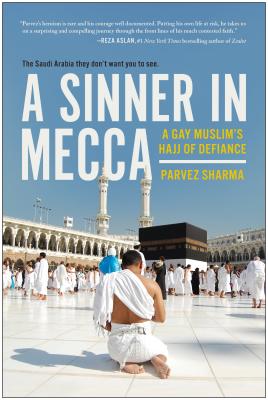

A Sinner in Mecca: A Gay Muslim’s Hajj of Defiance

A Sinner in Mecca: A Gay Muslim’s Hajj of Defiance

by Parvez Sharma

BenBella Books. 280 pages, $16.95

IN THIS POWERFUL MEMOIR, filmmaker Parvez Sharma describes the physical, emotional, and spiritual journey he embarked on while going on the Hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca. The risks were great indeed, for as an openly gay Muslim and director of A Jihad for Love, Sharma faced serious consequences if he were recognized. Furthermore, he planned to covertly film the pilgrimage on his iPhone, which became the basis for the film A Sinner in Mecca. This was also dangerous, for the Saudis take pains to make sure that all films about the Hajj are favorable. This book is a companion piece of sorts to the film, but stands on its own.

Before making the pilgrimage, Sharma poignantly recalls his awakening sexuality some years earlier. Born and raised in India, his first sexual experience was with Muhammad, the caretaker of one of his favorite shrines, who taught Sharma how to pray “properly” in exchange for English lessons. He writes that “there was nothing I wanted more than to take off his white trousers.” He also remembers the desire he felt toward cricket players, particularly admiring the Pakistani team for “their taller, and in my eyes more masculine, physiques.”

He recalls his distant aunt Khala, who would paint a verbal description of the Prophet Muhammad so beautiful that the young Sharma would feel “a forbidden longing I could not explain.” Because of the religious prohibition against homosexuality, Sharma grew up feeling shame about his desires. This was not helped by his mother’s severe disapproval. She later died from cancer while he was away exploring his sexuality, and for years he felt as though he had killed her.

Before he could travel to Mecca, he had to make arrangements. Because of a childhood medical issue, he was never circumcised. Sharma feared that his fellow pilgrims would discover his “un-Muslim penis” due to the required outfit for the Hajj, two seamless pieces of white cloth called an ihram. So he had an operation. He also removed many photos from his iPhone, keeping one of his husband.

In the book, Sharma captures the grueling ordeals of many of the rituals involved in the pilgrimage, which are only intensified by the immense crowds, the seeming indifference to the safety of the pilgrims, and the religious police’s brutal interpretation of religious practice. At one point, he writes, “I emerged … exhausted, bruised, calloused, dehydrated, and spiritually broken.” Despite these experiences, he makes peace with his mother’s death and feels he can call himself Muslim.

Sharma has sharp criticisms for both Saudi Arabia and Wahhabism. A strict puritanical form of the religion, the latter has become popular throughout the world through the Saudis’ funding of religious schools. He argues that ISIS, which he calls Daesh, draws much of its ideology from Wahhabism, particularly its treatment of homosexuals and women and its glorification of violence.

Despite the heavy subject matter, the book has a sense of humor. For example, some of his friends point out that when pronounced differently, Daesh might be translated as “stick it in.” The book is full of information about the history of Islam and the Muslim world. Sharma also includes a helpful glossary of terms. There is some repetition, but many non-Muslim readers might benefit from it. This is a well-done book that offers a valuable perspective in these fraught times.

________________________________________________________

Charles Green, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.