CHRISTINA SCHLESINGER is a wickedly interesting, unapologetic, and high-spirited visual artist whose erotic works were featured in a “pop-up” exhibition at the Leslie Lohman Museum in New York’s Soho district in late January.

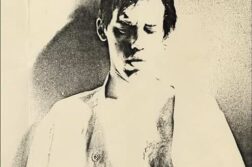

The show was called Tomboys, and it featured 36 paintings of butch females by the artist, many of them self-portraits painted onto T-shirts and other articles of clothing. In self-portraits based on old photographs of herself, Schlesinger tomboyishly mugs for the camera. Her portrayals collapse time and space like the pages from a lesbian version of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, detailing the sweetness of lost time and memory. Yet the artist’s images are not just about her own memories but speak with wit and compassion to every tomboy who has felt same-sex desire and loved another girl.

Schlesinger came of age in the 1970s, at the dawn of the gay liberation era but a time when gay men and lesbians were still reviled and ostracized and known only by names like homo, sissy, faggot, bull dyke, lesbo, and queer. Even as late as the 1990s, the idea that a lesbian artist would dare to depict her authentic sexual self, much less display same-sex eroticism in a public context, was unthinkable. It was against this backdrop that Schlesinger began to create images depicting her own coming of age and the various sexual practices and pleasures of women loving women.

But finding an outlet for her work would prove another matter. Boyish girls with stiff dildos on their hands and knees adoring their girlfriends were the stuff of future lesbian wet dreams. In the 1990s, images of lesbian sexual desire did not figure prominently in the mainstream, or even the underground, art world. Only in 2015, and only because the Leslie-Lohman Museum made it happen, was this aspect of Schlesinger’s pioneering work shown to the general public. When this work was first created—even though she was well-known for her landscapes and other paintings, and even though heterosexual (and even gay male) art was experiencing a new period of sexual freedom—she couldn’t find a venue for it. The idea of parting and penetrating another women with a dildo, something that’s taken for granted today among lesbians, was taboo.

As an out lesbian, Schlesinger put herself in a dangerous position by being overtly joyous about lesbian sex and declaring herself to be the subject of her art. She wasn’t out to shock anyone but was only rendering her lesbian desire and illustrating the erotic pleasure she derived from making love to women. Her intimate drawings depicting, say, a woman using a dildo to part the folds of a lover’s vagina, were considered outragous at the time. This kind of imagery is repeated in slightly differing variations throughout the series, showing lesbian erotic desire as simply a part of nature.

It is gratifying to me as an art critic and a lesbian to think that after 22 years of gathering dust in her studio, these works can finally be exhibited—all because a curator named Cupid Ojala believed that Schlesinger’s work would make a new generation aware of how far we have come. My only regret is that these pop-up shows are so short-lived, so her work was on display for far too short a time. However, a good introduction to her work can be found on her website (www.christinaschlesinger.com).

I communicated with Christina on-line in late December about her forthcoming show.