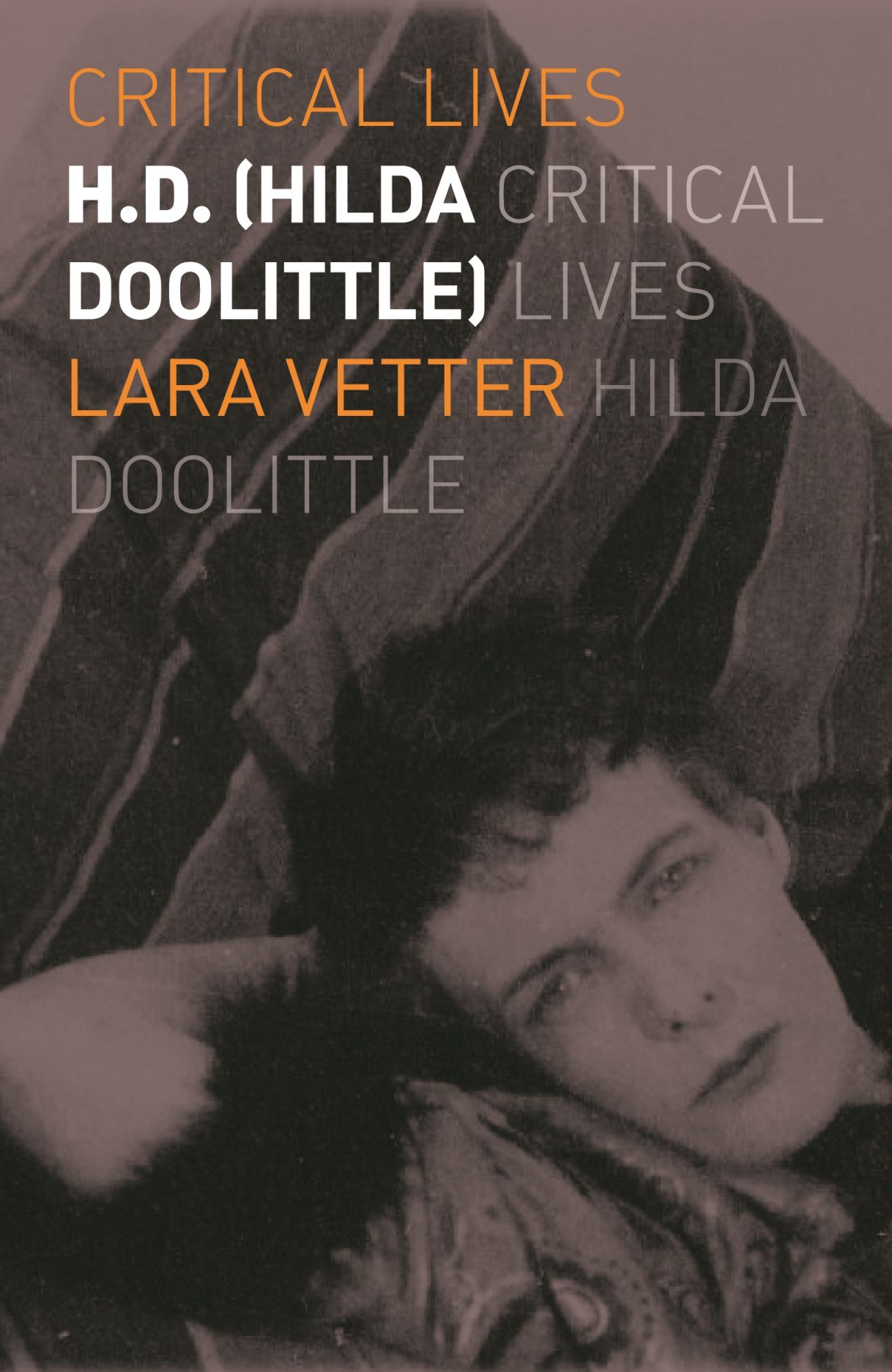

INNOVATIVE, bursting with creative energy, and accomplished in multiple genres, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle, 1886–1961) is a pivotal, if still under-appreciated, figure in literary modernism. Having christened herself “H.D., Imagiste” early in her career, she and her literary friends Ezra Pound (to whom she was briefly engaged), Richard Aldington (whom she married), and William Carlos Williams created Imagism, an early 20th-century movement popularizing brief, gemlike verses that dispensed with abstractions and conventional rhyme and meter. Over a period of fifty years, H.D. published poetry, short stories, novels, plays, essays, memoirs, and translations, edited film and literary journals, and both made and appeared in avant-garde films. Turning to her relationships, Freud called her “the perfect bi-,” and her lovers of both sexes justified his seemingly laudatory assessment.

