Published in: July-August 2016 issue.

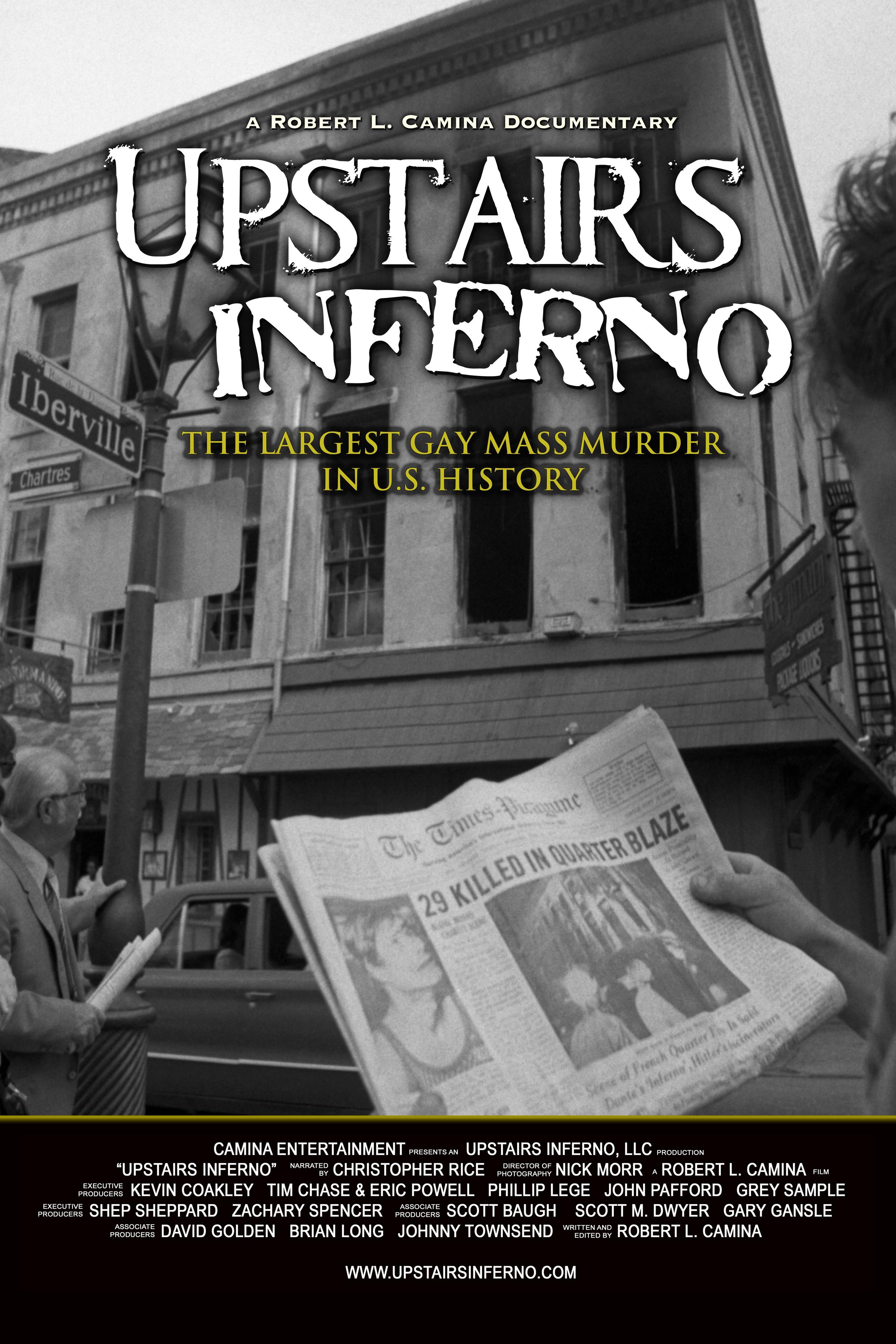

Upstairs Inferno

Upstairs Inferno

Directed by Robert Camina

Camina Entertainment

THE DEADLIEST CRIME against GLBT people in U.S. history occurred on June 24, 1973, at a gay bar in New Orleans. On that night, an arsonist set fire to the bar and consequently killed 32 people. Now if you’ve never heard of the Up Stairs Lounge arson, you’re not alone. Until a few years ago very few people, including in New Orleans, had heard of the tragedy.