THE TALE of Puccini’s final opera is well known: the icy princess Turandot refuses to give up her body or her heart to any man, conferring a death sentence on all who attempt to win her hand in marriage by answering three riddles, until she is transfigured by the fires of love. Okay, so it was written in the 12th century by Persian poet Nizami, so I guess that’s what you can expect.

Apart from a few pleasing melodies, Turandot is far from Puccini’s most enjoyable work, with its insistent attempts at depicting “orientalism” for Western ears. Audiences have come to expect lush sets and lavish costumes in line with the opera’s extravagant “exoticism.” Not so at the Canadian Opera Company this year, thankfully. Nor are there any divas or divos, great or small. In this production, each part serves the whole in a welcome reinvention that subverts traditional operatic hierarchies.

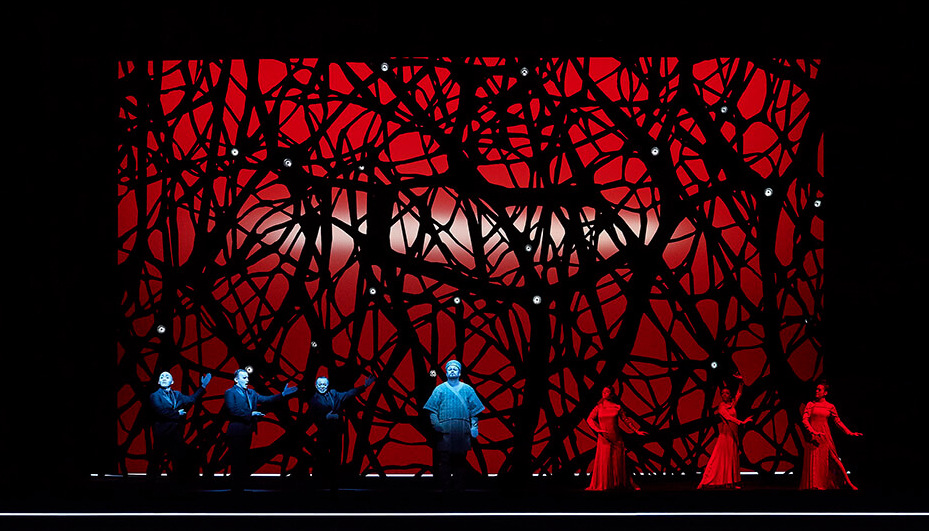

Robert Wilson’s Turandot is a true marriage of the auditory and the visual. It does not merely frame the action but contains and transfigures it, giving back the singers and the costumes and their carefully executed stage gestures in a way that delivers far more than the sum of its parts.

The production is not lacking in tradition by any means. There is Kabuki and there is Noh, and there is a geometrical beauty of the sort that made Wilson’s staging the early works of composer Philip Glass so transcendent even while the critics were crying foul. (Guess who had the last word in that debate?) Some may be tempted to dismiss this production as “minimalist,” but perhaps without a full understanding of this term. Minimalism is not simply the reduction of a work to a bare minimum; at its best it is an attempt at making the most from the least.

In this case, there is an extraordinary richness in the blending of the basic elements of music, costume, lighting, and a stage blocking so precise as to create stunning visual tableaux that reflect the opera both psychologically and dramatically. The dominant colors throughout most of the opera are cool, even cold, in keeping with Turandot’s icy demeanor. The only hot color is Turandot herself, dressed in the brilliant reds of blood or anger. Only toward the end, as her heart melts, does warmth suffuse the stage, ultimately transformed by love.

All of this is in line with Wilson’s professed aesthetic that “light is the most important actor on stage.” From start to finish, the entire production is an ever-evolving feast for eyes and ears, if you don’t let your expectations, or tradition, stand in the way.

Opera has a long history that can be a dead weight. At best, these traditions are pleasing to the eye and the ear. At worst, they are stultifying and dull. If you want the old and dead, as they say, go to a museum or a cemetery. If you want the new and alive, then hire a visionary. Robert Wilson is such a visionary, and his vision is a gift. We would expect nothing less from the man who gave us Einstein on the Beach all those years ago. I am glad to see that he hasn’t lost his fire.

Robert Wilson’s Turandot ran at the Canadian Opera Company, Sept. 27 – Oct. 28, 2019.

Jeffrey Round is an author, director, and song writer whose latest novel is titled Shadow Puppet, a fictionalization of the serial killings in Toronto’s gay community from 2010 to 2017.