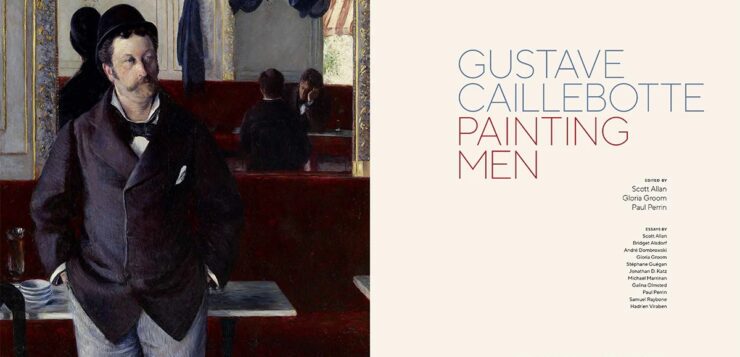

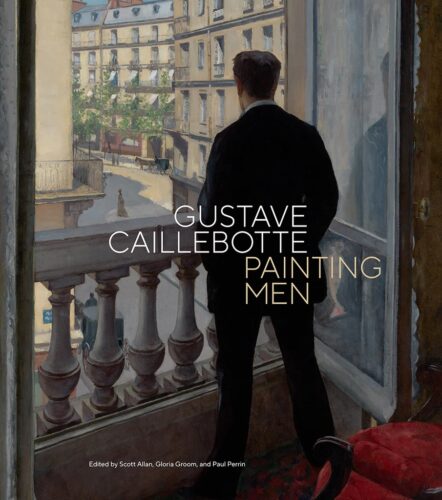

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men

At the Musée d’Orsay through January 19, 2025,

the Getty Museum February 25 – May 25, 2025, and

the Art Institute of Chicago June 29 – October 5, 2025.

Three decades after its 1995 exhibition Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, the Musée d’Orsay has co-organized another Gustave Caillebotte retrospective, in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Chicago Art Institute. In anticipation of its opening, I can only praise the comprehensive English-language catalog entitled Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men.

Caillebotte, as a member and patron of the then-reviled French Impressionists, often painted more representationally than many in the group. His early interest in photography as an art form, influences the framing and composition of his paintings, underscoring their modernity. In part because of his wealth, Caillebotte was initially criticized as being an amateur. His bequest of 68 paintings to the French government was initially refused, before they eventually became the core collection of the Musée d’Orsay. Interspersed at this exhibit are work by his contemporaries Degas, Renoir, Manet, Monet, Cassatt, Cézanne, Bazille, highlighting the similarities and the distinct differences of the Impressionists’ renderings.

The current exhibition is occasioned by the recent acquisition of two major works: Boating Party by the Musée d’Orsay and Young Man at His Window by the Getty, and also includes work loaned from nearly three dozen collections. As the catalogue explains, “This exhibition explores Caillebotte’s interest in male figures in relation to his social network and the various facets of his identity: as son, brother, friend, bachelor, soldier, yachtsman, artist, collector, patron, Parisian, and finally exurbanite in Petite Gennevilliers. … As well as promoting a new modern ideal of virile masculinity that was deeply informed by his historical circumstances, social media and gender identity, Caillebotte, in some of his most provocative works, also challenged and complicated that ideal.”

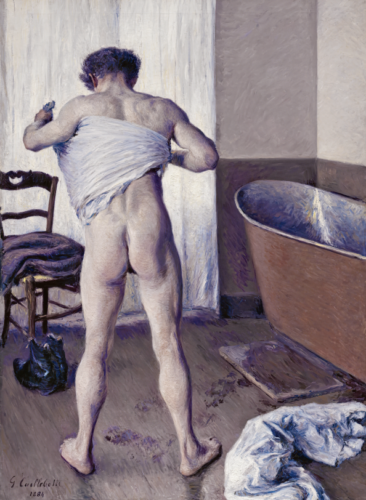

Among the ten scholarly essays, which continue to dance around the obvious homoerotic gaze of the images, of most interest to queer readers is likely the final offering: “Caillebotte, Painting Naked Men” by art professors André Dombrowski and Jonathan D. Katz. [I knew Dr. Katz during his time in San Francisco where he founded the Harvey Milk Institute, chaired S.F. City College’s Lesbian and Gay Studies Department, co-founded Queer Nation SF. and was the first artistic director of the National Queer Arts Festival.]

“This essay is therefore not about Caillebotte’s sexuality, about which we know little definitively (his heterosexuality as much as speculation as his potential homoerotic inclinations), nor is it about Caillebotte’s ‘elaboration of an invigorated modern masculinity,” as [Tamar] Garb has put it in her influential study on the painter’s nudes. “Instead, what we propose to analyze are the libidinal dynamics and the invitation to homoerotic viewing unleashed by the painting itself—a painting we understand less as a defense against homoeroticism than an open invitation to it.”

The catalogue includes full-page color plates of the 163 works in the exhibition, over a hundred of which are paintings and drawings, followed by photographs and other documentation. Tantalizingly, a potentially provocative image is missing… “In a Caillebotte family album, we find a curious carte de visite that, by all accounts, shows Caillebotte dressed in formal women’s clothing and wig, posing, as so many wealthy women of the time did, in their best and most fashionable garb for the lens of a professional photographer,” the catalogue explains. Why, one wonders, was it excluded from this comprehensive catalogue?

Intimate details about Caillebotte and his relationship to his brothers were also frequently incorporated into his work. For example, René is the Young Man at His Window and Martial is Young Man Playing Piano, both dated 1876, both set in different rooms in the family home on rue de Lisbon.

The appendices are rich with supplemental material. Appendix I offers maps of Paris and of its outskirts, highlighting locations of family, friends and sites featured in the paintings. Appendix II includes, for the first time, biographical sketches of seventeen men in Caillebotte’s social circle, and identifies the paintings in which they appear. A comprehensive list (eight and a half pages!) of references cited includes my own essay, originally published on the Queer Arts Resources website in 1998 and republished in The G&LR’s March-April 2023 issue. A comprehensive index facilitates access to the important text and images.

Rather than positing an interpretation of Caillebotte’s inner life, this handsome volume sensitively evaluates his oeuvre, thus offering a valuable contribution to the ongoing investigation of this enigmatic Impressionist. Now, even more than ever, I’m excited to see the exhibition itself when it comes to the Getty!

And now another new publication on the increasingly popular artist is available. Caillebotte: Painting is a Serious Game by Amaury Chardeau, simultaneously published by Editions Norma in French (Caillebotte : la peinture est un jeu sérieux) and English is a disappointing addition to the biographical information on the inscrutable post-Impressionist.

Commencing with the line, “We should be wary of received narratives,” and continuing (incomprehensibly) in the second chapter with, “How far do you have to wind the clock to find the right tune?” this first full-length biography of Gustave Caillebotte is as mysterious as its subject. Forcing the metaphor of games throughout, Chardeau, a Caillebotte family descendant, attempts to contextualize his relative.

from Caillebotte. Painting is a Serious Game (2025), pg. 45.

The volume also includes a wide range of adequately reproduced images of paintings and photographs, some familiar and many less so. Of particular interest is the infamous May 1868 unpublished photograph of Gustave en femme, about which Chardeau writes: “Gustave appears in drag, dressed in a crinoline shot silk skirt with trimmings and a corset buttoned up to the neck worn on a bodice his hair adorned with a wig. A pearl bracelet on the wrist and a closed fan complete the accoutrement, which gives off a baroque, waggish, or folkloric air. What can this theatrical get up and play on gender mean?” Say what?

Lamenting the lack of references to Charlotte Berthier, the mysterious woman to whom Caillebotte left a bequest: “The expurgation comes across as particularly brutal. A sister-in-law’s conservatism and the resulting omerta had a paradoxical outcome: during the 2000s, in American university circles, the theory emerged that Caillebotte was a homosexual. It is true that throughout his life, Gustave was mainly surrounded by men. Among his siblings, during his teenage years in high school, with his brothers in arms during the war of 1870, and judging by his friendships with impressionists or regatta competitors, he was a man among men. This male overrepresentation is logically translated to his output where there are four times more men than women. That being said, despite the undeniable eroticism of the spectacular Homme au bain and the play on genre [does he mean gender?]when he cross-dressed as a student, no archive seriously supports the theory of either an open or a closeted homosexuality.” The descendant doth protest too much, methinks.

Despite seemingly diligent archival research, the text is laden with supposition. The convoluted prose is perhaps a victim of translation, although no translator is indicated. Heavily footnoted, and including an index of names, this first full-length biography is flawed, but the current exhibition—and its lavish catalogue—promises a more comprehensive dive into the painter’s life and art.

Jim Van Buskirk was the program manager of the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center at the San Francisco Public Library (1992-2007).