AFTER A BRIEF HIATUS, here resumes my annual roundup of some of the films I saw at the Provincetown International Film Festival (PIFF) in June. While not an LGBT festival, there are always plenty of suitable entries for this magazine. Here is the final one of four.

MERCHANT IVORY

MERCHANT IVORY

Directed by Stephen Soucy

Modernist Film

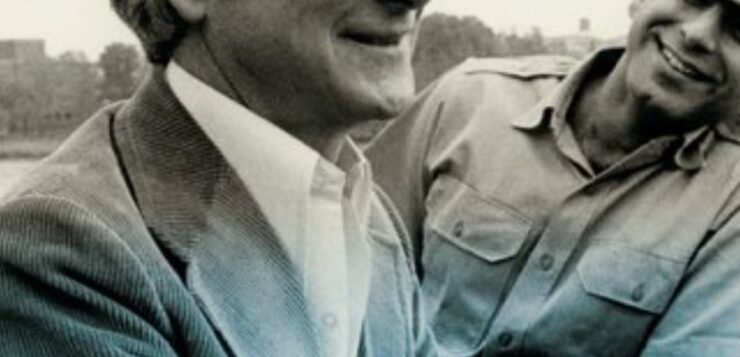

One can think of a few artistic collaborators who were also LGBT partners in real life: Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears; Merce Cunningham and John Cage; the editor and publisher of this magazine (!). But never has there been a collaboration as long-lasting or productive as that of Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, the producer and director of such great films as Howards End, A Room with a View, and The Remains of the Day, many adapted from novels by E. M. Forster and Henry James, featuring such marquee actors as Anthony Hopkins, Vanessa Redgrave, Emma Thompson, Hugh Grant, Simon Callow, and Maggie Smith. To tell their story from soup to nuts, Stephen Soucy’s new documentary, Merchant Ivory, moves at a somewhat breathtaking pace, incorporating interviews with dozens of the stars and a slew of clips from their major films.

Merchant Ivory films are known for their brilliant production values and gemlike surfaces, a level of perfection that belies the often “chaotic” scene behind the scenes. It was Ismail Merchant who both created and managed the chaos through sheer force of will and personal charisma, doing whatever was required to keep the machinery running, whether coaxing emergency funds from investors or cooking a memorable Indian repast to appease a restive cast and crew. Ivory, on the other hand, who’s still alive and was interviewed by Soucy, is described as understated and unflappable—an asset when dealing with the volatile Ismail. We learn that Ivory was the kind of director who gave his actors free rein to create their characters and enact their scenes without a lot of intervention. The secret was in the casting, for which Ivory had such a knack that he needed only to release the actors onto a set and allow the magic to happen.

While a wide range of material came in for adaptation by Ivory and writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the attraction to James and Forster is noteworthy. Both were gay men who had to tread carefully in their professional and personal lives. Recent critics have found revealing subtexts in their fiction, but it was Forster who wrote an explicitly gay novel, Maurice, which was completed in 1914 but suppressed until his death in 1970. Merchant Ivory turned it into a film starring Hugh Grant and James Wilby in 1987. Soucy stresses the boldness of this release at the height of the AIDS epidemic. It could have ruined the franchise but was so damn good that both the critics and the box office gave it two thumbs up. Forster had been determined to give Maurice a happy ending, and the film version did not deviate from this plan—a novelty for a gay film at the time.