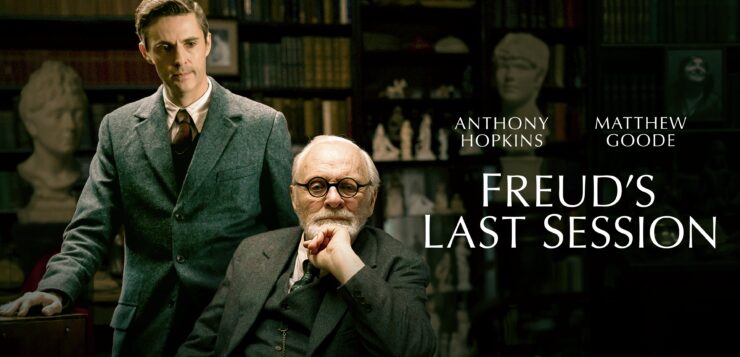

FREUD’S LAST SESSION

FREUD’S LAST SESSION

Directed by Matthew Brown

Based on a play, Freud’s Last Session (2009) by Mark St. Germain

Screenplay co-written and adapted for the screen by Matthew Brown and Mark St. Germain

Released December 22, 2023

There have been hundreds upon hundreds of books, essays, critiques, interpretations, and wild analyses of Freud’s theories. Freud’s Last Session takes up the challenge of offering the audience yet another perspective on the highly controversial psychologist.

The movie opens in England; September 3, 1939. Hitler has invaded Poland. Britain is at war with Germany. We see children being evacuated by train to the countryside. Air raids sirens pierce the air. The Blitzkrieg of England is about to begin. Freud has fled Nazi occupied Vienna and is now living in Hampstead North, London at 20 Maresfield Gardens, wherein he works from an office that has been designed to replicate the ambience of his famous room at Berggasse19 in Vienna, where he previously saw patients. The room is lined with books. His desk is covered with his collection of archeological artifacts. Freud is terminally ill with oral cancer. His is still seeing patients. His main caretaker is his daughter, Anna.

This setting provides the backdrop to the film. The main story involves the fictional meeting of Sigmund Freud (Anthony Hopkins) with the writer C.S. Lewis (Matthew Goode), future author of the Narnia series. They debate the existence of God, religion, and the meaning of life. Through flashbacks and dream sequences, we are given a window into the inner worlds of both men.

About a third into the film, the narrative shifts away from abstractions to a discussion of relationships. We learn more about Lewis’s paramour. But then, the conversation shifts again when Lewis raises the issue of homosexuality. Freud seems to show an understanding of male homosexuality, but when the subject of lesbians comes up, he finds this orientation pathological.

At this point, I found myself totally engaged with the film. For several moments, I experienced a flashback to my own training as a psychotherapist. Suddenly, I was back in the late 1970s before enlightenment had arrived at psychoanalytic institutes and lectures on homosexuality were following the traditional Freudian theoretical positions, especially for lesbians. At this lecture, the analyst was presenting ways to diagnose a hidden lesbian orientation; he emphasized the wearing of jewelry as indicative of a women’s acceptance of her traditional feminine role.

The narrative about lesbians and Freud segues into Lewis questioning Freud about his relationship to his daughter, Anna (Liv Lisa Frie). Freud evades the question, in part because of Anna’s relationship with the Tiffany heiress, Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham. (Jodi Balfour). The film intimates that they were lovers, and Freud does not accept this relationship. But this begs the question, what accounts for his greater understanding and acceptance of male same sex relationships and not lesbians?

Freud theoretically posited that a lesbian orientation was the result of something gone awry in the father/daughter relationship. By putting his own relationship with his daughter alongside his theoretical work, the film suggests that Anna’s lesbian life is related to his fathering. In fact, their relationship was so entwined that one of their colleagues in the film characterizes the bond as an example of an “attachment disorder.”

Anna was Freud’s principal caregiver throughout his illness. After his death, as the movie explains, she carried on the proverbial ‘torch’ of his theories. She lived with Tiffany Burlingham for over fifty years, yet she denied the sexual nature of their relationship. Despite what we might characterize as her ‘Boston marriage,’ Anna Freud supported conversion therapy and opposed homosexuals from becoming analysts. For complicated and complex psychological reasons, she could not separate herself from her father’s theories; he remained her proverbial North Star around whom she organized her very being and self-concept.

Freud’s Last Session is well-acted chamber work. Many interesting ideas are discussed. Like a series of analytic sessions, there are moments wherein we journey into unconscious realms.

Irene Javors is a psychotherapist and frequent contributor to GLR.

Irene Javors is a psychotherapist and frequent contributor to GLR.