally intimate, something I had never experienced—the sexual intertwined with the emotional. I found myself falling deeply in love with him, but was slow in realizing Derek was falling in love with me too. We explored London, walking around different neighborhoods, poking into odd shops, eating in ethnic restaurants, sleeping at his place.

Eventually, the road called me; I had other promises to keep. On the day of my departure, Derek and I exchanged gifts. I gave him a book of Rumi poems, and he gave me an Indian cookbook. He saw me off at the Earls Court tube station and asked me not to unwrap his gift until I was on the plane. When I took my seat, I unwrapped his gift. Inside, Derek had written a note. “Learn to cook these dishes and I’ll be yours forever.” It wasn’t until this moment that I realized Derek loved me as much as I did him. And I realized it was now too late for me to bail on my plans to move to San Francisco. I cried, and I still cry when I think of Derek. Had I stayed in London to be with Derek, I might have made an entirely different life for myself—for both of us. This remains the only regret I still have.

![]() Les K. Wright is an author, gay activist, bear historian, and literary scholar. He is a founding member of the GLBT Historical Society San Francisco, founder of the Bear History Project, and co-author and editor of The Bear Book and The Beer Book II. He is currently working on an anthology Children of Lazarus: Voices of the “Forgotten Generation” of Long-Term AIDS Survivors. He is the publisher of Bearskin Lodge Press and lives with his cat Schuyler in Syracuse, New York.

Les K. Wright is an author, gay activist, bear historian, and literary scholar. He is a founding member of the GLBT Historical Society San Francisco, founder of the Bear History Project, and co-author and editor of The Bear Book and The Beer Book II. He is currently working on an anthology Children of Lazarus: Voices of the “Forgotten Generation” of Long-Term AIDS Survivors. He is the publisher of Bearskin Lodge Press and lives with his cat Schuyler in Syracuse, New York.

Discussion2 Comments

Really enjoyed the way you pulled me into that time period. Thank you for sharing your story.

I was touched by what you wrote too – the subject of regret is very interesting. If only Derek could read it too!