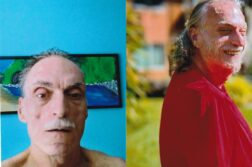

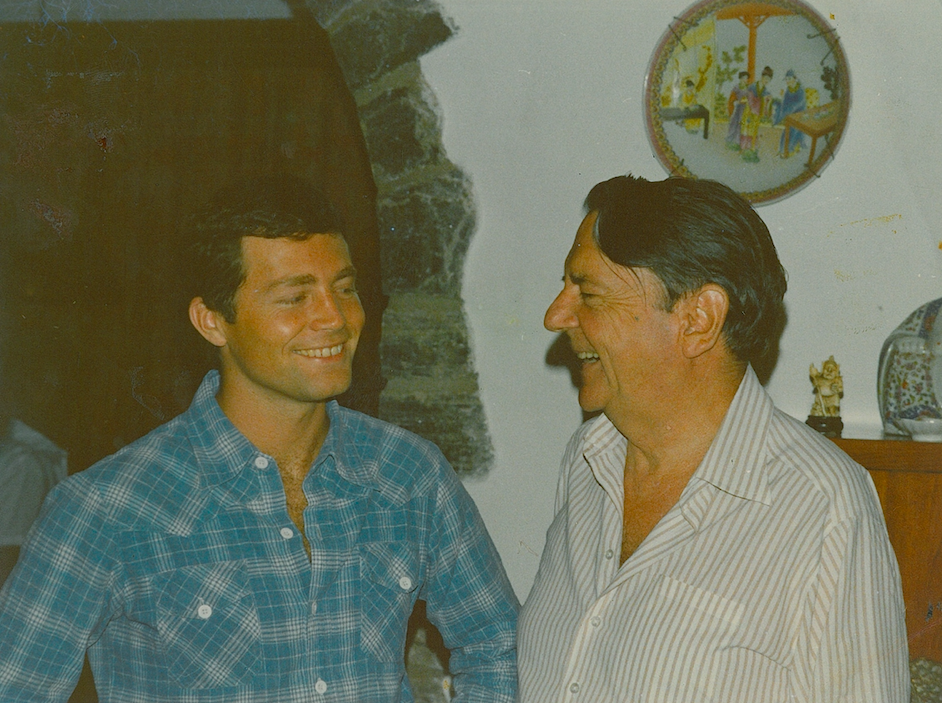

HOW DID I COME to meet the writer Robin Maugham—the man who was to be my first openly gay relationship? Socially, we were poles apart. For starters, the age gap between us was bigger than the Grand Canyon. I was nearly twenty and Robin was in his mid-fifties. I’d been brought up in the East End, a hundred yards from the smoky silt of the Thames. I was the product of the local public school; Robin was the product of the freshly mowed playing fields of Eton.

Robin’s father had been a Lord Chancellor of England; his uncle, Somerset Maugham. It’s not an exaggeration to say that in his day he knew every big gun and ne’er-do-well of the era, from the political giants to the criminal intriguers. And along the way he still found time to write a couple of classic books: The Servant and The Wrong People, both still in print; the latter about to be made into a major film.

When I grew up in the 1950s, being “queer” sent more shivers down your spine than Count Dracula’s bloodstained fangs. My father was one of the “Shoulders back, chin in!” brigade. My main place of refuge from his nightly rants was in our local library, living out a secret life with my head full of books—mainly about the daring campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte, of all people. In fact, I got fixated on the strict disciplinarian who liked a bit of stick and ended up with his ass covered in ermine fur. You could say he was a foreshadowing of my attraction for men of power.

As a youngster I’d always taken a keen interest in field events, and I’d noticed that Mr. Hartfield, the teacher in charge of extracurricular activities, was always at the finishing line to cheer me on “Come on Lawrence, you can do it man!”

Mr. Hartfield was Welsh, and one of the new breed brought in during the ’60s—part of the loose-collar set. Most of the other masters were stoic WWI veterans. Mr. Hartfield was free-thinking, and in my teenage eyes, he had a look of rebellion that reminded me of Malcolm McDowell’s character in the movie, If. The other blokes in my form said he was as bent as a docker’s hook. But then, you only had to wear the wrong trainers in our school and you were considered a weirdo. So I took no notice. Even when he popped his head into the changing hut, I didn’t think there was anything odd about the way he stared at me. In fact, I liked it.

Next was Harry Waites. I met Harry in the Russian baths in Poplar. By the mid-’60s, the steam rooms had turned into an oasis for market people, boxers, councilors—including gentlemen of land and rank who preferred to take a break from planting rare trees and go plant their hands instead on some of the more common saplings of the hot sweaty variety.

I met Harry in the Dry Room—a sort of neutral zone where grand elderly gentlemen were allowed to oil the grime off a straight bloke’s six pack. Harry gave my knee a nudge. When I turned to take a look, a handsome dark eyed man of about twenty stared straight back at me—and that was it.

Harry was the first man to kiss me. He also introduced me to the next link.

Peter was an art teacher. When my father threw me out on the street for wearing frilly shirts, he came to my rescue. He lived in an attic flat that was pure chaos—a real homage to anarchy. Dominating his bedsit was a grand piano. I recall there was a half-eaten cheese sandwich resting on the music stand. Peter opened my eyes to high culture. Copies of old masters were in every corner; LPs of the great composers surrounded a black box record player. That night he gave me my own mattress to sleep on.

Peter knew my dream was to continue studying, so within a few days I was being interviewed by the headmaster of the college where he taught. That same afternoon I was offered a place at his high school. The thing was, for all the man’s passion for self-expression, the only symphony Peter played with those talented fingers of his, was on his keyboard – he was just plain honorable.

It was Peter who introduced me to the film director Brian Desmond Hurst.

Brian was known in the movie industry for his classic film Scrooge, starring Alastair Sim. However, he was he was also known in Belgravia for pausing at one of the many building sites and gripping hold of a scaffolding pole and declaring to some muscular Adonis, in a tone that would have put Donald Wolfit to shame: “Would you kindly help an old man home?!” Adding later: “There’s a part for you as an angel in me forthcoming epic.” The film mogul believed he was in direct contact with the Almighty; so, nothing unusual there. And as it panned out there was certainly a part for me—because it was Brian who took my hand, at a lunch party, and place it into the hand of my partner to be, Robin Maugham – with the memorable words: “God has brought you together!”

I lived and worked with Robin for over ten years and on occasions, during his crazy bouts of drunkenness, ran from him howling into the night. But within that amazing period he had dictated a shelf of novels, plays and films to me and somehow at the end of all the mayhem we were still in bloody love; it was a love that lasted the duration of the writer’s life—and what a life it was.

My last words to my partner were: “Amor Vincit Omnia.” So, even if he isn’t with us, I’m making sure the world will remember him. I’m working on a book based on my search for his missing diaries.

Love conquers everything, mate.

William Lawrence is a playwright, writer, sculptor and former assistant of Robin Maugham. His critically acclaimed plays include Never Walk Alone and Tomorrow Belongs to Nobody. He lives in St. Leonards-On-Sea, England.