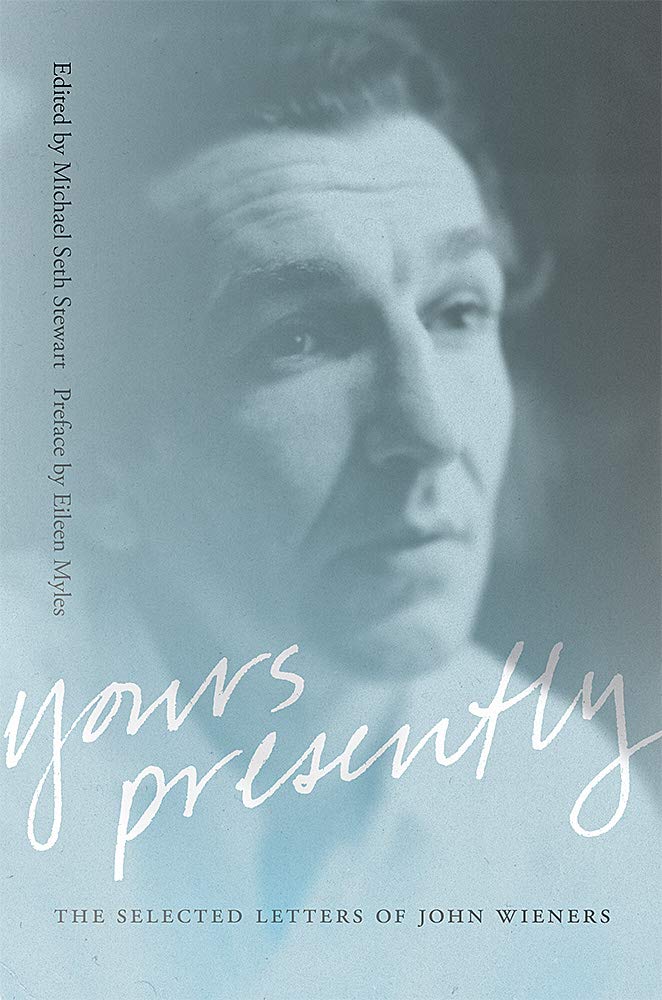

YOURS PRESENTLY

YOURS PRESENTLY

The Selected Letters of John Wieners

Edited by Michael Seth Stewart

University of New Mexico Press

333 pages, $75.

AT AGE 21, John Wieners (1934–2002) was high on poetry. The Black Mountain College student wrote to a friend in the spring of 1955, “I just know now that as long as I live I will be a poet, that my life, way of and function of, will be the writing of poetry, as long as it lasts.”

Wieners’ teacher Charles Olson had fueled his ambitions a few days earlier. During a writing class, the young man listened in stunned amazement as Olson lauded his poetry and the poet himself, in Wieners’ quotation of his teacher, for “possessing the talent to convert experience into form.” To top it off, Olson showed up at his room the next morning and “talked with me for two hours, talked not in the way that if you work hard you will be a poet someday, but that if you work hard you will be a better poet than you are now.” Wieners worshiped Olson, whose essay “Projective Verse” he considered a breakthrough in poetics. In the heady days of their early acquaintance, Wieners declared Olson to be “the only Man to have said anything new or fresh about Poetry—since before Pound.” The exacting, hard-drinking Olson would become his close friend and mentor.

The letters Wieners wrote from Black Mountain, located in western North Carolina, are among the most engaging in Yours Presently, showing him in his youth, an out gay man full of angst and ambition, revved up on art and raring to meet his destiny. Sadly, there would be much difficulty ahead, as he abused drugs in imitative pursuit of Rimbaud’s “derangement of the senses” and suffered recurring bouts of mental illness that landed him in one hospital after another.

He also began planning a new literary journal called Measure, a good idea that quickly became an obsession and a burden. The project, which resulted in three very interesting issues, put him in touch with poets of the Beat Movement, the San Francisco Renaissance, and the New York School—a gloriously gay Venn diagram of brash new talent. In a 1957 letter to Allen Ginsberg, requesting submissions, Wieners wanted the author of “America” to know: “There are other queer shoulders at the wheel, or well.”

In the fall of 1957, Wieners and Durkee moved from Boston to San Francisco. It was an exciting time and place for Wieners, with poets and pushers stumbling out of every alleyway. Wieners divided his time unwisely but still emerged, after breaking up with Durkee, as the author of The Hotel Wentley Poems (1958), a book that spackled, if it didn’t truly cement, his place in experimental American verse. He was 24 when Auerhahn Press published the book that editor Michael Seth Stewart calls “a slim collection of audaciously lyrical poems, teeming with startling images of the underground and buoyed by the exhilarating euphony he attributed, in a letter to Ginsberg, to the ‘magic of vowels.’” As a result of this well-received debut, Donald Allen included Wieners in The New American Poetry, 1945-1960, alongside Creeley, Duncan, John Ashbery, Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and Denise Levertov, among others. Despite his addictions and collapses, Wieners went on to publish Ace of Pentacles (1964), Pressed Wafer (1967), Asylum Poems (1969), and a number of other collections.

After returning to the East Coast, he spent time in various Massachusetts mental institutions and underwent punishing rounds of electric shock therapy. Before and after these harrowing experiences, he typically stayed at home in Milton with his parents. Clinging to his sanity by a thread, he lived in New York City in the early 1960s. With Olson’s sponsorship, he later studied and taught at SUNY–Buffalo. But he was a Bostonian at heart and lived there for his last thirty years, until his death at 68 in 2002.

With the exception of some distressingly paranoid letters to and about Creeley in 1968, Wieners comes across as a kind and intelligent man. Needy though he was, he maintained his dignity and championed the work of other innovative poets. He was an early promoter, for instance, of Edward Marshall, author of Leave the Word Alone, and broke ranks with most male poetry editors of his generation by seeking out women to contribute to Measure. Also of note, the poems he enclosed with many of his letters show how dedicated he was to his writing, even during hard times. A 1955 poem called “You Can’t Kill These Machines,” which was included in a letter to Michael Rumaker, exemplifies the beautiful oddness of his verse. It ends: “As long as my blood grows cold on the skin I love to/ and your good leg is on mine/ and a hundred feet up the ditch/ somebody else brushes off our mouths,/ who cares.”

Reading this volume, in letter after letter, you can feel Wieners tugging the pull cord of a knowledgeable, excitable mind. Sometimes the engine catches, other times it floods. Some readers may like that; I found it frustrating. I would have preferred a more stringent culling of letters and a biographical introduction much longer and more substantive than the five pages Stewart provides. But the oblique portrait that emerges from Yours Presently is still somehow arresting. Shaking off his demons, coming out of the fog of electric shock therapy, Wieners kept putting his queer shoulder back to the wheel of his chosen art form. He knew what he had to do.

Hilary Holladay is the author of The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography (2020).