Editor’s Note: Edward Albee died on Friday, September 16th, 2016, at the age of 88. He passed away at his summer home in Montauk, New York, after a short illness. He was one of the most important and iconic American playwrights of the 20th century. He wrote some of the most memorable plays in the modern repertory, such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which must have been performed on most of the world’s stages, and there cannot have been many actors who haven’t coveted one of his roles, whether in The Zoo Story, Three Tall Women, A Delicate Balance, or other more recent work like The Goat, Or Who Is Sylvia? (2002). He won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama three times and received numerous other honors and awards, such as the National Medal of Arts.

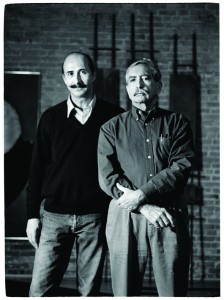

The author of this piece, Dimitris Yeros, is a Greek painter and photographer who was a friend of Albee’s for the last fifteen years of the playwright’s life. Albee wrote the preface for Yeros’ 2011 book Shades of Love. Here Yeros writes about the last time he met the playwright in his Manhattan home.

I HAD SEEN HIM again in the spring of 2010. It was another dull, rainy New York afternoon. That time, we had sat for quite a while in his large, stylish home, whose walls were filled with modern art, including a Chagall, a Kandinsky, a Lipchitz, and two Arps, while several dozen African wooden sculptures stood on the floor and watched us with expressionless eyes. There was also a beautiful white-and-beige-colored cat walking around nonchalantly, flirtatiously rubbing against our legs.

Over the years of our friendship, I had photographed him on a few occasions, and he had used some of my photographs for the covers of books and theater programs.

I photographed him for the last time that day. As always, he was smartly dressed and wore elegant, expensive socks. Afterwards, he took me to a small Chinese restaurant two blocks away from his home, which he appeared to frequent. He ate a few pieces of sushi and I a strange eel that may or may not have been a snake. He also drank a cup of tea, which he had replaced twice because it was too weak, and he complained to the waitress about the volume of the music. Although he was somewhat haggard and bent, his pace was quick and lively in the rain. His spirit and his attitude to life, the theater, and sex had not changed at all over the years.

We had a long discussion about our work, the visual arts, which he loved, the theater, the sorry state of Broadway, the musicals he wasn’t keen on, democracy as virtual reality, Greece’s burgeoning financial problems, the models in my photographs, and so on. Once more, he reiterated how much he wanted to revisit my country. When the bill came and I asked to pay, he told me, looking at me side-on in a manner that brooked no objection: “This is Tribeca, this is New York, and you’re a guest. You’re not paying!”

A few months later, his memory began to weaken and his heart started to cause him such severe problems that he decided to have an operation. The doctors told him that he would gain at least an extra decade by having it. The operation lasted roughly six hours, and it is assumed that his memory and physical strength worsened as a result of the anesthesia. He began not recognizing those close to him and was unaware of his surroundings most of the time. On occasion, he did not even recognize Jakob Holder, also a playwright, who had been his assistant for fourteen years. Nevertheless, he knew that he was Edward Albee, and when I sent him fifty copies of a poem he had written, which was to be circulated in a collectors’ edition together with my photographs, he gladly signed them one by one in large, fine letters. Jakob had written to tell me that Albee had stopped and read the poem as he signed, and he said he liked it. And added: “I wrote this for Dimitris.”

In the years that followed, I continued to mail him my good wishes on holidays and birthdays, along with various photographs he had asked me to send him from the very start of our acquaintance, because he would like to have them in his collection. However, when I didn’t receive a personal reply for a long time, I emailed Jakob, whose answer described the poor condition Albee was in—of which I had been totally unaware—and told me it was pointless my sending him anything under the circumstances.

I saw Edward again at midday on November 12th, 2015, again at his home. I didn’t care whether he recognized his friends or not; I wanted to see him. He was a person who had been generous with his friendship, loved and supported my work. Jakob had told me that the great playwright was most likely to be feeling his best between noon and one p.m. Before and after that time, it was doubtful that I would catch him awake. He told me that Edward had been in the hospital the previous month, almost in a coma, and that his condition was extremely worrying. Suddenly, however, out of the blue, he had perked up and begun to speak again. Jakob told me how fortunate I was that he would be awake when we met.

He led me to the spacious kitchen where Albee was sitting in a large, black armchair of the type that converts into a bed, I think. Because of how they had described him to me, and perhaps due to my own fertile imagination, if not naïveté, I had expected to see the shriveled-up figure of an 87-year-old man who was spending his last days on earth. Instead, I saw a man far handsomer than he had been at our last meeting. His face looked fresh, his white hair was shorter than ever, clean, and well-combed, and his slender fingers with their intense blue veins seemed transparent. He had replaced his old hearing aid with a new one, more modern and discreet. His legs were covered with a warm, blue blanket. On the wall above and behind his head hung two small paintings, and on the table, to his right, there were an oversized African wooden head, an unusually large digital clock, and two small bottles of water. A young African-American woman, one of the four-person team who looked after him in six-hour shifts 24 hours a day, was at the sink discreetly washing the dishes. She didn’t appear to pay any attention to my presence.

