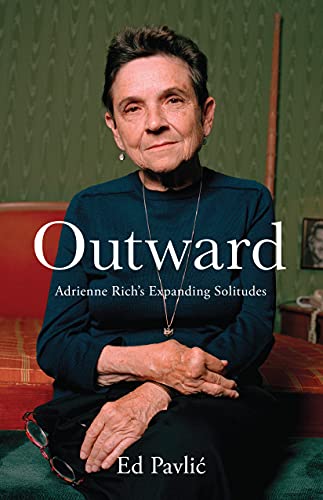

THE CALM, beautifully aged face of the poet Adrienne Rich gazes at the reader from the new book by her friend, Ed Pavlic, who explains that his relationship with Rich began when she (as a contest judge) chose his first book of poems for a prize, and they began exchanging letters in 2001.

Adrienne Rich (1929–2012) had a long and distinguished career as a poet and writer of nonfiction. Her early formalist poems of the 1950s seemed to fit the Zeitgeist of postwar American culture and of her own life as the wife of a Harvard economics professor and the mother of three sons. Her involvement in a variety of social justice movements in the ’60s was reflected in her poetry as well as her nonfiction, and she began moving in feminist and lesbian circles. In 1970, her husband committed suicide after she moved out of the home they had shared. In 1976, she began a relationship with Jamaican-born writer Michelle Cliff, which lasted until Rich’s death in 2012. Rich continued to write poetry and influential essays well into the 21st century.

Ed Pavlic acknowledges the long arc of Rich’s development as a writer who always engaged with current cultural trends and who never underestimated the difficulty of social change.

Ed Pavlic acknowledges the long arc of Rich’s development as a writer who always engaged with current cultural trends and who never underestimated the difficulty of social change.

Rich’s poetry is amply on display in this book. Pavlic quotes her work extensively while charting her search for independence from oppressive traditions in favor of a future of many possibilities, influenced by anti-sexist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist values. He discusses the seekers in her poetry—deep-sea divers, mountain-climbers, space explorers—as paradoxically self-driven but aware that their discoveries can only make sense to an audience or to fellow travelers. Pavlic traces the importance of communication, shared consciousness and evolving bodies of knowledge to Rich’s rejection of a white patriarchal cult of the individual.

The book is divided into five chapters that cover different phases of Rich’s writing career starting in 1951 and ending with her death in 2012. It’s hard to imagine a more thorough study of Rich’s work than this one. Pavlic acknowledges an impressive series of earlier critics who have tried to guide readers through her extensive œuvre.

A short poem titled “Delta” from Time’s Power (1987) is quoted in its entirety. It could serve as Rich’s response, from an afterlife, to Pavlic and all others who continue to analyze her words: “If you have taken this rubble for my past/ raking through it for fragments you could sell/ know that I long ago moved on/ deeper into the heart of the matter/ If you think you can grasp me, think again:/ my story flows in more than one direction/ a delta springing from the riverbed/ with its five fingers spread.”

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.