WE MAY HAVE canonized Oscar Wilde for his proto-gay life and martyrdom in late 19th-century England, but we tend to treat the very end of his life with either morbid fascination or awkward avoidance. Wilde’s premature death after serving his two-year jail sentence is somehow our own: an individual and collective gay failure. Our god died in his third year after prison instead of rising on the third day. It causes us to doubt our faith, if not in Wilde’s iconoclastic gospel, then in the hagiography of the modern LGBT movement. We don’t want Wilde to be a camp, tragic figure whose crucifixion and death are bathos, but rather a charismatic savior who died for our equality movement.

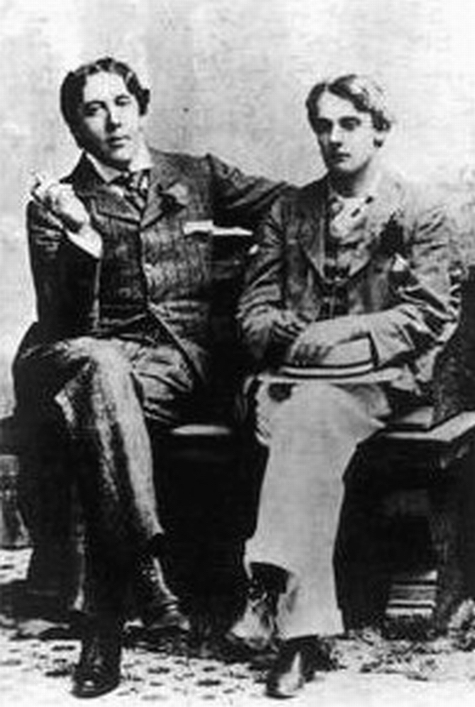

In Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years, Nicholas Frankel proposes that we consider Wilde’s final years outside of time, apart from what came before and what will follow. He also hopes that we will look at Wilde honestly in all his failings, and that we’ll respect his personal agency during that period rather than assume he was a broken man or Bosie’s plaything. Frankel’s Wilde is human, real, and didactic. The focus on Wilde the prisoner and lover humanizes him. Bosie Douglas, typically portrayed as Wilde’s Judas, comes closer to a beloved disciple in this version.

Frederick S. Roden teaches literature at the University of Connecticut. He edited a guide to Wilde studies for Palgrave Macmillan.