As soon as Edward saw me, his eyes brightened. He smiled heartily and gave me his hand as if he had been waiting for me a long time. I was taken aback by this unexpected reaction and did not know how to behave. Suddenly, I found myself face-to-face with someone who appeared to be in possession of all his faculties, who seemed to recognize me and to be pleased that I was visiting him. Trying to get over the surprise, I paid him various compliments, many of them sincere, and he reciprocated in kind as nearly everyone does when they find themselves temporarily enmeshed in formalities. As I was still stunned by the embarrassment my friend’s normality had caused me, and as I was looking into his eyes striving to interpret the unexpected reality, he asked me, “What are you planning? What have you got coming up?”—and that was the coup de grâce. They had told me he didn’t remember a thing and that everything was pretend, and here he was giving the impression that he knew full well whom he was speaking to, and asking me about my work. I replied that they would be presenting a book of mine in New York in a couple of days and that I was sorry he couldn’t come. He told me peremptorily, just as he used to do in the good old days: “I’ll come.” I replied that it would be difficult for him to come, and he dug his heels in, as he was wont to do: “I must come.” I looked at him questioningly, wondering again if all of this—so like an incident from one of his plays—was really happening, and if he meant what he was saying. “I must come,” he said to me again.

The woman who was washing the dishes spoke for the first and last time: “Edward, you can’t go. I’m taking you to the doctor on that day.” Going back to his question, I told him I was planning to publish our book, Another Narcissus, as soon as I returned to Greece. A few years ago, Edward had written a poem about one of my photographs that depicted a boy, as fine-looking as Narcissus, with five snails crawling over his bare chest. The beautiful poem had inspired me to take a few more photographs, which is when we’d talked about bringing out a small book with the poem and photographs—not to market, but solely for our friends.

My announcement elicited no reaction from him. He did not remember anything about it and looked at me questioningly, waiting for me to jog his memory in some way. I had a full-sized mockup of the book with me and gave it to him. He started to flip through the pages, looking at the photographs one by one and showing great interest. “Do you remember when we met and you asked me jokingly when I’d photograph you with snails on your chest?,” I said to him, and I showed him the photograph I’d described. He did not remember, but laughed at the description of our first meeting. I had sent him several of the book’s photographs long ago, when he was still well, and he had told me he liked them and that the model was very handsome and ideal for his poem. “I’m honored,” he said to me, and I, holding his hand, told him the honor was mine and that I would never forget the kindness that he had shown me through all the years of our friendship.

As we were talking, he began to turn the pages of the mockup again with the same interest and attention. “Is it the same boy in all the photographs?,” he asked me. Yes, I answered, it was the same boy. When, close to the end of the book, he reached the page with a photograph of the two of us together, he lingered over it. “It’s been thirteen years since then,” I said to him, “and you look much better now.” Indeed, being armchair-bound with his strength abandoning him had made him calm and tender, and this was reflected on his face, which was more likeable and handsome than before. This man, who a few short years ago had been so full of anger and flared up at the slightest provocation, had now been transformed into an angel! But his interest in the book seemed inexhaustible, and he resumed his leafing. When he asked me again, “Is it the same boy?,” I realized as he reached the end of the short book that he had already forgotten its beginning.

Because I knew from Louise Bourgeois that old people like sweets, while their caretakers never offer them any, I had brought a selection of pastries with me. I asked if he wanted me to bring him one of the pastries and he replied indifferently: “No.” Because I suspected that he might not have heard me, I asked him again: “But, don’t you like chocolates?” “Oh, I like chocolates very much,” he said. So I went out of the kitchen and sought out Jakob to ask him to give Edward one. But he told me that Edward should not eat sweets because he has diabetes and that, when I got back to the kitchen, he would have forgotten all about it. I asked him suspiciously if it was certain the writer would not remember anything, and he answered with absolute certainty: “Unfortunately, Dimitris, that is the way it is. He does not remember anything and pretends to remember.” Indeed, when I returned to him, he did not ask about the pastry that I had promised. I asked him if I had made him tired and if I should leave. “I’m always tired,” he told me in a low voice. “Then I should go,” I continued. “No, stay, you don’t tire me; the years have tired me,” he said with despair.

Because I was afraid that my presence was keeping Jakob away from his work, I said to Edward: “Should I go and show the book to Jakob, too?” “Certainly,” he replied. After I had shown the book to his assistant, I returned to the kitchen to say goodbye and leave. However, in the meantime, he had tilted his head forward and fallen asleep; it was his bedtime. I got my coat, bid the woman who was still at the sink goodbye with a nod, and left quietly without waking him. Before I left the apartment, though, I turned around and looked back at him one more time through the open kitchen door, quite certain I would never see him again.

Dimitris Yeros is a painter and photographer based in Athens. His latest book is Photographing Gabriel Garcia Márquez (Kerber).