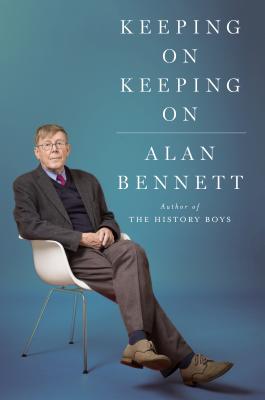

SINCE THE EARLY 1970s, the British writer Alan Bennett has kept “a sporadic diary,” extracts from which have been annually published in the London Review of Books. The diaries are yet another winner among the many books, plays, and screenplays that the enormously talented Bennett—whose works include The History Boys, The Madness of George III,and The Habit of Art—has turned out during his fifty-year (and still going) career.

Over the years, these diary entries have found their way into three volumes of Bennett’s collected prose. The American edition of the third volume came out last year. This installment (diaries from 2005-2015), written when Bennett was in his seventies, finds him “beginning to tidy up a bit.” In addition to his reflections, the tidying up includes several occasional pieces: introductions to his plays, program notes, memorial minutes, prefaces to exhibitions, and a sermon preached at King’s College Chapel. The latter he calls “a hazard”: “One isn’t supposed to preach and gets told off if one does.” The book—all 700-plus pages of it—is rounded off with the complete texts of two plays that were “put away in a drawer” and never staged.

But it’s the diaries that are the real delight of this volume. Bennett once said that his diaries comprise bits of conversation with himself. What a pleasure to eavesdrop on these conversations, which are full of mordant wit, verbal panache, and straight-up honesty. And while this installment of the diaries is more candid about his gay life (“nowadays no one seems to mind”), for this reader the real interest lies in the activities and thoughts of a particularly intelligent, observant, witty, and principled man of letters, one who just happens to be gay.

In the course of the decade, Bennett wins a Tony for Best Play, enters into a civil partnership with his long-term companion Rupert Thomas, and donates his papers to Oxford’s Bodleian Library. “Lest it should be thought there had been any sort of competition, this is the only enquiry I’ve ever had,” he notes. “One offer in forty years makes me some sort of bibliographical wallflower.” Sadly, this is also the decade of terrorist bombings on the Tube, police misconduct, riots, and increased drug addiction, all of which Bennett comments on.

The diaries chronicle numerous outings and excursions: to art galleries and museums, antique stores and architectural salvage shops, gardens and doctors’ offices, funerals and memorial services. He and Rupert are especially keen on poking around historically important churches, so much so that on one occasion they break into the gated ruins of a medieval abbey: “an illicit delight.” There are lunches to attend, interviews to give, radio programs to participate in, alterations to their house to supervise, opening nights to appear at. In short, his life is “a bit of a fullock … one thing piled on another.” Happily—wonderfully, really—all of these activities, the quotidian as well as the festive, are engagingly narrated. What a captivating dinner companion Bennett must be!

Bennett’s alertness and powers of description—about everything from hens (“fastidious in their footwork”) to waiters in Rome (“looking like dentists or professors of philosophy”)—are magnificently trenchant. Looking at Van Gogh, he’s in awe of how quickly and recklessly the artist painted, so much so that “any sense of painterly self-preservation is abandoned in the fever of getting it down.” And then he adds, “This has a message for me at this late stage in my life.”

Frequently mentioned in the diaries is his reading life. We never find Bennett without “a book on the go.” Reading The Secret Life of Cows(2017), by Rosamund Young, he wonders that the author “never mentions any idiosyncrasies when the cows go with the bull.” This reticence, he surmises, may be “a measure of her respect for her charges, feeling that cows are entitled to their privacy as much as their keepers.” This pitch-perfect admixture of wit, intelligence, and good common sense has been a hallmark of Bennett’s writing throughout his distinguished career.

Especially delicious is the way Bennett rails against the mediocrity, dishonesty, and tastelessness of so much of modern British life. He execrates the “wholesale destruction of Victorian buildings” and the conversion of decent Victorian villas “into models of white and modish minimalism.” The demolition of old London at the hands of big money—the banks and the City corporations—is, he says, worse than that wrought by Hitler’s blitzkrieg. “By comparison … the Führer was a conservationist.” Likewise, he denounces the privatization of institutions like the railroads, utilities, and even the probation service. “The notion that probation, which is intended to help and support those who have fallen foul of the law, should make a profit for shareholders seems beyond satire. … I never used to bother about capitalism. It was just a word. Not now.”

Bennett’s politics are a congenial and feisty mixture of “backward-looking radicalism and conservative socialism.” Contemptuous of what he sees as the “Torification” of British life, he finds that Britain has become “a state that gets away with doing as little as possible for its citizens and shuffling as many responsibilities as it can onto anyone who thinks they can make a profit out of them.”

The election of a Tory government on the day before his eighty-first birthday dismays him: “Now we have another decade of the self-interested and self-seeking, ready to sell off what’s left of our liberal institutions and loot the rest to their own advantage. It’s not a government of the nation but a government of half the nation, a true legacy of Mrs. Thatcher.” Of the former prime minister, whom he “detested,” he says that “no one [has]done such systematic damage to the North since William the Conqueror.”

As one might expect from someone in his ninth decade of life, Bennett also writes about aging. The diary frequently takes note of the death of friends. Of his own aches and pains (in one particular case, a bad ankle), he says: “I still have the absurd notion that, as with any other ailment, age and infirmity will run its course and I will recover from it. That there is no recovery—or only one—doesn’t always occur.”

In the introduction to his play The Habit of Art(2010), Bennett ruminates on the poets W. H. Auden and Philip Larkin, neither of whom, he says, was “much fun … at the finish.” For his own part, Bennett seems determined not to go that route as the end approaches. This volume, despite its doorstopper heft, is a great pleasure throughout, and often a lot of fun. In this era in American life when bombast, demagoguery, and bald-faced lying have shoved aside the old values of civility and honesty in public discourse, Bennett stands as a model of those virtues, along with intelligence, reasonableness, decency, humanity, aversion to cant, and a scrappy, no-nonsense irreverence for bullshit. On his eightieth birthday, his neighbor remarked, “It’s great that you can still piss people off however old you are.”

Philip Gambone, the author of four books, has been keeping a diary since 1968.