In Lara Vetter’s engaging and well-paced H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), part of Reaktion Books’ series of concise biographies, the author admits early on that her subject presented some challenges:

At various points in her life, with various people, in various contexts, you will find a different H.D. She is tomboyish, assertive, confident, reclusive, shy and fearful. She is mercurial. She is detached and aloof, a loner. She is painfully vulnerable, always hiding from view. She is glamorous and charming, inviting attention. She shies away from social settings, stooping to minimize her presence and extravagant height. … She is always serious. She is funny, “saltily American, humorous, informal.” She had a laugh “like a waterfall, or a tinkling cascade of bells.”

Elsewhere, Vetter offers this pleasing juxtaposition: “She was extraordinarily well read—her library vast—but in stressful times, she binged on lesbian romances and police procedurals. For a time, she raised pet monkeys.” Such was the eclectic life of H.D., Imagiste.

Hilda Doolittle was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to Charles Doolittle, a math and astronomy professor at Lehigh University, and Helen Wolle Doolittle, a painter and musician. Charles Doolittle was a widower who brought two sons into the household. In addition to these half-siblings, Hilda had three brothers. She enjoyed a happy childhood and loved the natural beauty of her hometown, which was then a small rural Moravian community. When Hilda was eight, the family moved to Upper Darby, PA, so her father could teach at the University of Pennsylvania. Her life continued smoothly as she excelled in high school, studying Latin and the ancient Greeks, and got into Bryn Mawr College.

Adventurous and eager to launch her career as a writer, she left Bryn Mawr in the middle of her second year. After falling for a beautiful art student, Frances Gregg, and trying to make a life for herself in New York City, H.D. sailed for Europe in July of 1911 with Gregg and Gregg’s mother. The young lovers relished their adventures in France, which, Vetter writes, was “everything they had hoped for. The two snuck off to take nude photographs of one another on the beach, went to museums, and heatedly debated art and aesthetics, touring France with guidebooks firmly in hand.” Later on, in London, H.D. became part of a starry literary milieu, thanks to Pound’s introductions. In the ensuing decades, in both London and Paris, she would get to know T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway, Marianne Moore, Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas, among many others.

H.D. stayed on in London when Gregg returned to the U.S. After Gregg returned with a husband in tow, H.D. began a relationship with Richard Aldington, an English poet and critic who shared her intellectual and poetic interests, and married him in 1913. Vetter writes that for H.D. the marriage “would ultimately prove liberatory, shielding her sexual relationships with women and men in the decades to come.” The couple weathered a difficult spell when H.D. bore a stillborn daughter. While Aldington (who had his own extramarital affairs) was serving in the military during World War I, H.D. became pregnant by a Scottish composer, Cecil Gray. She named her baby girl Frances Perdita, combining her lesbian lover’s first name with that of a character in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, and stayed married to Aldington, though they finally divorced in 1938.

H.D. stayed on in London when Gregg returned to the U.S. After Gregg returned with a husband in tow, H.D. began a relationship with Richard Aldington, an English poet and critic who shared her intellectual and poetic interests, and married him in 1913. Vetter writes that for H.D. the marriage “would ultimately prove liberatory, shielding her sexual relationships with women and men in the decades to come.” The couple weathered a difficult spell when H.D. bore a stillborn daughter. While Aldington (who had his own extramarital affairs) was serving in the military during World War I, H.D. became pregnant by a Scottish composer, Cecil Gray. She named her baby girl Frances Perdita, combining her lesbian lover’s first name with that of a character in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, and stayed married to Aldington, though they finally divorced in 1938.

In time, she fell in love with another woman, Winifred “Bryher” Ellerman, a wealthy arts patron whom Vetter suggests would have identified as trans had she lived in a later era. Although Bryher married twice (the second time to a gay man), her heart was always with H.D. The two traveled together in Europe and cohabited much of the time, though H.D. required periods of solitary living so she could write at her leisure. Her daughter, who went by “Perdita,” grew up with two mothers, and her frank and humorous comments about H.D. and Bryher add interest to this biography. Bryher also wrote and published books and had an active life of her own, but H.D., with her silent-movie-star looks and her fame as a poet, was the center of attention and wanted it that way.

Given the space restrictions of a concise biography, Vetter does not go into great detail about H.D.’s writings, but we do get a sense of H.D. as a searching, intensely intellectual poet. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Vetter notes that H.D.’s poetry “is marked by truncated staccato lines, as she strives to achieve some semblance of ancient Greek rhythm in modern-day English. Sound is dominated by repetition and resonance, stressed syllables crowd into brief lines, and the effect is incantatory, as if she is summoning the gods.” Her lifelong devotion to the ancient Greeks, especially the plays of Euripides, revealed that H.D., like Pound and T.S. Eliot, became a modernist through her transfixed study of the distant past.

H.D. was everything all at once, and a trouper to boot. Of a bomb exploding terrifyingly close to her London home during the war, she said: “Must they make so much noise?” I enjoyed this book and recommend it to anyone interested in learning about a fascinating writer who really should be the subject of a film.

Hilary Holladay is the author of The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography.