I often say that a kiss made me gay. It happened one day when I was about forty years old. I had been married to my wife for eighteen years, and we struggled to keep the marriage intact. I spent as much time at the gym as I could, my justification for not being at home.

Roberto watched me as I dressed to go home. Every time I looked, this young stranger smiled a big smile. I packed, unpacked, and re-packed my gym bag as we continued to make eye contact. Then he nodded toward the door, and inexplicably, I followed him.

When I entered a secure bathroom, he was standing at the urinal with an erection. He said with a heavy accent, “Come to my place, Tuesday, 2:30.” I wrote down the directions, driving by his place a couple of times to make sure I had the correct address.

In one of our first meetings, he kissed me. The thought of kissing another man had never entered my head. The physical, sexual, and emotional intimacy blew my socks off. I knew at that moment that I am gay. I had never experienced sex like it before. We carried on our affair for about two years.

People ask me, “How could you not know you were gay?” I grew up in small-town rural Nebraska. Everyone looked alike, thought alike, and believed alike. If some were gay, willful ignorance kept them invisible. When I left for the University of Nebraska in 1961 and then onto its medical school, I never met anyone who was openly gay.

I was a good boy. I was an athlete, scholar, and good Lutheran. I did what was expected of me and partitioned off those parts of myself that I thought to be unacceptable.

Books in my psychiatry classes described homosexuality as a pathologic deviance. “I’m not pathological, nor deviant,” I thought, so once again I affirmed I was straight with a bit of a quirk.

I joined the navy as a flight surgeon. One of my jobs was to interview men who were caught in gay venues or were claiming to be gay to get out of the military. I had to determine if they were gay or lying about it; the conditions of their discharge depended on differentiating the two. Lying meant a dishonorable discharge and loss of any veterans’ benefits.

By age thirty-two, I had it all: a beautiful wife, two daughters, a strong career in the navy, a completed residency in psychiatry, and no college or medical school debts. By all of society’s measures, I was successful. But I was lonely. I had fit in, but fitting in wasn’t belonging.

My one-off experience with a man in New York City was disappointing and kept me in the closet for a few more years.

After Roberto’s kiss, I knew I could never put those desires to be with a man away again. I worried I would get caught sometime in a public bathroom or at an interstate rest area. This would bring greater shame to the family than if I came out, so I left my wife and, shortly after, broke it off with Roberto.

A gay fathers’ support group I visited shattered my stereotypes of what it means to be gay. These men, all with diverse backgrounds, were there because they loved their children and wanted to remain in their lives. I began to think, “Coming out for men in midlife, especially if they have children, isn’t the same as when you’re young.”

I did some research, validated my hypothesis, and wrote about it in Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight, which won a gold award for nonfiction from the Independent Book Publishers Association. Marketing a book to a hidden population who fear exposure is difficult, but I’ve heard from men all over the world that their experience parallels what I wrote about.

When I was promoting the book, one young gay man asked me, “Why would you come out at forty? You’re too old for sex.” Now toward the end of my eighth decade, I’d like to tell him I’m still not too old for sex.

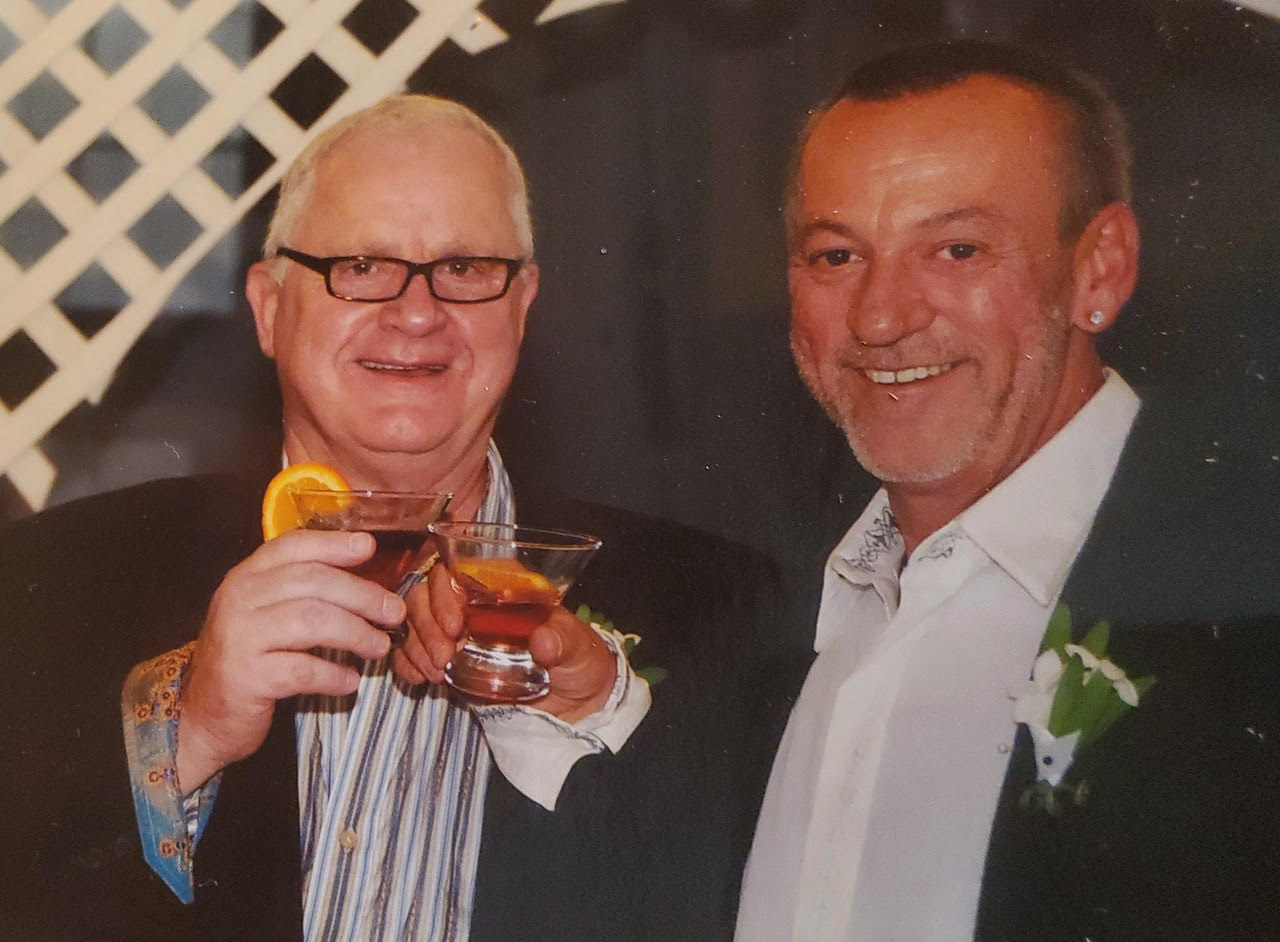

My husband, Doug, and I have been together for thirty-five years. My husband and my ex-wife, her husband, and our children and grandchildren spend holidays together. It didn’t happen easily or right away, but it happened!

I believe that we all have new opportunities. Our time is limited and diminishing, so we shouldn’t waste it. When I was sixty, I promised myself I would never sit through another boring lecture, attend parties to network with people I didn’t like, or wear a necktie.

No More Neckties: A Memoir in Essays became the title of my new book, an intensely personal look at love and heartbreak, infidelity and forgiveness, and why old men make better lovers. Many younger men know that and appreciate it; for them, age is a part of their sexual orientation.

I grew up being a good boy, and I’m sick of it. If I am known in this world at all, I want to be known as myself. I hope you approve, but it no longer matters to me if you do. I tell my stories because somewhere others feel alone, and they shouldn’t feel guilty or shameful about who they are.

Loren A. Olson, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist, a gifted storyteller, and the author of No More Neckties and Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight. He shares stories about his late-in-life coming out and the ensuing struggles he had with himself, his family, and his partner so that others feel they are not alone. His life’s mission has been to help people find ways to prevent life’s pains from becoming needless suffering.

Loren A. Olson, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist, a gifted storyteller, and the author of No More Neckties and Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight. He shares stories about his late-in-life coming out and the ensuing struggles he had with himself, his family, and his partner so that others feel they are not alone. His life’s mission has been to help people find ways to prevent life’s pains from becoming needless suffering.

Discussion1 Comment

A great article. I love to read this; it’s so blunt, but honest,