Minnie Bruce Pratt—cherished poet, teacher, and activist in the LGBTQ+ community—died on July 2. I learned about it on Facebook, and found it devastating. I owe a lot to this courageous woman. She was important to so many, and will be tremendously missed.

For two decades, Minnie Bruce shared her life and home with Leslie Feinberg, the novelist, historian, and trans activist, until Leslie died in 2014. Leslie left us Stone Butch Blues (1993), the unforgettable tale of what life was like for a transgendered person in the 1970s. In 2021, Minnie Bruce published Magnified, a haunting collection of elegiac poems “in memoriam” of Leslie. I’ve never read a more exquisitely rendered work of grief, one that so tenderly portrays a deeply loving relationship.

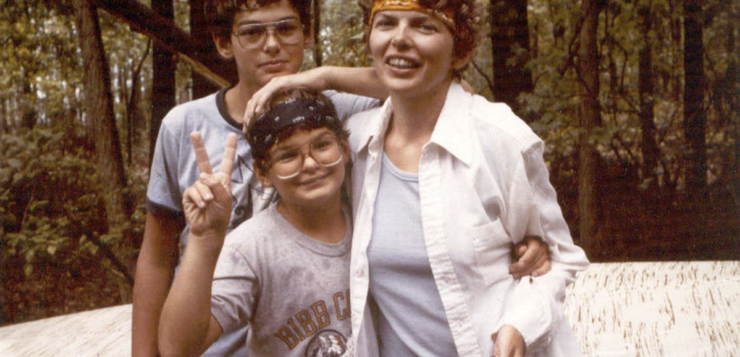

I was lucky to know Minnie Bruce when I did. In January 2021, we had a serendipitous conversation. I was working with her on Zoom, getting her slides ready for a program I was hosting for my publishing company, Headmistress Press. Until I saw her face on the screen, I had forgotten that she had published a book of poems—Crime Against Nature—about losing custody of her two young sons when she fell in love with a woman and left her then-husband to live with her.

Crime Against Nature was published in 1990, the year I turned forty, and my own son turned 21. I was living in New York City at the time, providing care to patients with HIV and immersed in AIDS activism efforts. Like so many other gay activists in the ‘90s, without ever meeting Minnie Bruce or Leslie in person, there was a kinship among us that felt like we knew them through the intimacy of their writing and the boldness of their activism.

Although I first read Crime Against Nature in the nineties, I failed to identify with it at the time. I had lost custody of my son to his father in 1975, when he was six, and although I was also a lesbian, my own pain surrounding this loss remained hidden in my psyche. Years after my loss, I was unable to connect my own experience with hers. I was barely able to acknowledge it privately, nonetheless in public.

Crime Against Nature tells a very personal story, but also offers a powerful message against patriarchy. Rather than a cautionary tale, these poems are sad but strikingly political, written as if Minnie Bruce had nothing to be ashamed of. Of course, she had no reason to be ashamed, but the title speaks volumes, identifying how shame can be thrust upon a lesbian mother and how our sexualities can be punished if (and when) we follow our desires. During our conversation in 2021, something clicked for me. I blurted out that I, too, lost custody of my young son. She listened and commiserated. There was no judgment. It was a brief exchange, and then we got on with our business. But that small moment was life-changing for me. It provided me the political and societal context in which my losing custody had occurred.

After our conversation, the crack in my own silence began to break open. Since then, I’ve gradually become more and more open to sharing my own story with others. I re-read Crime Against Nature, noting how Minnie Bruce found sustenance in acknowledging her pain and contextualizing the circumstances of her loss. She wrote about it. She was a lesbian mother who lived and wrote with all of her identities intact and visible. Women write to share, fight power, console, heal, and hopefully, to prevent pain for other women. Minnie Bruce was a mother who wrote so that other mothers might learn and find comfort in her ability to take charge of her life within her own, painful story.

Reading Minnie Bruce’s words, I felt more than solace from one lesbian mom to another. What Minnie Bruce did was proudly assert her right to love women, and in doing so, became a role model for other lesbians locked in loveless marriages with men. It takes courage to come out, loud and proud, to present to the world as the person you know yourself to be. Her words were an admonition for me to write about losing custody of my own son—easily the most traumatic thing that has ever happened to me.

My story is not unlike many women’s story of becoming noncustodial moms; the details and dates may differ, but we have some things in common: the loss, the shame, the grief. Some of us will probably never “get over” the sense that we didn’t do the job that was ours to do. In not speaking about shame, we become stuck in the private emptiness of the loss. I want to carry the message from Minnie Bruce to other lesbian mothers who have lost custody of their children that, if it is safe to do so, for them to tell their stories.

I think about the relationship between Minnie Bruce and Leslie, a love that was so deep and wide that others—those of us who never met them—could feel it. A relationship in which one another’s sum of identities was celebrated in full. By holding my shame close to my chest, I’ve denied myself the opportunity for such a relationship.

Now, in my seventies, and with the shocking loss of Minnie Bruce—who showed me the why’s and how’s of telling my own story—I feel the pressure in how little time is left for me. After our conversation, I began to open up about my own experience–I recently began writing a memoir focusing on the events surrounding losing custody of my son. I only wish that she was still here, so I could share it with her. What Minnie Bruce offered me, and others like me, was a precious gift. I am, and will continue to be, endlessly grateful for Minnie Bruce’s summoning up the courage to tell her truth.

Risa Denenberg lives on the Olympic peninsula in Washington state where she works as a nurse practitioner. She is a co-founder of Headmistress Press; curator at The Poetry Café Online; and the Reviews Editor at River Mouth Review. She has published eight collections of poetry, most recently, Rain/Dweller (MoonPath Press, 2023). She is currently working on a memoir-in-progress: Mother, Interrupted.

Risa Denenberg lives on the Olympic peninsula in Washington state where she works as a nurse practitioner. She is a co-founder of Headmistress Press; curator at The Poetry Café Online; and the Reviews Editor at River Mouth Review. She has published eight collections of poetry, most recently, Rain/Dweller (MoonPath Press, 2023). She is currently working on a memoir-in-progress: Mother, Interrupted.