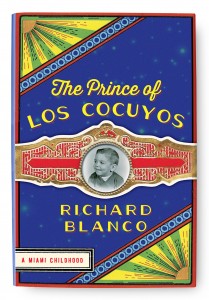

The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood

The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood

by Richard Blanco

HarperCollins. 272 pages, $25.99

RICHARD BLANCO was catapulted into fame on January 21st, 2013, when he recited his poem “One Today” at President Oba-ma’s second inauguration ceremony. As an openly gay Cuban-American poet, Blanco was at once a revolutionary choice for the occasion and a bold statement by Obama about his own vision for America. In his new memoir, The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood, Blanco tries his hand at a second memoir, a kind of prequel to 2013’s For All of Us, One Today: An Inaugural Poet’s Journey, and the end result is as mesmerizing as the flight of lightning bugs (cocuyos) illuminating a sultry summer night sky in South Florida.

Blanco’s childhood souvenirs are distilled into seven distinct vignettes set in the changing Miami landscape of the mid-1970s and early ’80s. The opening chapter sets the tone for the rest of the book by recounting the very first American San Giving (Thanksgiving) thrown by his very Cuban family at his insistence: “My teacher seemed to understand Thanksgiving like a true American, even though she was Cuban also. Maybe, I thought, if I convince Abuela [Grandma] to have a real Thanksgiving, she and the whole family will finally understand too” [italics in the original]. The feast included the traditional turkey with instant Stove Top stuffing and pumpkin pie alongside Cuban staples such as frijoles negros (black beans) and roasted pork. Indeed, young Ricky straddles two cultures: the world left behind by his parents due to Castro’s revolution and the promises of free America embodied in such icons as The Brady Bunch, New Wave music, and junk food.

Blanco portrays several unforgettable characters, including Yetta, the quintessential Miami Beach Jewish retiree in the pre-South Beach glitz, and the hunky Ariel, who almost drowned as he came over to the U.S. during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift. Several events mark the journey The nascent gay identity takes center stage as the memoir delves into adolescence, and Blanco confronts his first real crushes on other males. At El Cocuyito, the convenience store owned by one of his relatives and where he has a summer job, Ricardo meets Victor, a co-worker. After an extraneous task, they both take their sweat-soaked shirts off, only to eye each other: “The sweat dripping down his hairy chest and his muscular back excited me the same way Francisco Hernandez’s body had excited me in the locker room at school.” They proceed to dry each other off with Victor’s red bandana: “My body tingled—nothing like when I had kissed Anita. I knew without knowing.” The memoir deals with sexuality obliquely without trivializing it, thus replicating the ambivalence felt by Ricardo’s adolescent persona, translated in a coy but authentic tone. Despite its comedic aspects, the memoir is ultimately tinged with nostalgia. The Cuban family yearns to go back “home,” but the longer they’re away, the more elusive that particular goal becomes. Ricky has the same feeling of homelessness and hybridity, exacerbated by his sexual awakening. Toward the end of the memoir, he asks: “Who was Ricardo Blanco? Would I be an architect? Would I be a husband and father, or would I grow up to love men as Abuela feared? I dove into the ocean, swam eyes-open underwater, fast and hard until I had to come up for air. Heart thumping, I floated on my back and stared straight up at the clouds as they changed their shapes, continuously becoming something new.” In his inaugural poem, Blanco paradoxically highlighted the unity of our country through its collective difference, the American experience lived under one sky and over our ground. Similarly, the memoir has a universal appeal because of its emphasis on queerness: Blanco’s straddling of cultures and gender categories makes him the most American of poets. That said, he has captured with great accuracy a certain Cuban-American exiled gestalt that’s reminiscent of the popular TV show of the late 70s, ¿Qué Pasa, USA? For us gay Cuban-Americans, Blanco’s words represent a much needed voice, a guiding cocuyo illuminating our futures by mapping new constellations of hope alluded to in his poem “One Today.” ¡Gracias, Ricardo! of Blanco into awareness of both racism and homophobia. During his first trip to Disney World, recounted in the chapter entitled “El Ratoncito Miguel,” an American clerk at a service plaza shows contempt for Papá, Ricky’s father, as he doesn’t understand his broken English: “Listen, mistah, I can’t understand one iota of what you be saying. You people need to get learning English. You’re in America.” At the same time, the matriarchal Abuela chides any slight deviation by Ricky from the codes of Cuban masculinity. When he brings home a rug kit, Abuela confiscates it, stating: “A rug? Con yarn? What’s next—ballet? I told you diez mil veces: it’s better to be it and not to look like it, than to look like it even if you are not it.” Blanco painfully reflects that “At that age, I only understood that it meant watching telenovelas; it was my paint-by-number sets; it was my cousin’s Easy-Bake Oven I wanted for my own—all the things I enjoyed for which she constantly humiliated me.”

of Blanco into awareness of both racism and homophobia. During his first trip to Disney World, recounted in the chapter entitled “El Ratoncito Miguel,” an American clerk at a service plaza shows contempt for Papá, Ricky’s father, as he doesn’t understand his broken English: “Listen, mistah, I can’t understand one iota of what you be saying. You people need to get learning English. You’re in America.” At the same time, the matriarchal Abuela chides any slight deviation by Ricky from the codes of Cuban masculinity. When he brings home a rug kit, Abuela confiscates it, stating: “A rug? Con yarn? What’s next—ballet? I told you diez mil veces: it’s better to be it and not to look like it, than to look like it even if you are not it.” Blanco painfully reflects that “At that age, I only understood that it meant watching telenovelas; it was my paint-by-number sets; it was my cousin’s Easy-Bake Oven I wanted for my own—all the things I enjoyed for which she constantly humiliated me.”

Eduardo Febles is an assistant professor in the Modern Languages Dept. of Simmons College.